by All Things Neonatal | Feb 15, 2017 | outcome, Uncategorized

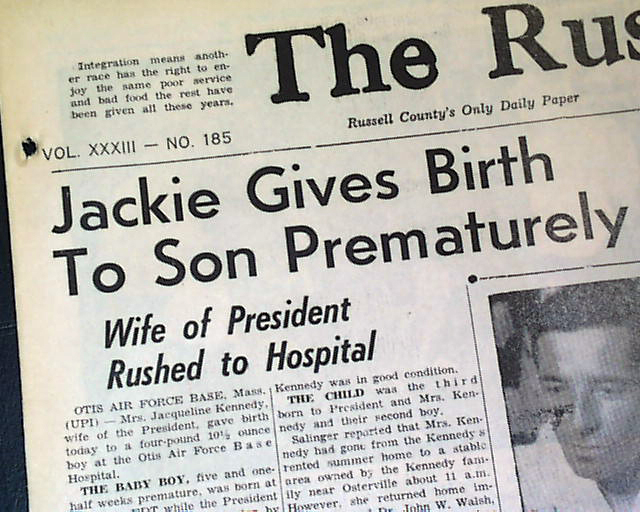

As a Neonatologist I doubt there are many topics discussed over coffee more than BPD. It is our metric by which we tend to judge our performance as a team and centre possibly more than any other. This shouldn’t be that surprising. The dawn of Neonatology was exemplified by the development of ventilators capable of allowing those with RDS to have a chance at survival.  As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.

As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.

The disease has changed to one where many factors such as oxygen and chorioamnionitis combine to cause arrest of alveolar development along with abnormal branching and thickening of the pulmonary vasculature to create insufficient air/blood interfaces +/- pulmonary hypertension. This new form is prevalent in units across the world and generally appears as hazy lungs minus the cystic change for the most part seen previously. Defining when to diagnose BPD has been a challenge. Is it oxygen at 28 days, 36 weeks PMA, x-ray compatible change or something else? The 2000 NIH workshop on this topic created a new approach to defining BPD which underwent validation towards predicting downstream pulmonary morbidity in follow-up in 2005. That was over a decade ago and the question is whether this remains relevant today.

Benchmarking

I don’t wish to make light of the need to track our rates of BPD but at times I have found myself asking “is this really important?” There are a number of reasons for saying this. A baby who comes off oxygen at 36 weeks and 1 day is classified as having BPD while the baby who comes off at 35 6/7 does not. Are they really that different? Is it BPD that is keeping our smallest babies in hospital these days? For the most part no. Even after they come off oxygen and other supports it is often the need to establish feeding or adequate weight prior to discharge that delays things these days. Given that many of our smallest infants also have apnea long past 36 weeks PMA we have all seen babies who are free of oxygen at 38 weeks who continue to have events that keep them in hospital. In short while we need to be careful to minimize lung injury and the consequences that may follow the same, does it matter if a baby comes off O2 at 36, 37 or 38 weeks if they aren’t being discharged due to apnea or feeding issues? It does matter for benchmarking purposes as one unit will use this marker to compare themselves against another in terms of performance. Is there something more though that we can hope to obtain?

When does BPD matter?

The real goal in preventing BPD or at least minimizing respiratory morbidity of any kind is to ensure that after discharge from the NICU we are sending out the healthiest babies we can into the community. Does a baby at 36 weeks and one day free of O2 and other support have a high risk of coming back to the hospital after discharge or might it be that those that are even older when they free of such treatments may be worse off after discharge. The longer it takes to come off support one would think, the more fragile you might be. This was the goal of an important study just published entitled Revisiting the Definition of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Effect of Changing Panoply of Respiratory Support for Preterm Neonates. This work is yet another contribution to the pool of knowledge from the Canadian Neonatal Network. In short this was a retrospective cohort study of 1503 babies born at <29 weeks GA who were assessed at 18-21 months of age. The outcomes were serious respiratory morbidity defined as one of:

(1) 3 or more rehospitalizations after NICU discharge owing to respiratory problems (infectious or noninfectious);

(2) having a tracheostomy

(3) using respiratory monitoring or support devices at home such as an apnea monitor

or pulse oximeter

(4) being on home oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure at the time of assessment

While neurosensory impairment being one of:

(1) moderate to severe cerebral palsy (Gross Motor Function Classification System ≥3)

(2) severe developmental delay (Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler

Development Third Edition [Bayley III] composite score <70 in either cognitive, language, or motor domains)

3) hearing aid or cochlear implant use

(4) bilateral severe visual impairment

What did they find?

The authors looked at 6 definitions of BPD and applied examined how predictive they were of these two outcomes. The combination of oxygen and/or respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA had the greatest capacity to predict this composite outcome. It was the secondary analysis though that peaked my interest. Once the authors identified the best predictor of adverse outcome they sought to examine the same combination of respiratory support and/oxygen at gestational ages from 34 -44 weeks PMA. The question here was whether the use of an arbitrary time point of 36 weeks is actually the best number to use when looking at these longer term outcomes. Great for benchmarking but is it great for predicting outcome?

It turns out the point in time with the greatest likelihood of predicting occurrence of serious respiratory morbidity is 40 weeks and not 36 weeks. Curiously, beyond 40 weeks it becomes less predictive. With respect to neurosensory impairment there is no real difference at any gestational age from 34-44 weeks PMA.

From the perspective of what we tell parents these results have some significance. If they are to be believed (and this is a very large sample) then the infant who remains on O2 at 37 weeks but is off by 38 or 39 weeks will likely fair better than the baby who remains on O2 or support at 40 weeks. It also means that the risk of neurosensory impairment is largely set in place if the infant born at < 29 weeks remains on O2 or support beyond 33 weeks. Should this surprise us? Maybe not. A baby who is on such support for over 5 weeks is sick and as a result the damage to the developing brain from O2 free radical damage and/or exposure to chorioamnionitis or sepsis is done.

It will be interesting to see how this study shapes the way we think about BPD. From a neurosensory standpoint striving to remove the need for support by 34 weeks may be a goal worth striving for. Failure to do so though may mean that we at least have some time to reduce the risk of serious respiratory morbidity after discharge.

Thank you to the CNN for putting out what I am sure will be a much discussed paper in the months to come.

by All Things Neonatal | Oct 19, 2016 | preemie, Uncategorized

This is a title that I hope caught your eye. In the nearly twenty years I have been in the field of Pediatrics the topic of parking being a barrier to parental visitation has come up again and again. A few years ago the concern about the cost of parking was so great that I was asked if I could find a pool of donors to purchase parking passes to offset the burden to the family. The theory of course is based on the idea that if parking were free in the NICU parents would visit more. If parents visit more they will be more involved in the care of their baby, more likely to breastfeed and with both of these situations in play the infant should be discharged earlier than other infants whose parents don’t visit. Try as I might it was a tough sell for donors who tend to prefer buying something more tangible that may bear their name or at least something they can look at and say “I bought that”. This is quite tough when it comes to a parking stall and as such I am still looking for that elusive donor. Having said that, is there any basis to believe that free parking is the solution that will deliver us from minimal visitation by some parents?

A Study May Help Answer The Question

Northrup TF et al published an article that was sent my way and to be honest I couldn’t wait to read it. A free parking trial to increase visitation and improve extremely low birth weight infant outcomes. This is like the holy grail of studies. A study that gets right to the point and attempts to answer the exact question I and others have been asking for some time. The study took place in Houston, Texas and was set up as an RCT in which families were randomized into two groups. Inclusion criteria were birth weight ⩽1000 g, age 7 to 14 days and deemed likely to survive. Seventy two patients were enrolled in the free parking group while 66 were placed in the usual care. Interestingly the power calculation determined that they would need 140 to show a difference so while 138 is close it wasn’t enough to truly show a difference but let’s see what they found.

The Results

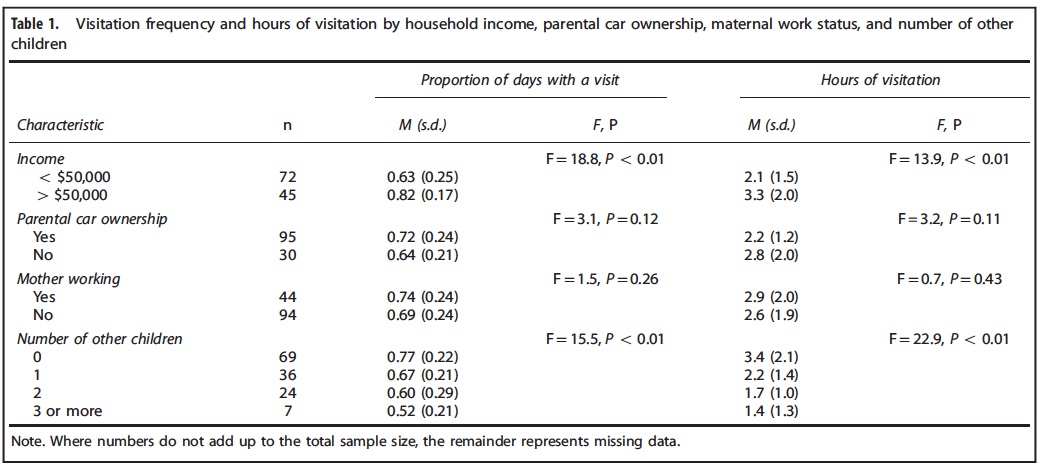

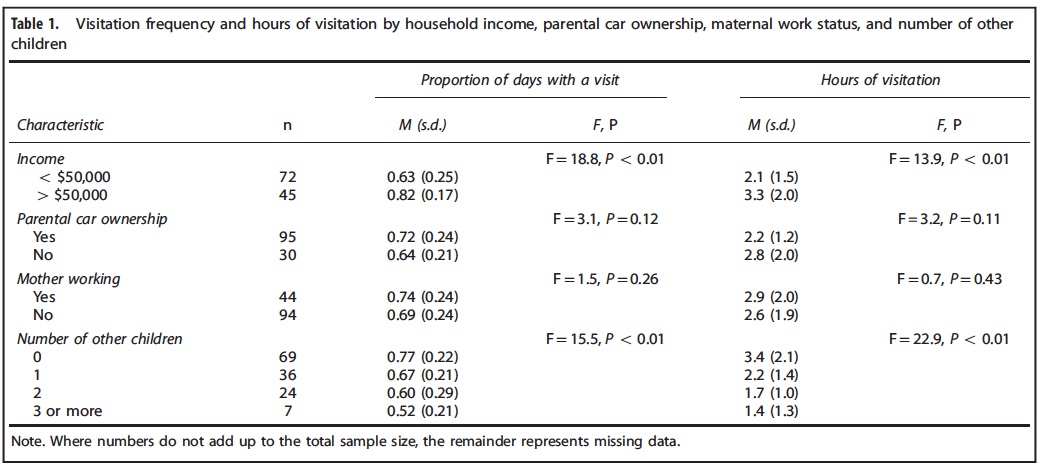

Free parking made absolutely no difference for the whole group. Specifically there was no difference in the primary outcome of length of stay or hours spent per visit. Some interesting information though that may not be that surprising was found to be of importance in the table below.

It may not seem like a surprise but the patients who were more affluent and those who had less children tended to visit more. The latter makes a lot of sense as what are many people to do when they have one or more other children to care for at home especially in the face of little support? Would free parking make one iota of difference if the barrier has nothing to do with the out of pocket cost?

The conclusion was that the strategy didn’t work that well but as you may have picked up I think the study was flawed. By applying the strategy to all they were perhaps affected by choosing the wrong inclusion criteria. Taken to an extreme, would a 50 million dollar Powerball winner care one bit about parking vouchers? It wouldn’t make any difference to whether they were going to come or not. Similarly a single mother with 5 other kids who lives below the poverty line and has little support is not going to come more frequently whether they have a voucher or not.

What if the study were redone?

I see a need to redo this study again but with different parameters. What if you randomized people with a car or access to one who lived below a certain income level and had a committed support person who could assure that team that they could care for any other children the family had when called upon? Or one could look at families with no other children and see if offering free parking led to more frequent visitation and then from there higher rates of Kangaroo Care and breastfeeding. I for one haven’t given up on the idea and while I was truly excited to be sent this article and sadly initially dismayed on first read, I am hopeful that this story has not seen it’s end.

It is intuitive to me that for some parents parking is a barrier to visiting. Finding the right population to prove this though is the key to providing the evidence to arm our teams with evidence to gain support from hospital administrations. Without it we truly face an uphill battle to get this type of support for families. Stay tuned…

by All Things Neonatal | Sep 2, 2016 | apnea of prematurity

Now that I have caught your attention it is only fair that I explain what I mean by such an absurd title. If you work with preterm infants, you have dealt with apnea of prematurity. If you have, then you also have had to manage such infants who seemingly are resistant to everything other than being ventilated. We have all seen them. Due to increasing events someone gives a load of methylxanthine and then starts maintenance. After a couple days a miniload is given and the dose increased with the cycle repeating itself until nCPAP or some other non-invasive modality is started. Finally, after admitting defeat due to persistent episodes of apnea and/or bradycardia, the patient is intubated. This, in the absence of some other cause for apnea such as sepsis or seizures is the methylxanthine resistant preterm infant. Seemingly no amount of treatment will amount to a reduction in events and then there is only so much that CPAP can do to help.

What Next?

Other strategies have been attempted to deal with such infants but sadly none have really stood the test of time. Breathing carbon dioxide might make sense as we humans tend to breathe quickly to excrete rising CO2 but in neonates while such a response occurs it does not last and is inferior to methylxanthine therapy. Doxapram was used in the past and continues to be used in Europe but concerns over impacts on neurodevelopment have been a barrier in North America for some time. Stimulating infants through a variety of methods has been tried but the downside to using for example a vibrating mattress is that sleep could be interfered with and there are no doubt impacts to the preterm infant of having weeks of disturbed sleep states on developmental outcomes.

What if we could make our preterm infants walk?

This of course isn’t physically practical but two researchers have explored this question by using vibration at proprioceptors in the hand and foot. Such stimulation may simulate limb movement and trick the brain into thinking that the infant is walking or running. Why would we do this?. It has been known for 40 years that movement of limbs as in walking triggers a respiratory stimulatory effect by increasing breathing. This has been shown in adults but not in infants but this possibility is the basis of a study carried out in California entitled Neuromodulation of Limb Propriceptive Afferents Decreases Apnea of Prematurity and Accompanying Intermittent Hypoxia and Bradycardia. This was a small pilot study enrolling 19 patients of which 15 had analyzable data. The design was that of alternating individual preterm infants born between 23 – 35 weeks to receive either vibratory stimulation or nothing and measuring the number and extent of apnea and bradycardia over these four periods. In essence this was a proof of concept study.

The stimulation is likened to that felt when a cell phone vibrates as this was the size of device used to generate the sensation.  The authors note that during the periods of stimulation the nurses noted no signs of any infant waking or seeming to be disturbed by the sensation. The results were quite interesting especially when noting that 80% of the infants were on caffeine during the time of the study so these were mostly babies already receiving some degree of stimulation

The authors note that during the periods of stimulation the nurses noted no signs of any infant waking or seeming to be disturbed by the sensation. The results were quite interesting especially when noting that 80% of the infants were on caffeine during the time of the study so these were mostly babies already receiving some degree of stimulation

Should we run out and buy these?

The stimulation does appear to work but with any small study we need to be careful in saying with confidence that this would work in a much larger sample. Could there have been some other factor affecting the results? Absolutely but the results nonetheless do raise an eyebrow. One thing missing from the study that I hope would be done in a larger sample next time is an EEG. The authors are speculating that by placing the vibration over the hand and foot the brain is perceiving the signal as limb movement but it would have been nice to see the motor areas of the brain “lighting up” during such stimulation. As we don’t have that I am left wondering if the vibration was simply a form of mild noxious stimulus that led to these results. Of course in the end maybe it doesn’t matter if the results show improvement but an EEG could also inform us about the quality of sleep rather than relying on nursing report of how they thought the baby tolerated the stimulus. I know our nursing colleagues are phenomenal but can they really discern between quiet and active sleep cycles? Maybe some but I would guess most not. There will also be the naysayers out there that will question safety. While we may not perceive a gentle vibration as being harmful, with such a small number of patients can we say that with certainty? I am on the side of believing it is probably insignificant but then again I tend to see the world through rose coloured glasses.

Regardless of the filter through which you view this world of ours I have to say I am quite excited to see where this goes. Now we just have to figure out how to manage the “real estate” of our infant’s skin as we keep adding more and more probes that need a hand or a foot for placement!

by All Things Neonatal | Aug 18, 2016 | quality improvement, Uncategorized

The giant leaps in Neonatology may for the most part be over. So many outstanding research trials have brought us to where we are today. The major innovations of surfactant replacement, the discovery of nitric oxide and its later use to treat pulmonary hypertension, caffeine for apnea have all changed our field for the better. Cooling for HIE has certainly changed my practice in that I now truly have no idea what to tell parents after even some of the worst cases of asphyxia as our team has witnessed “miracles”after cooling. What will come next? My bet is that we are about to enter the era of Quality Improvement more and more. Think about the last study you read that had a major change in your practice or better yet made a substantial change in survival or neurodevelopmental outcome.

Tweaking care is where its at.

I like to think of it as fine tuning.  As the era of the major leaps in care seems to be passing us by what I see more and more are studies looking at how to make further improvements on what we already know. In some cases such as using higher doses of caffeine may reduce the incidence of apnea further compared to standard dosing while cooling for 96 hours instead of 72 and at lower temperatures after asphyxia may not be such a good idea after all. There will be some studies that suggest a modification of practice and then others that suggest we should look elsewhere for further improvements. With all of this evidence coming out in hundreds if not thousands of journals every week it is difficult to keep up and it may be that our focus is in need of a change in direction or at least devoting members of the team to look at something different.

As the era of the major leaps in care seems to be passing us by what I see more and more are studies looking at how to make further improvements on what we already know. In some cases such as using higher doses of caffeine may reduce the incidence of apnea further compared to standard dosing while cooling for 96 hours instead of 72 and at lower temperatures after asphyxia may not be such a good idea after all. There will be some studies that suggest a modification of practice and then others that suggest we should look elsewhere for further improvements. With all of this evidence coming out in hundreds if not thousands of journals every week it is difficult to keep up and it may be that our focus is in need of a change in direction or at least devoting members of the team to look at something different.

That Focus Is On Quality Improvement (QI)

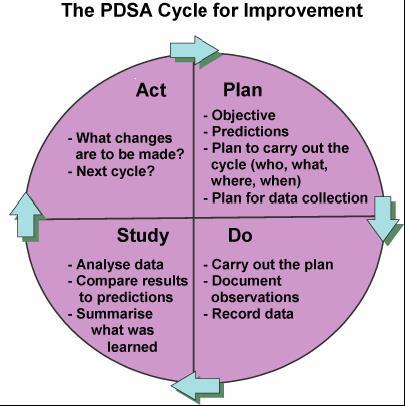

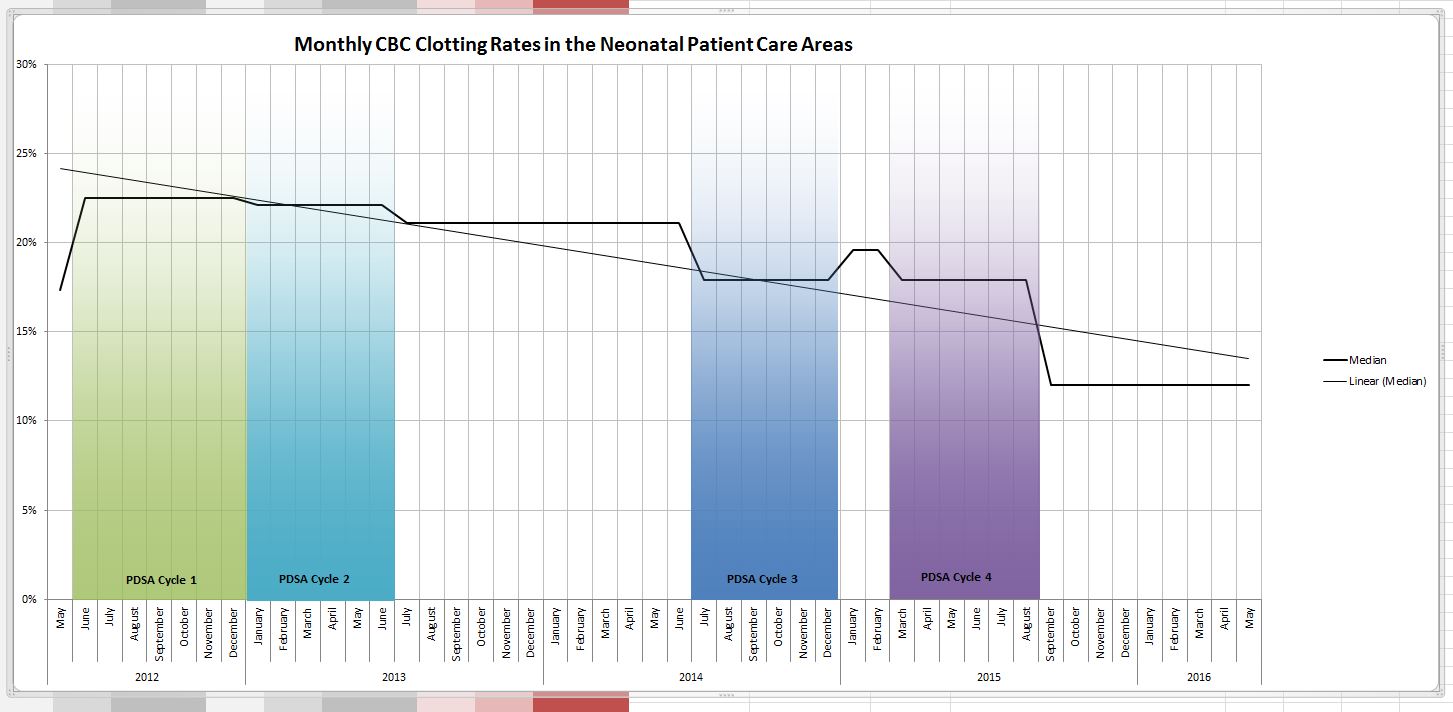

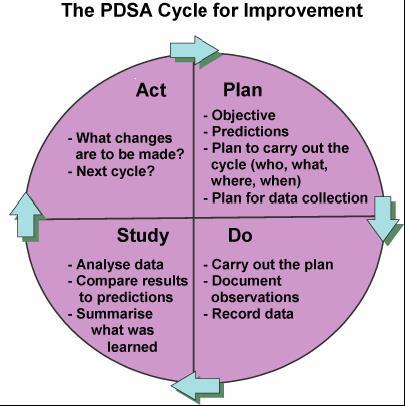

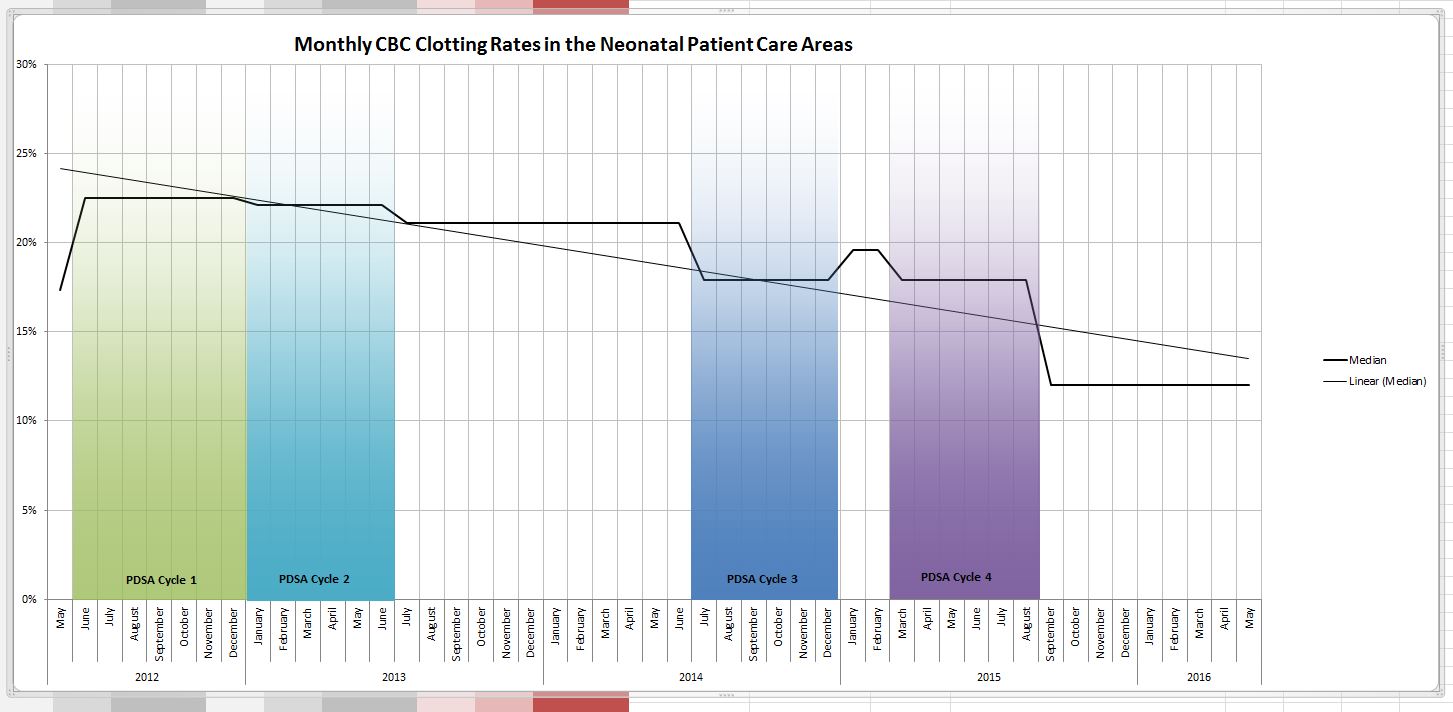

Before I go on I don’t want to insinuate that I am something that I am not. I do not have any formal training in QI and consider myself an amateur but I do understand enough to undertake a PDSA cycle and see where it takes me.  To me QI is about finding ways to actually make your best practices the best they can be. Take for example our units goal to minimize needle pokes by carefully examining the usefulness of common tests that we perform. Add to this the recent implementation of non invasive technology such as transcutaneous bilirubin metres which our evidence suggests can reliably replace a serum sample to screen for those in need of phototherapy. While I commonly like to praise our team for its ability to critically think about needed bloodwork it was only through the collection of data using audit tools that we discovered we had a problem. The problem was that the rate of CBC samples that were clotting were unacceptably high at over 30%. This was compared to another NICU in the same city that had a rate of less than 1/3 that. The initial reaction since it was trained lab personnel collecting at the low clotting site vs nursing at the high rate site was that the solution was simple. Just change back to lab personnel (as it used to be) at the high rate site! Ah but that would create another problem. Other evidence used to build a care plan for our preterm infants suggested that clustering of care was better for them than poking them at the usual run time of the lab techs so we had a conflict. How did we solve it? We resisted our urge for the quick fix and entered into a formal QI project.

To me QI is about finding ways to actually make your best practices the best they can be. Take for example our units goal to minimize needle pokes by carefully examining the usefulness of common tests that we perform. Add to this the recent implementation of non invasive technology such as transcutaneous bilirubin metres which our evidence suggests can reliably replace a serum sample to screen for those in need of phototherapy. While I commonly like to praise our team for its ability to critically think about needed bloodwork it was only through the collection of data using audit tools that we discovered we had a problem. The problem was that the rate of CBC samples that were clotting were unacceptably high at over 30%. This was compared to another NICU in the same city that had a rate of less than 1/3 that. The initial reaction since it was trained lab personnel collecting at the low clotting site vs nursing at the high rate site was that the solution was simple. Just change back to lab personnel (as it used to be) at the high rate site! Ah but that would create another problem. Other evidence used to build a care plan for our preterm infants suggested that clustering of care was better for them than poking them at the usual run time of the lab techs so we had a conflict. How did we solve it? We resisted our urge for the quick fix and entered into a formal QI project.

How did we do it and what were the results?

It took us four rounds of PDSA cycles but in the end we found a solution that has lasted. As I write this I learned that one of our two units that had the high rates set a record low this past month of a 4.9% clotting rate even lower than the comparative site that began with a low clotting rate. It took work and was by no means easy but the dedication of our nurse educator to the task made all the difference. Fortunately, for those who don’t know where to begin an incredible resource is available from BMJ Quality Improvement who provide a step by step process to carry out your project. Moreover after using their template for publishing such work, we were able to publish our work which we hope may be of help for other centres that find themselves in a similar situation. Perhaps the solution might be the same or at least similar enough to try one of our interventions? The full paper can be found at the end of the post but the trend over time is so impressive that I felt obliged to show you the results.

Why should you care?

Teams spend so much time rolling out new evidence based initiatives. All the evidence in world won’t help if the intervention isn’t achieving the results you expect. How will you know unless you audit your results? You may be surprised to find that what you expected in terms of benefit you aren’t seeing. By applying the principals of QI you may find you don’t need to look for another treatment or device but rather you simply need to change your current practice.  A little education and direction may be all that is needed. You may also find to your surprise that what you thought everyone was doing is not what they are doing at all.

A little education and direction may be all that is needed. You may also find to your surprise that what you thought everyone was doing is not what they are doing at all.

Resist the quick solution and put in the time to find the right solution. As Carl Honore suggests slowing things down may be the best thing for all of us and more importantly the patients we care for.

Link to the full article:

References

- Mohammed S et al. High versus low-dose caffeine for apnea of prematurity: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pediatr 2015 Jul;174(7):949-56.

- Shankaran S et al. Effect of depth and duration of cooling on deaths in the NICU among neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: a randomized clinical trial.JAMA 2014 Dec 24-31;312(24):2629-39

by All Things Neonatal | Jun 15, 2016 | Uncategorized, ventilation

As the saying goes the devil is in the details. For some years now many centres worldwide have been publishing trials pertaining to high flow nasal cannulae (HFNC) particularly as a weaning strategy for extubation. The appeal is no doubt partly in the simplicity of the system and the perception that it is less invasive than CPAP. Add to this that many centres have found less nasal breakdown with the implementation of HFNC as standard care and you can see where the popularity for this device has come from.

This year a contact of mine Dominic Wilkinson on twitter (if you don’t follow him I would advise having a look!) published the following cochrane review, High flow nasal cannula for respiratory support in preterm infants. The review as with most cochrane systematic reviews is complete and comes to a variety of important conclusions based on 6 studies including 934 infants comparing use of HFNC to CPAP.

1. No differences in the primary outcomes of death (typical RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.36; 5 studies, 896 infants) or CLD.

2. After extubation to HFNC no difference in the rate of treatment failure (typical RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.55; 5 studies, 786 infants) or reintubation (typical RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.20; 6 studies, 934 infants).

3. Infants randomised to HFNC had reduced nasal trauma (typical RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.79; typical risk difference (RD) -0.14, 95% CI -0.20 to -0.08; 4 studies, 645 infants).

4. Small reduction in the rate of pneumothorax (typical RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.06; typical RD -0.02, 95% CI -0.03 to -0.00; 5 studies 896 infants) in infants treated with HFNC but the RR crosses one so this may be a trend at best.

If one was to do a quick search for the evidence and found this review with these findings it would be very tempting to jump on the bandwagon. Looking at the review a little closer though there is one line that I hope many do not miss and I was happy to see Dominic include it.

“Subgroup analysis found no difference in the rate of the primary outcomes between HFNC and CPAP in preterm infants in different gestational age subgroups, though there were only small numbers of extremely preterm and late preterm infants.”

In his conclusion he further states:

Further evidence is also required for evaluating the safety and efficacy of HFNC in extremely preterm and mildly preterm subgroups, and for comparing different HFNC devices.

With so few ELBW infants included and with these infants being at highest risk of mortality and BPD our centre has been reluctant to adopt this mode of respiratory support in the absence of solid evidence that it is equally effective to CPAP in these smallest infants. A big thank you to our Respiratory Therapy Clinical Specialist for harping on this point over the years as the temptation to adopt has been strong as other centres turn to this strategy.

Might Not Be So Safe After All

Now do not take what I am about to say as a slight against my twitter friend. The evidence to date points to exactly what he and his other coauthors concluded but with the release of an important paper in May by Taka DK et al, I believe caution is needed when it comes to our ELBW infants.

High Flow Nasal Cannula Use Is Associated with Increased Morbidity and Length of Hospitalization in Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants

This paper adds to the body of literature on the topic as it truly focuses on the outcome of infants < 1000g. While this study is retrospective in nature it does cover a five year period and examines important outcomes of interest to this population.

The primary outcome in this case was death or BPD and whether HFNC was used alone or with CPAP, this was more frequent than when CPAP was used alone. Other important findings were the need for multiple and longer courses of ventilation in those who received at least some HFNC. In these times of overburdened health care systems with goals of improving patient flow, it is also worth noting that there was a significant prolongation of length of stay with use of HFNC or HFNC and CPAP.

One interesting observation was that the group that fared the worst across the board was the combination of CPAP and HFNC rather than HFNC alone.

|

CPAP (941) |

HFNC (333) |

HFNC +/- CPAP (1546) |

| CPAP d (median, IQR) |

15(5-28) |

|

7 (1-19) |

| HFNC d (median, IQR) |

14(5-25) |

13 (6-23) |

| HFNC +/- CPAP |

15 (5-28) |

14(5-25) |

26 (14-39) |

| BPD or death % |

50.40% |

56.80% |

61.50% |

| BPD % |

42.20% |

52.20% |

59.00% |

| Multiple ventiation courses |

51.10% |

53.10% |

64.70% |

| More than 3 vent courses |

17.60% |

21.00% |

29.40% |

| Ventilator d (median, IQR) |

18(5-42) |

25 (6-52) |

30 (10-58) |

I believe the finding may be explained by the problem inherent with retrospective studies. This is not a study in which patients were randomized to either CPAP, HFNC or CPAP w/HFNC. If that were the case one would expect lung pathologies and severity of illness to even ou,t such that differences between groups might be explained by the difference in treatments. In this study though we are looking though the rearview mirror so to speak. How could we account for the combination being worse than the HFNC alone? I suspect it relates to the severity of lung disease. The babies who were placed on HFNC and did well on it might have had less severe chronic changes. What might be said about those that had the combination? Well, one could postulate that there might be some who were extubated to HFNC and collapsed needing escalation to CPAP and then failing that therapy were reintubated. Another explanation could be those babies who were placed on CPAP after extubation and transitioned before their lungs were ready to HFNC may have failed and lost FRC thereby going back to CPAP and possibly intubation. Exposure in either circumstance to HFNC would therefore put them at risk of further positive pressure ventilation and subsequent further lung injury. The babies who could tolerate transition to HFNC without CPAP might be intermediary in their outcomes (as they were found to be) as they lost FRC but were able to tolerate it but consumed more calories leaving less for growth and repair of damaged tissue leading to prolonged need for support.

Either way, the use of HFNC was found to lead to worse outcomes and in the ELBW infant should be avoided as routine practice pending the results of a prospective RCT on the subject.

Is it a total ban though?

As with many treatments that one should not consider standard of care there may be some situations where there may be benefit. The ELBW infant with nasal breakdown from CPAP that despite excellent nursing and RRT attention continues to demonstrate tissue damage is one patient that could be considered. The cosmetic implications and potential for surgical correction at a later date would be one reason to consider a trial of HFNC but only in the patient that was close to being able to come off CPAP. In the end I believe that if a ELBW infant needs non invasive pressure support then it should be with CPAP but as there saying goes there may be a right time and a place for even this modality.

As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.

As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.

The authors note that during the periods of stimulation the nurses noted no signs of any infant waking or seeming to be disturbed by the sensation. The results were quite interesting especially when noting that 80% of the infants were on caffeine during the time of the study so these were mostly babies already receiving some degree of stimulation

The authors note that during the periods of stimulation the nurses noted no signs of any infant waking or seeming to be disturbed by the sensation. The results were quite interesting especially when noting that 80% of the infants were on caffeine during the time of the study so these were mostly babies already receiving some degree of stimulation

As the era of the major leaps in care seems to be passing us by what I see more and more are studies looking at how to make further improvements on what we already know. In some cases such as using

As the era of the major leaps in care seems to be passing us by what I see more and more are studies looking at how to make further improvements on what we already know. In some cases such as using  To me QI is about finding ways to actually make your best practices the best they can be. Take for example our units goal to minimize needle pokes by carefully examining the usefulness of common tests that we perform. Add to this the recent implementation of non invasive technology such as transcutaneous bilirubin metres which our evidence suggests can reliably replace a serum sample to screen for those in need of phototherapy. While I commonly like to praise our team for its ability to critically think about needed bloodwork it was only through the collection of data using audit tools that we discovered we had a problem. The problem was that the rate of CBC samples that were clotting were unacceptably high at over 30%. This was compared to another NICU in the same city that had a rate of less than 1/3 that. The initial reaction since it was trained lab personnel collecting at the low clotting site vs nursing at the high rate site was that the solution was simple. Just change back to lab personnel (as it used to be) at the high rate site! Ah but that would create another problem. Other evidence used to build a care plan for our preterm infants suggested that clustering of care was better for them than poking them at the usual run time of the lab techs so we had a conflict. How did we solve it? We resisted our urge for the quick fix and entered into a formal QI project.

To me QI is about finding ways to actually make your best practices the best they can be. Take for example our units goal to minimize needle pokes by carefully examining the usefulness of common tests that we perform. Add to this the recent implementation of non invasive technology such as transcutaneous bilirubin metres which our evidence suggests can reliably replace a serum sample to screen for those in need of phototherapy. While I commonly like to praise our team for its ability to critically think about needed bloodwork it was only through the collection of data using audit tools that we discovered we had a problem. The problem was that the rate of CBC samples that were clotting were unacceptably high at over 30%. This was compared to another NICU in the same city that had a rate of less than 1/3 that. The initial reaction since it was trained lab personnel collecting at the low clotting site vs nursing at the high rate site was that the solution was simple. Just change back to lab personnel (as it used to be) at the high rate site! Ah but that would create another problem. Other evidence used to build a care plan for our preterm infants suggested that clustering of care was better for them than poking them at the usual run time of the lab techs so we had a conflict. How did we solve it? We resisted our urge for the quick fix and entered into a formal QI project.

A little education and direction may be all that is needed. You may also find to your surprise that what you thought everyone was doing is not what they are doing at all.

A little education and direction may be all that is needed. You may also find to your surprise that what you thought everyone was doing is not what they are doing at all.