by All Things Neonatal | Mar 31, 2016 | ID, Infection, Neonatal, Uncategorized

I have been a huge advocate of RSV prophylaxis since my days as a Pediatric resident. When I started my residency we were not using Palivizumab (Synagis) and I recall admitting 10+ patients per day at times with bronchiolitis. With the use of passive immunization this rate dropped dramatically in Manitoba although rates in other areas of the country may have not seen such significant impacts. Manitoba may be somewhat different from many areas due to the communities in Nunavut being so impacted when RSV enters these areas and can infect many of the children due to crowded living conditions and inability to really isolate kids from one and other. The lack of benefit in other areas though, has no doubt led to controversy among practitioners who often wonder if giving 5 IM injections during the RSV season is indeed worth it. The real question has not necessarily been does it work but to whom should it be given so that you get the most benefit.

A Big Change in The Last Year

In 2015 the CPS published a revised statement entitled Preventing hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus infection. This statement has caused a great deal of controversy at least among those I have spoken with due to its significant departure from the previous recommendations. As per the statement:

- In preterm infants without CLD born before 30 + 0 weeks’ GA who are <6 months of age at the start of RSV season, it is reasonable (but not essential) to offer palivizumab. Infants born after 30 + 0 weeks’ GA have RSV admission rates that are consistently ≤7% (Figure 3), yielding a minimum number needed to treat of 18 (90 doses of palivizumab to prevent one RSV admission) if one assumes 80% efficacy and five doses per infant. Therefore, palivizumab should not be prescribed for this group.

Gone are recommendations for treating those from 30 – 32 weeks and moreover 33- 35 weeks if meeting certain conditions. There is a provision for those in Northern communities to expand these criteria to 36 0/7 weeks if such infants would require medical transport to receive care for bronchiolitis. What is not really clear though is what is meant by Northern communities in terms of criteria to determine suitability exactly. Incidentally, the criteria are not so different than the AAP statement from August 2014.

Do We Need So Many Shots?

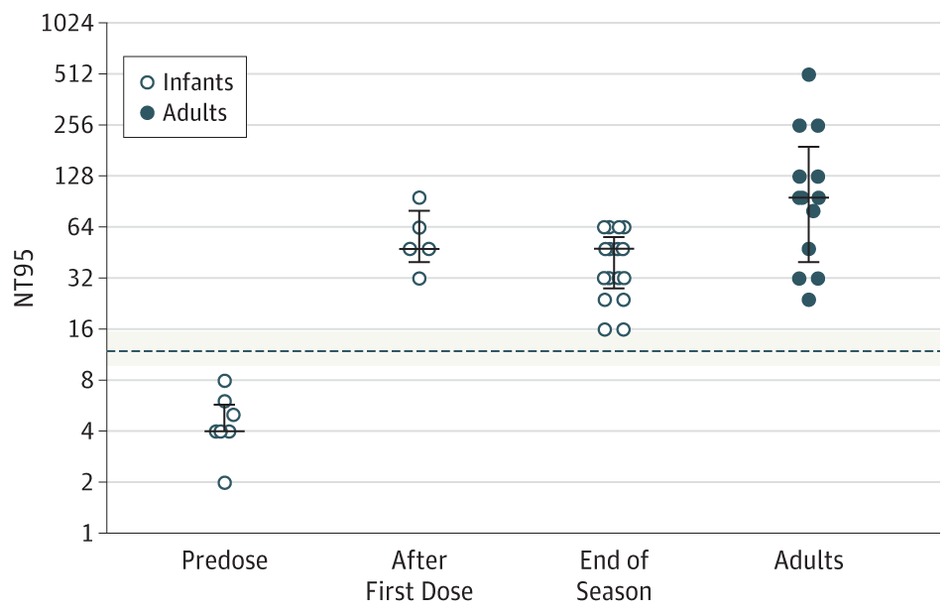

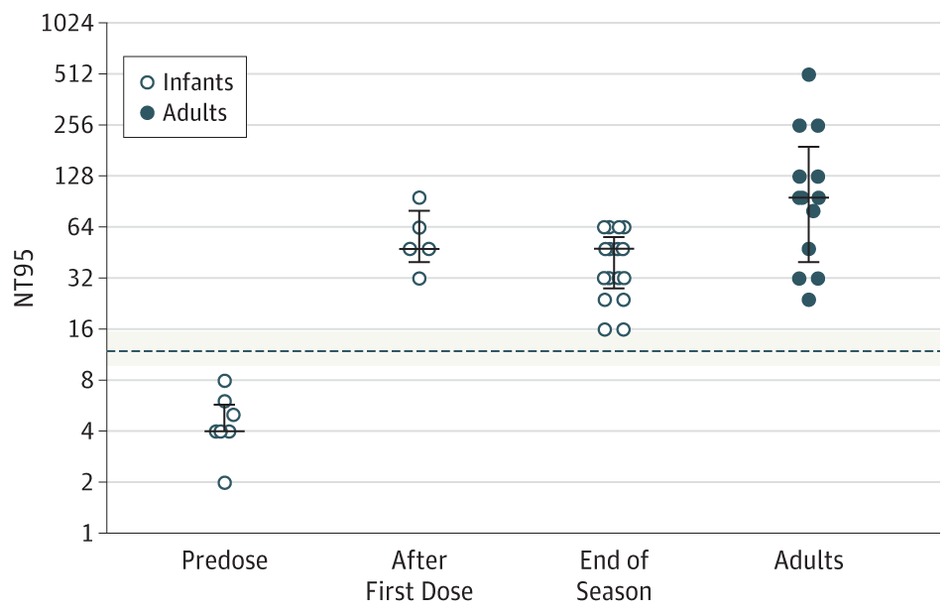

Just at the end of 2016 though Lavoie P et al in Vancouver, BC published a letter outlining their experience with a modified schedule of either 3 or 4 doses of palivizumab during the RSV season. Included in the letter are their criteria for determining the number of doses and importantly pharmacokinetic data demonstrating the effectiveness of such schedules in achieving protective titres.  The 3 dose schedule was used for those infants born between 29 0/7 and 35 weeks gestational age who had a risk factor score of 42 or more. Interestingly at the end of the RSV season, depriving such infants of 1 or 2 doses did not appear to impair the ability of the infant to maintain protective levels.

The 3 dose schedule was used for those infants born between 29 0/7 and 35 weeks gestational age who had a risk factor score of 42 or more. Interestingly at the end of the RSV season, depriving such infants of 1 or 2 doses did not appear to impair the ability of the infant to maintain protective levels.

From a clinical standpoint the outcome data during this period examining 514 (3 dose) and 666 (4 dose) patients similarly suggests that they were indeed protected from disease. In the 3 dose cohort only 1 patient was hospitalized with RSV during the dosing period and 1 infant afterwards. In the 4 dose group, 10 were hospitalized with RSV during the dosing schedule and a set of twins afterwards. Aside from these known RSV infections, an additional 7 and 18 patients were hospitalized with bronchiolitis without viral identification during the dosing schedule with no cases of bronchiolitis afterwards. Taken altogether and assuming that all cases were indeed RSV bronchiolitis the authors conclude that the overall rates are no different than those seen with a 5 dose schedule.

Is Something Rotten In The State of Denmark?

There is something peculiar here though. There is no doubt that palivizumab must have gone through rigorous pharmacokinetic testing in order to determine the correct number of doses needed. For a 3-4 dose regimen to provide the same coverage in terms of antibody titres seems strange to me. I would love to believe the data but there is a skeptic in me. Secondly with respect to counting hospital admissions is this exhaustive in terms of including all hospitalization a in BC or at only some sites? Clarity is needed before considering such changes to practice. Strangely it has been several months since this experience was published and there has been no discussion of it at least locally.* Something as dramatic as this should have sparked some discussion and the absence of such leaves me questioning what am I missing?

From the standpoint of reducing interventions and pain in the neonate I am intrigued by these findings. Parents as well would no doubt be happier with 3-4 IM injections over 5. The additional benefit is no doubt financial as this product while effective does carry a significant cost per dose. As you can see I have my doubts about the reproducibility of the results but it does at least offer some centres that have not been as enthusiastic about palivizumab something to consider. For some, the BC approach just might be the right thing.

- I indicate that there has been little discussion locally of the article discussed. There has indeed been discussion both here and in other Canadian provinces. What I meant by that comment is that among my colleagues in Neonatology and Infectious Diseases and housestaff I have had only one discussion.

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 26, 2016 | transplantation, Uncategorized

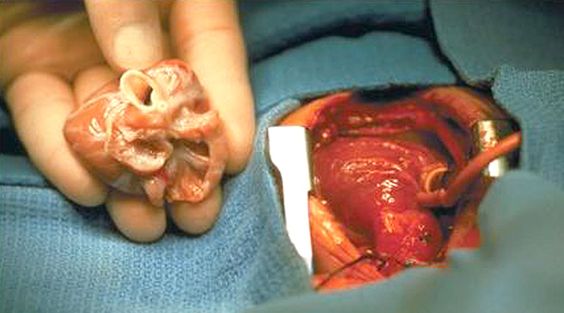

It seems fitting that I would be writing this on the Easter holiday with the symbolism of death followed by resurrection being the principal path for an organ to live on in another after departing their host. This topic came across my radar this week after I caught the following article on NBC news that I would encourage you to take a look at as it really captures the state of this practice in the US at the moment.

The Littlest Donors:Neonatal Organ Donation Offers Hope in Tragedy

This may surprise you but there really is nothing in the literature about this. There was a flurry of articles about neonatal transplantation in the late 1980s as debate raged about the ethics of using anencephalic newborns as donors but since then very little. I could find one article in pubmed which is a basic science article showing that mid trimester fetuses lung tissue can be used to regenerate cells in a recipient lung scaffold many hours after the stillbirth had occurred with the longest duration being 41 hours in this study. It would seem based on this study that the capacity for stillborn tissue to survive outside the deceased in theory then could provide a window for obtaining consent although how long such whole organs would last is uncertain.

The Big Questions?

How as a medical society we could manage this is a challenging one. Consent would only be possible after the recognition of fetal loss and who knows how long a window there would be from the time of death until the baby was delivered. Approaching families to ask about organ donation after they have just suffered a fetal loss is a difficult task to say the least. On the other hand the opportunity for some families to have some good come out of their tragedy as the NBC article points out may be therapeutic in some way.

Lastly, there is no question that there is a need for small organs. Having worked previously in a centre that offered cardiac transplantation I recall waiting for available hearts that never came or came too late. The challenge is that the thorax is only so big in a newborn and can’t accommodate a heart from a child or adult. Add to this that certain conditions preclude a baby or child from donating depending on the cause of death and having access to a larger pool of potential organs could indeed change the landscape of organ transplantation.

I should also stress that I am not talking about Planned Parenthood who has been accused of selling aborted fetuses tissue (having said that I can find little hard evidence for these claims out there). These are all babies who have been stillborn and not intentionally born to harvest organs.

I doubt this is the last you will hear of this but as the topic becomes more mainstream I can see ethicists and legal teams coming to the forefront to tackle this at each hospital and across many countries. It will be intriguing to follow this story and see how it unfolds.

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 17, 2016 | antibiotics, MAS, Uncategorized

We live in a world at the moment where the public has become increasingly aware of the dangers of antibiotic overuse. Parents are more than ever requesting no erythromycin for the eyes after birth, and even on occasion questioning the need for antibiotics after delivery for the infant with risk factors for sepsis. The media has latched on to the debate as well by publishing the sensational articles about superbugs and medicine running out of the last lines of defence such as this article from the CBC.

As teams caring for newborns both preterm and term we are also increasingly aware of the dangers of altering the microbiome of these vulnerable infants with antibiotic overuse. Some babies robbed of the vaginal microbiome when delivery occurs by C-section, have their parents swabbing their newborn with vaginal secretions to populate their child with the “good bacteria” that come through a “natural” delivery although recent commentary questions the safety of such practice.

Infants born through meconium stained amniotic fluid can certainly become sick after delivery. Inhalation of meconium in the sickest infants often occurs during gasping episodes in utero after hypoxic stress causes evacuation of the rectal contents. The fetuses who inhale this material may go on to develop, inflammatory changes, areas of atelectasis and hyperinflation and pulmonary hypertension; the so called meconium aspiration syndrome. These infants of course may be extremely sick and need high frequency ventilation to manage their CO2 retention and in some cases may go on to ECMO although with inhaled nitric oxide this has become less common. As another consideration, could infection such as chorioamnionitis be the inciting event to cause passage of meconium in utero?

The health care team though for as long as I have been in practice would add to the treatment plan a course of antibiotics. In fact I would guess that many Neonatologists the world over have uttered the phrase “They are REALLY sick, please start antibiotics”. The real question though is whether the baby is in fact infected. Meconium is certainly a good growth medium for bacteria but with the short time from passage to delivery in most cases I doubt there is much time for significant growth. Moreover, I have found myself saying many times that such infants have a chemical pneumonitis and have often questioned whether antibiotics are really needed. Nonetheless it would take nerves of steel in some cases to not use antibiotics in these patients.

Then along came this study

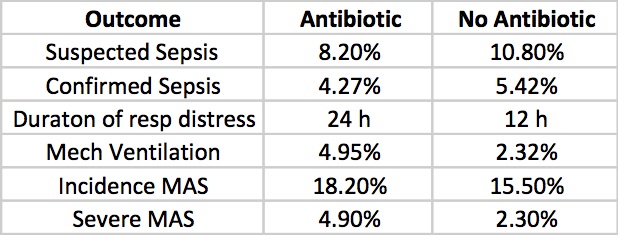

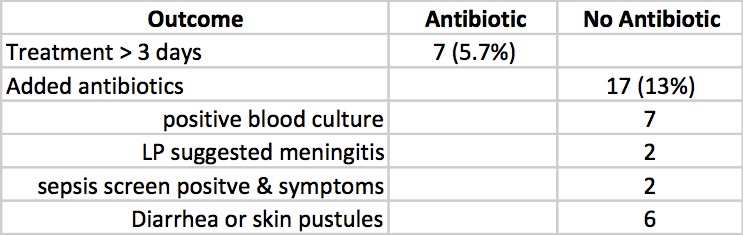

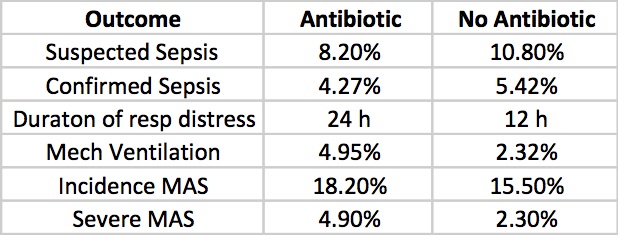

Role of prophylactic antibiotics in neonates born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid (MSAF)—a randomized controlled trial by Goel A et al. This study was done prospectively by randomizing newborns born through meconium stained amniotic fluid to either antibiotics (N=121) for three days or no antibiotics (N=129) after diagnosis. In each case blood and CRP were drawn and if the infant was symptomatic (presence of respiratory distress, lethargy, abdominal distension, temperature or hemodynamic instability, hypoglycemia, apnea, or any other systemic abnormalities) a lumbar puncture and chest x-ray were added. The primary outcome variable was defined as ” the incidence of early (within first 72 h of birth) or late onset (after 72 h of birth) suspect sepsis (clinical symptoms or positive sepsis screen defined as ≥2 positive parameters) and confirmed sepsis (positive blood culture).”

Results

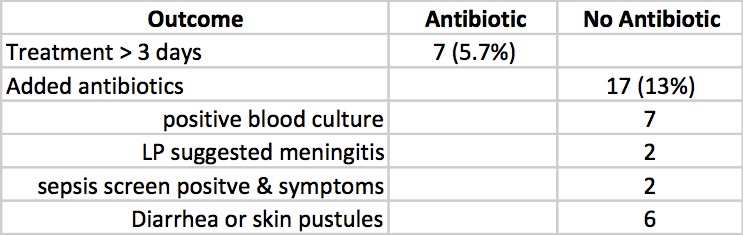

Clinicians in the study were allowed to continue antibiotics past the 72 hours or start antibiotics in the no antibiotic group if they considered an infant to have suspected sepsis or in fact were found to be proven. The outcomes for those possibilities are shown below.

Taking it all together whether you started antibiotics or not the primary outcomes were no different. Furthermore there is no apparent harm based on outcomes that matter including the most important; death (3 in each group) that it does give one reason to pause when considering whether to treat prophylactically with antibiotics for babies born through meconium stained fluid.

What About The Sickest of The Sick

When attempting to answer this question the authors noted the following.

“On doing a subgroup analysis on incidence of sepsis in symptomatic babies (presenting with respiratory distress), both groups were found to have comparable incidence of suspect sepsis (p=0.084). The incidence of confirmed sepsis was more in symptomatic babies, although the total numbers was very few (p=0.01)”

Herein lies the challenge in declaring once and for all that we don’t need antibiotics at all in MAS. While the study was powered to adequately answer the primary outcome, the subgroups are so small that declaring with any confidence that one can stand by and watch infants with severe MAS without starting antibiotics is a tough conclusion to come to. The child though who is born through MSAF and has mild tachypnea as the only symptom I suspect is another story. I might even argue that the baby who is in need of CPAP could be watched and if they deteriorate have antibiotics started. As much as I would love to say none of these babies need antibiotics I would have to admit that I would cave once the baby was ventilated. It is better to provide a couple of days of antibiotics while awaiting blood cultures than to have a patient with sepsis left untreated or at least that is my opinion.

The question is what would you do?

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 9, 2016 | Neonatal, Neonatology, outcome, steroids, Uncategorized

It seems like a sensational title I know but it may not be as far fetched as you may think. The pendulum certainly has swung from the days of liberal post natal dexamethasone use in the 1990s to the near banishment of them from the clinical armamentarium after Keith Barrington published an article entitled The adverse neuro-developmental effects of postnatal steroids in the preterm infant: a systematic review of RCTs in BMC Pediatrics in 2011. This article heralded in the steroid free epoch of the first decade of the new millennium, as anyone caring for preterm infants became fearful of causing lifelong harm from steroid exposure.  Like any scare though, with time fear subsides and people begin asking questions such as; was it the type of steroid, the dose, the duration or the type of patient that put the child at risk of adverse development? Moreover, when death from respiratory failure is the competing outcome it became difficult to look a parent in the eye when their child was dying and say “no there is nothing more we can do” when steroids were still out there.

Like any scare though, with time fear subsides and people begin asking questions such as; was it the type of steroid, the dose, the duration or the type of patient that put the child at risk of adverse development? Moreover, when death from respiratory failure is the competing outcome it became difficult to look a parent in the eye when their child was dying and say “no there is nothing more we can do” when steroids were still out there.

Over the last decade or so, these questions in part have been studied in at least two important ways. The first was to ask whether we use a lower dose of dexamethasone for a shorter period to improve pulmonary outcomes without adverse neurodevelopment? The target population here were babies on their way to developing chronic lung disease as they were ventilated at a week of age. The main study to answer this question was the DART study. This study used a very low total dose of 8.9 mg/kg of dexamethasone given over ten days. While the study was stopped due to poor recruitment (it was surely difficult to recruit after the 2001 moratorium on steroids) they did show a benefit towards early extubation. This was followed up at 2 years with no difference in neurodevelopmental outcomes. Having said that the study was underpowered to detect any difference so while reassuring it did not prove lack of harm. Given the lack of evidence showing absolute safety practitioners have continued to use post natal steroids judiciously.

The second strategy was to determine whether one could take a prophylactic approach by providing hydrocortisone to preterm infants starting within the first 24 hours to prevent the development of CLD. The best study to examine this was by Kristi Watterberg in 2004 Prophylaxis of early adrenal insufficiency to prevent bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a multicenter trial. Strangely enough the same issue of early stoppage affected this study as an increased rate of spontaneous gastrointestinal perforation was noted leading to early closure. The most likely explanation is thought to be the combination of hydrocortisone and indomethacin prophylaxis which some centres were using at the same time. An interesting finding though was that in a subgroup analysis, infants with chorioamnionitis who received hydrocortisone had less incidence of chronic lung disease. (more on this later) Although this of course is subject to the possible bias of digging too deep with secondary analyses there is biologic plausibility here as hydrocortisone could indeed reduce the inflammatory cascade that would no doubt be present with such infants exposed to chorioamnionitis in utero.

Has the answer finally come?

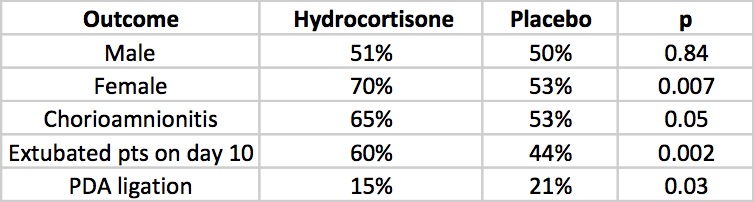

The DART study at 360 patients was the largest study to date to look at prophylaxis as a strategy. That is until this past week. The results of the PREMILOC study have been published which is the long awaited trial examining a total dose of 8.5 mg/kg of hydrocortisone over 10 days. We can finally see the results of a trial without the complicating prophylactic indomethacin trials interfering with results. Surprisingly this study was also stopped early (a curse of such trials?!) due to financial reasons this time. Prior to stoppage though they managed to recruit 255 to hydrocortisone and 266 to control groups. All infants in this study were started on hydrocortisone within 24 hours of age and the primary outcome in this case was survival without BPD at 36 weeks of age.

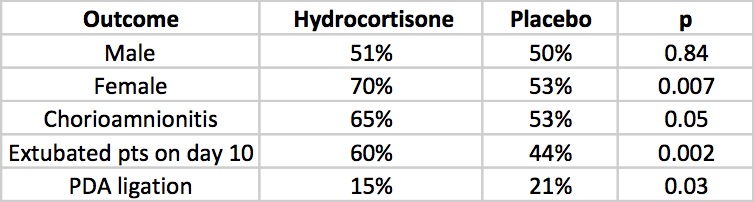

All infants were less than 28 weeks at birth and therefore had a high risk of the combined outcome and despite the study being stopped early there was indeed a better outcome rate in the hydrocortisone group (60% vs 51%). Another way of looking at this is that to gain one more patient who survived without BPD you needed to treat 12 which is not bad at all. What is additionally interesting are some of the findings in the secondary analyses.

The lack of a difference in males may well reflect the biologic disadvantage that us males face overcoming any benefit from the hydrocortisone. In fact for the females studied the number needed to treat improves to 6 patients only! Short term outcomes of less ventilation are sure to please everyone especially parents. Lastly, a reduction in PDA ligation is most probably related to an antiprostaglandin effect of steroids and should be cause for joy all around. Lastly, a tip of the hat to Dr. Watterberg is in order as those infants who were exposed to chorioamnionitis once again show that this is where the real benefit may be.

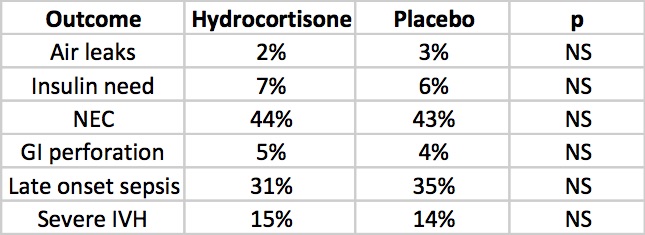

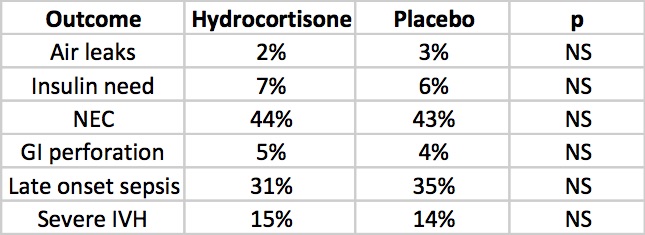

But what about side effects?

The rate of NEC is quite high but is so for both groups but otherwise there is nothing much here to worry the reader. Once and for all we also see that by excluding concurrent treatment with indomethacin or ibuprofen the rate of GI perforation is no different this time around. Reassuring results indeed, but alas the big side effect, the one that would tip the scale towards us using or abandoning treatment has yet to be presented. Steroids no doubt can do great things but given the scare from 2001 we will need to see how this cohort of babies fares in the long run.

The follow-up is planned for these infants and the authors have done an incredible job of recruiting enough patients to make the results likely believable. I for one can’t wait to see what the future holds. If I was a betting man though I would say this ultra low dose of hydrocortisone may be just the thing to bring this therapy finally into the toolbox of neonatal units worldwide. We have been looking for the next big thing to help improve outcomes and good old hydrocortisone may be just what the doctor ordered.

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 5, 2016 | Breastfeeding, Breastmilk, Uncategorized

I woke up this morning and as I do everyday, scanned the media outlets for news that would be of interest to you the reader. One such article today was about how breast milk may give babies a metabolic boost due to micro RNA present in the milk. This got me thinking about how natural a thing this breast milk is and how substances within interact with the baby receiving it. After that point I recalled writing about a challenge to the statement that breast milk is natural and thought you might like to see what I considered to be an outrageous piece of journalism from last year.

The premise of the article is that by reinforcing that breastfeeding is natural we may hamper initiatives to increase vaccination in many parts of the world and in particular North America I would think. The idea here is that if we firmly entrench in women’s heads that natural is better then this will strengthen the conviction that we should not vaccinate with these “man made” unnatural vaccines. I am sorry to be dramatic about this but I think the argument is ridiculous and in fact dangerous.

The Definition of Natural

“existing in nature and not made or caused by people : coming from nature”

From the Mirriam Webster dictionary

Breastfeeding satisfies this definition pure and simple and there is nothing that anyone should say to suggest otherwise no matter what the motive is. The shift from formula to breastfeeding has been predicated on this notion and a plethora of literature on the subject demonstrating reductions in such things as infections of many kinds, diarrhoea, atopic disease in the first year of life as examples. In my world of premature infants additional reductions in NEC, bloody stools, have been seen and more recently in some cases improved neurodevelopmental outcomes.

In this case of irresponsible journalism a better approach if you were wanting to use the natural argument with respect to vaccines is to promote just that.

Vaccines are Natural

Someone will no doubt challenge me on this point as it would be a fair comment to say that there are artificial substances added to vaccines but there is no question the organisms that we vaccinate against are natural.

Think about this for a moment. All of the vaccines out there are meant to protect us against organisms that exists in NATURE. These are all bacteria or viruses that have likely existed on this planet of ours for millions of years. They are found everywhere and in many cases what we are doing when we give such vaccines are providing parts of or weakened versions of these natural organisms in order for us the human to mount a protective response.

This protective response is NATURAL. If we didn’t vaccinate and came across the fully virulent pathogen in NATURE our bodies would do exactly what they do when a vaccine is given to us. Our immune system would mount a response to the organism and start producing protective antibodies. Unfortunately in many cases this will be too little too late as the bacteria or virus will cause it’s damage before we have a chance to rid ourselves of this natural organism.

This is the basis of vaccination. Allow our bodies a chance to have protection against an organism that we haven’t been exposed to yet so that when it comes we have a legion of antibodies just waiting to attach this natural organism.

CNN Didn’t Get It Right

In the article which is based on a paper entitled the Unintended Consequences of Invoking the “Natural” in Breastfeeding Promotion by Jessica Martucci & Anne Barnhill the authors admit that the number of families that this actually would impact is small. the question then is why publish this at all. Steering families away from thinking that breastfeeding is natural is wrong. Plain and simple.

If the goal is to improve vaccination rates, focus on informing the public about how NATURAL vaccinations actually are and don’t drag breastfeeding down in order to achieve such goals. As a someone who writes themselves I am well aware of how personal biases creep into everything we write. I am aware of the irony of that statement since it is clear what side of the argument I sit on. While I peruse CNN myself almost daily I think the editors either missed the larger message in this piece or perhaps felt the same way. A disclosure that “the opinions of the author do not necessarily represent those of the network” does not cut it for what I would consider responsible journalism in this case.

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 3, 2016 | antenatal steroids, Neonatal, Neonatology, Uncategorized

What a hard topic to resist commenting on. This was all over twitter and the general media this week after the New England Journal published the following paper; Antenatal Betamethasone for Women at Risk for Late Preterm Delivery. The fact that it is the NEJM publishing such a paper in and of itself suggests this is a top notch study…or does it?

In case the idea of giving antenatal steroids after 34 weeks sounds familiar it may be so as I wrote about the use of such an approach prior to elective c-section in a previous post; Not just for preemies anymore? Antenatal steroids for elective c-sections at term.

Is there a benefit to giving antenatal steroids from 34 0/7 – 36 5/7 weeks?

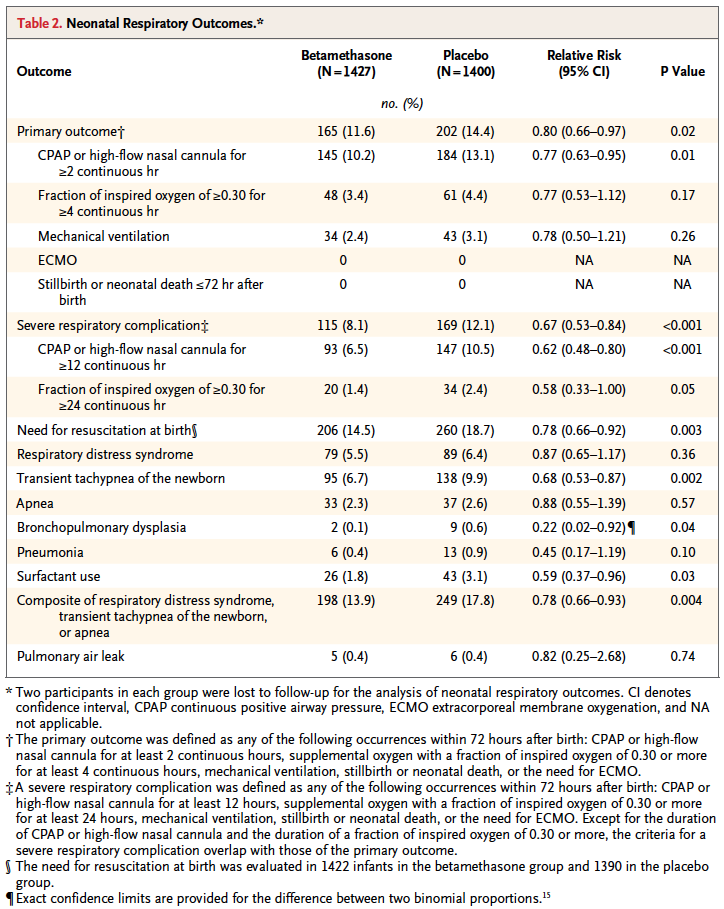

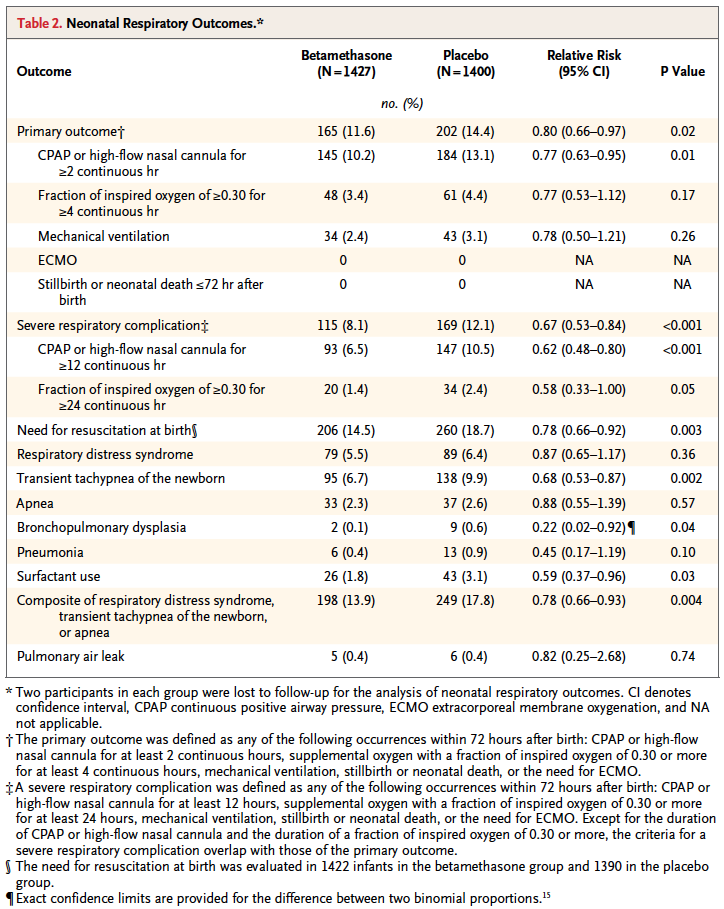

That is the central question the authors here sought to answer. Would women who had a high risk of delivering during this time period have less risk of a composite primary outcome of treatment in the first 72 hours (the use of continuous positive airway pressure or high-flow nasal cannula for at least 2 hours, supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of at least 0.30 for at least 4 hours, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or mechanical ventilation) or stillbirth or neonatal death within 72 hours after delivery.

On the surface this seems like a very worthwhile set of outcomes to look at and the authors found in the end some pretty remarkable findings in a total of 2827 women randomized to placebo or betamethasone.

Looking at the results one sees that the primary outcome showed a significant difference with 2.8% less infants experiencing these conditions. However, when one looks at the details the only contributor to this difference was the need for CPAP or HFNC for >= 2 hours. A need for over 30% FiO2 for > 4 hours was also not different. No differences were noted in mechanical ventilation, ECMO, deaths whether stillbirths or neonatal deaths. Curiously, significant differences for secondary outcomes were seen with incidence of severe respiratory distress, and need for CPAP for over 12 hours.

These results are not truly that surprising at least for the primary outcome as if you asked most people working in the field of Neonatology how likely death, need for ECMO or even mechanical ventilation are from 34 – 36 weeks they would tell you not very likely. The other thing to consider is that the only real significant difference was noted for infants needing CPAP or HFNC for at least 2 hours. While this would interrupt maternal infant bonding, it wouldn’t necessarily mean an admission but rather in some cases observation and then transfer to the mother’s room.

Is it worth it?

To answer this question you need to know the best and worst case scenarios I suppose. Based on the reduction of 2.8%, you would need to treat 35 women with betamethasone to avoid the primary outcome but of course there is a range based on the confidence intervals around this estimate. The true estimate lies somewhere between 18 – 259 to avoid the outcome. Having said that, the estimate to avoid severe distress is 25 patients with a range of 16 – 56 which is pretty good value. In a perfect world I would probably suggest to women that there seems to be a benefit especially if one notes that in this study only 60% of the women received 2 dose of betamethasone so if rates of administration were higher one might expect and even better outcome. Ah but the world is not perfect….

There is only so much betamethasone to go around.

I find it ironic but the same day that this article came across my newsfeed so did a warning that we were about to run out of betamethasone vials in a certain concentration and would need to resort to another manufacturer but that supply may also run out soon as well. The instructions were to conserve this supply in the hospital for pregnant women.

In Canada as reported by the Canadian Neonatal Network in 2010, 38.1% of babies admitted to NICUs were below 34 weeks. Given that all babies would be admitted to NICUs at this gestational age and below that likely represents the percentage of births in those ages. An additional 31.8% or almost an equal number of babies will be born between 34 0/7 to 37 0/7 weeks meaning that if we were to start treating women who were deemed to be at risk of preterm delivery in that age range we would have a lot of potential women to choose from as these are the exact women in this strata who actually delivered early in Canada.

If I am forced to choose whether to give betamethasone to the mothers under 34 weeks or above when the resource we need is in scarce supply I don’t think there is much choice at all. Yes, this article comes from a reputable journal and yes there are some differences some of which are highly significant to consider but at least at this time my suggestion is to save the supply we have the babies who will benefit the most.

The 3 dose schedule was used for those infants born between 29 0/7 and 35 weeks gestational age who had a risk factor score of 42 or more. Interestingly at the end of the RSV season, depriving such infants of 1 or 2 doses did not appear to impair the ability of the infant to maintain protective levels.

The 3 dose schedule was used for those infants born between 29 0/7 and 35 weeks gestational age who had a risk factor score of 42 or more. Interestingly at the end of the RSV season, depriving such infants of 1 or 2 doses did not appear to impair the ability of the infant to maintain protective levels.

Like any scare though, with time fear subsides and people begin asking questions such as; was it the type of steroid, the dose, the duration or the type of patient that put the child at risk of adverse development? Moreover, when death from respiratory failure is the competing outcome it became difficult to look a parent in the eye when their child was dying and say “no there is nothing more we can do” when steroids were still out there.

Like any scare though, with time fear subsides and people begin asking questions such as; was it the type of steroid, the dose, the duration or the type of patient that put the child at risk of adverse development? Moreover, when death from respiratory failure is the competing outcome it became difficult to look a parent in the eye when their child was dying and say “no there is nothing more we can do” when steroids were still out there.