by All Things Neonatal | Jul 12, 2015 | General Comments, health care, Neonatal, Neonatology, preemie, Prematurity

Living in Canada we are privileged to have a universal health care system. Privileged in the sense that all citizens are entitled to the same level of care regardless of economic circumstance although the monetary costs to the tax payer is another story and forms the basis of most arguments in the US against adopting such a system down south. My goal of this post though is not to enter into a debate about which system is superior but rather speak of the dollars and cents attributable to being born too early or too small.

In the US such measurements are simpler as costs are more easily measured in a private health care system but each health care region in Canada can measure to a certain degree the costs associated with a hospital stay. Certainly the story of Raquena Thomas made this clear to me. In 2007 she was born in Edmonton after her mother left Jamaica for a visit with family in Edmonton. After delivering she was found to have hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) and went on to have the first stage of the Norwood procedure. What followed was a bill to the mother for $162576 and for commentary on the discussion that ensued about who should pay the bill see the article here. As I was working at the Stollery Children’s Hospital at the time and cared for this infant it was clear to me after this experience that the hospital indeed has a clear method to calculate costs even if we the taxpayer are blind to such calculations.

Now HLHS is a condition that affects very few infants a year in any given province but what about low birth weight and preterm birth? This as we say in Neonatology is our bread and butter. In 2009 Lim et al published data on the Canadian population in attempt to ascertain the health care costs for these groups of patients (CIHI survey: Hospital costs for preterm and small-for-gestational age babies in Canada)

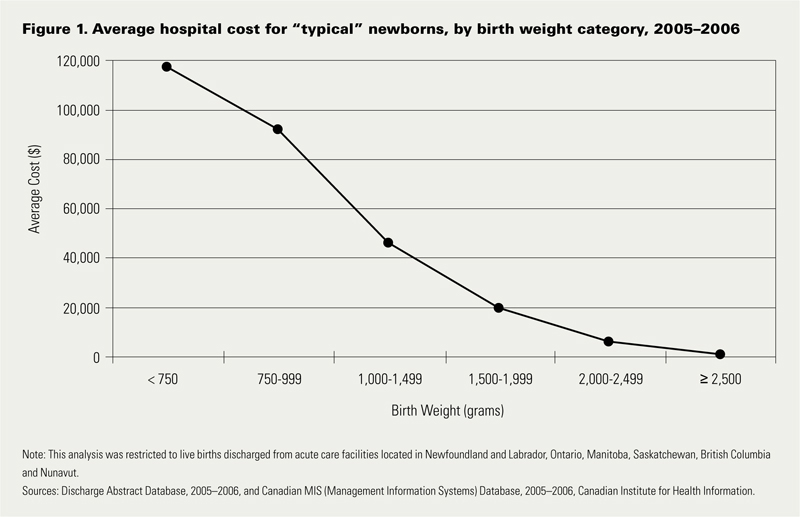

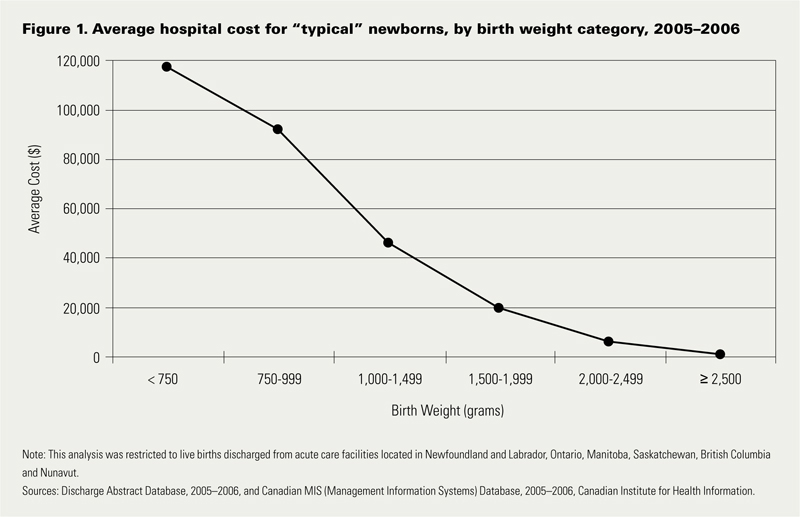

In this period 1 in 7 babies was born either preterm or small for gestational age. If specifically looking at infants < 2500g defined as low birth weight this represented 6% of all babies born. When you factor in that there were 350000 babies born in that year in Canada we are looking at about 21000 babies nationally.  Looking at the costs for these infants one sees a direct relationship between decreasing birth weight and increasing costs in the hospital. This should not be surprising to anyone. It should be noted though that the paper provides average costs only without standard deviation or ranges. As you would expect, the costs for a patient with severe HIE or NEC would be higher than the 26 week infant who has a very smooth course and does not have a symptomatic PDA, severe IVH or any other significant disability during their course.

Looking at the costs for these infants one sees a direct relationship between decreasing birth weight and increasing costs in the hospital. This should not be surprising to anyone. It should be noted though that the paper provides average costs only without standard deviation or ranges. As you would expect, the costs for a patient with severe HIE or NEC would be higher than the 26 week infant who has a very smooth course and does not have a symptomatic PDA, severe IVH or any other significant disability during their course.

The data looking at such costs is scare with respect to the Canadian landscape and even more difficult to determine has been lifetime costs or at least incremental costs after leaving the hospital environment. I was delighted to see that former colleagues of mine in Edmonton have published a new paper examining both the extent of health service utilization (HSU) attributable costs in the year following discharge of both LBW and normal birth weight peers in Alberta (abstract here). Not surprisingly, smaller babies have more medical needs. In this study LBW patients had an average of 5.9 outpatient services and 1.1 visits to the ER in the first year of life compared to 2 and 0.9 in the normal birth weight peers. Physician services were double with 22.7 office visits compared to 11.9 in the NBW group. The costs to the Health Care system overall are represented in the table below which demonstrates that the LBW infants make up 37% of the total health care costs of newborns yet represent only 6% of the population. In terms of risk factors for LBW they were high prepregnancy weight, aboriginal women and low socioeconomic status. Efforts to lessen the incidence of the first and third factor in our pregnant population would be a good target for public health efforts. Bear in mind that the costs outlined below are in addition to the costs in the hospital.

| BW Category |

Cost per patient |

Patients |

Cost to System (millions) |

| NBW |

$3,942 |

43207 |

182 |

| LBW <2500 |

$33,096 |

3123 |

108 |

| 1500 – 2499g (MLBW) |

$20,467 |

2571 |

53 |

| 1000 – 1499g (VLBW) |

$83,895 |

278 |

23 |

| < 1000g (ELBW) |

$117,546 |

274 |

32 |

The analysis provided in this paper does not specify out the costs by certain conditions such as NEC or BPD so all we have to go on are averages for HSU and cost. It does however raise a point which I believe is crucial to any discussions with respect to expanding programs within the hospital. We need to refocus administration at both the hospital level and at the funding source (our provincial governments) as to the true costs of the conditions that we are trying to prevent. It is only through looking at the costs of both the hospitalization and after discharge that we can truly come to understand the cost effectiveness of expanded programs or new treatment modalities.

Donor breast milk is one that I believe serves as a good example of a program that is in need of expansion in many places in the country but is hampered by the perception of high up front costs. The average cost of this milk is about $4 per ounce. I will simplify the math a little as there would be a phase of escalating the volume per day and a wean at the end but let’s say we have a 1.5 kg infant that we want to treat with DBM for a period of 4 weeks. The cost to do this assuming a TFI of 150 mL/kg/d would be a little over $800 per patient so with the increasing phase, wean and adjusting for some weight gain let’s say $1000 per patient. If there were 200 such patients in your hospital each year the annual cost would be $200000 which on the surface seems like a lot of money. From the most recent cochrane review though comparing formula to donor milk the risk ratio to develop NEC is 2.77 meaning that a preterm baby who receives formula is nearly three times as likely to develop NEC. Ignoring differing rates of NEC by hospital let’s just use the concept that we could prevent one case of NEC a year with such a strategy. The cost of medical NEC is somewhere between 100-140K while surgical is 200 – 240K. The in-hospital costs of preventing just one case nearly pay for or exceed the cost of the entire years supply of DBM. If you add to this the cost of the following years of physician visits, consultants, testing, special diets and investigations and procedures these patients receive the costs are more than covered from just one patient.

Health care budgets are no doubt a difficult thing to balance but the point of all of this is that when determining whether to spend our precious health care dollars we must look at not only the impact during the hospitalization but for years after if we truly modify future risks as well.

by All Things Neonatal | Jun 11, 2015 | bioethics, Prematurity

A judge has granted a man the right to a physician assisted death in Manitoba as reported by the CBC yesterday. Given this landmark ruling based on a change in the Canadian stance allowing such decisions the question turns to children and then neonates. At the present time this stance does not apply to these populations but it is fair to ask the question… what if it did?

The Groningen Experience

As the saying goes “the more things change the more they stay the same”. In 2005 I was but a year into my career as a staff Neonatologist and we were discussing whether we should resuscitate 22 and 23 week infants. Sound familiar? In the back and forth discussion, one of the things that came up from time to time was that the Dutch at least had the option of euthanasia to fall back on if they decided to resuscitate an infant and then the family or care providers changed their minds. It was not necessary to prolong the suffering of the family and patient in the face of futility. I remember being shocked by such a ruling in Holland’s legal system, as euthanizing a newborn in North America was and still is today something that most could not come to grips with. Nonetheless the Groningen protocol as it became known, was introduced in 2004 by Eduard Verhagen the medical director of the department of Pediatrics at the University Medical Center Groningen and became endorsed almost 10 years ago to the day by the Dutch Society of pediatrics.

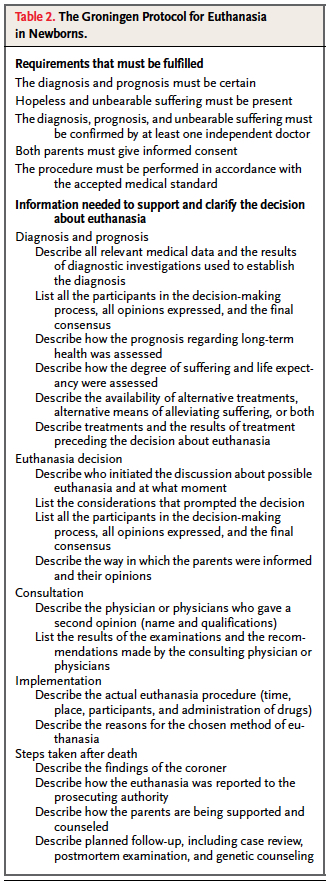

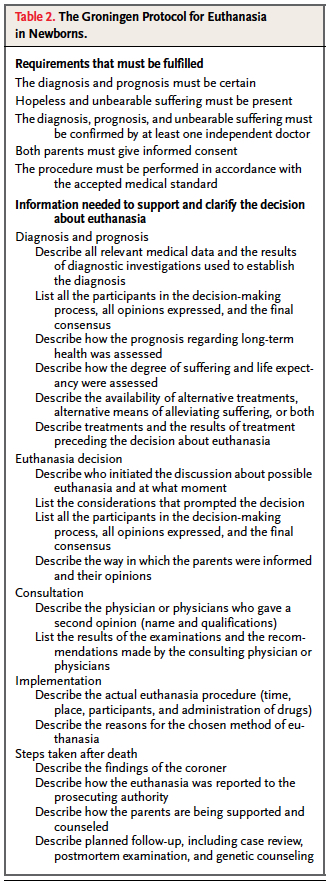

Although many of you may be caught off guard as you read this, it really did generate a fair bit of attention here in North America and has been the subject of many articles and news reports over the years. The Groningen protocol is quite extensive as shown in the table.

The key elements to the protocol are:

(1) diagnosis and prognosis must be certain

(2) hopeless andunbearable suffering must be present

(3) a confirming second opinion by an independent doctor

(4) both parents give informed consent

(5) the procedure must be performed carefully, in accordance with medical standards.

There were some that worried birth at 22 weeks would meet this criteria and lead to ELBW infants being euthanized after a few hours of life rather than using the method of comfort care that we are accustomed to in North America if carrying on seemed futile. Although the outcome is the same, the route to get there is clearly different.

So the question then is what has happened in Holland since this practice was made permissible by the courts? In 2005 shortly after the protocol was introduced, Verhagen published a piece in the NEJM reviewing all the cases of newborn euthanasia from 1997 – 2004. In all there were 22 cases each of which involved a case of spina bifida and in most quite severe. Interestingly there were no cases of premature infants.

What Happened in Holland Over Time

In 2013 he published a a second article in which he acknowledged that worldwide people were concerned that a slippery slope would occur in Holland. As such, he examined all neonatal deaths in NICU from 2005 – 2010. Withholding or withdrawing treatment was the reason for death in 95% of cases. During that period only 1 patient with Osteogenesis Imperfecta type II was classified as euthanasia. This dramatic decline from the pre 2005 state may seem surprising but it is offset by an increase in second trimester terminations after ultrasound at 20 weeks became standard practice in Holland. Previously it was only offered to those over 35 years of age. In fairness, he does acknowledge that there could be underreporting occurring but as he points out, given the lack of consequence in the legal system provided that the protocol is followed there would be little reason to not report as such. There are some cases of paralytic use described in what was classified as withdrawal of support in which the medication was used to treat the gasping efforts of the infant in the last moments of life. While these cases are technically euthanasia, in that the end of life is no doubt hastened, at that point it could be measured in minutes. Is that so wrong if the team views this as distressing to the patient and family. Perhaps yes in some eyes but ask yourself if it is that different from knowingly pushing doses of narcotics higher in the same circumstance which achieves the same end point at times.

So it would seem that the rate did not increase and in fact a marked decrease actually occurred. Curiously a second study has been just released Dutch neonatologists have adopted a more interventionist approach to neonatal care. The study is a joint effort by the Dutch including Verhagen and Dr. Janvier of St. Justine in Montreal who we were fortunate to hear speak recently in Winnipeg. The paper describes a very interesting phenomenon. The authors compared all infants born at > 22 weeks who either died in the delivery room or in the NICU in two epochs; 2001 – 2003 and 2008 – 2010 specifically looking at measures of intervention in the two periods. Would more legal clarity making it permissible to end a life lead to higher mortality in the second period, as a marker of less invasiveness? In both periods there was only one patient that received comfort medication in the delivery room. Furthermore, there were no differences in the number of patients dying in either site. As described in the 2013 paper there were increases in the rate of termination of pregnancy in the second period but there is no support for the argument that the Dutch became less interventionist after the relaxing of laws on euthanasia. Lastly as further evidence that they went the other way, length of stay increased significantly in the NICU from 11.5 to 18.4 days in the second period reflecting less withdrawal in part.

What Conclusions Can We Draw About Our Own Populations?

As the title of this post suggests, it would appear that much of the worry in 2005 has simply not come to pass. Yes there has been a shift to termination for congenital anomalies in the second trimester but that would be no different from our practice in North America. I can’t help but draw parallels between the arguments for the legalization of some drugs such as marijuana and euthanasia. The decriminalization of the former is expected to have the benefit of reducing crime and perhaps even abuse of the drug as it no longer becomes as attractive once it is no longer “sinful”. Has a similar effect happened in Holland perhaps by bringing the discussion to the world stage? It may well be that the change in law in Holland created the opposite effect whereby the Dutch painfully aware that they were being “watched” became even more reluctant to hasten the time of death in these situations. There is no doubt that something changed after 2005 as they became more interventionist and not less.

A final thought has to do with a thought that Dr. Verhagen raises in the 2013 piece. Has the transition to a model of terminating pregnancies in the second trimester been a good or bad thing. He argues that ultrasound is not as predictive in terms of diagnosis as examining a patient after birth. When an infant is in front of your eyes, facial features combined with enhanced imaging may reveal a change in diagnosis compared to what is determined antenatally. Similarly, a patient with a seemingly inoperable heart defect may have a slightly different scan after delivery which provides some options for the family. If examination after birth is superior to antenatal diagnosis in terms of accuracy, are we doing the right thing by forcing families to decide on termination prior to delivery? In Holland the option exists although clearly not being taken to assess a patient after birth and then if the diagnosis meets the Groningen protocol a life can be ended early. It can be argued of course that euthanasia is not the only option and that one can choose not to feed and withdraw life-sustaining treatment.

The question that I will leave you with though is as a parent would you want to watch your infant die after 5-7 days dehydration or end their life given the outcome is the same on the same day you choose “compassionate care”? Which is the more humane decision when the outcome is the same?

by All Things Neonatal | Jun 4, 2015 | Neonatology, Prematurity, Vaccination

Ask any health care professional how our tinyest babies fare after an immunization and they will tell you “not well”. In fact the belief is so pervasive that we go out of our way to find excuses to delay immunizations. I have heard myself uttering such comments as “today is not a good day” or “let’s wait until there is greater respiratory stability” or simply “they are too sick”. Perhaps this tendency develops because we are shaped by our past experiences and if we have had a baby get intubated who was on CPAP after an immunization, we subconsciously say to ourselves “that won’t happen again”.

By no means am I writing an anti-vaccination piece but rather exploring our behaviours and trying to come up with a means of changing them. Adverse Events After Routine Immunization of ELBW Infants was published on this very topic this week and with nearly 14000 infants from 23 – 28 weeks included who received their first 2 month immunization, it certainly caught my attention!

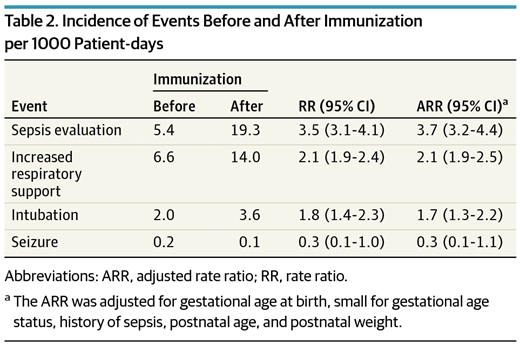

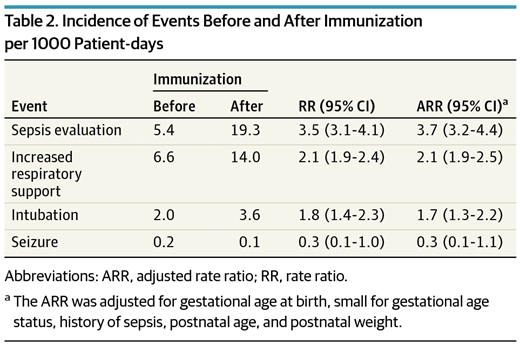

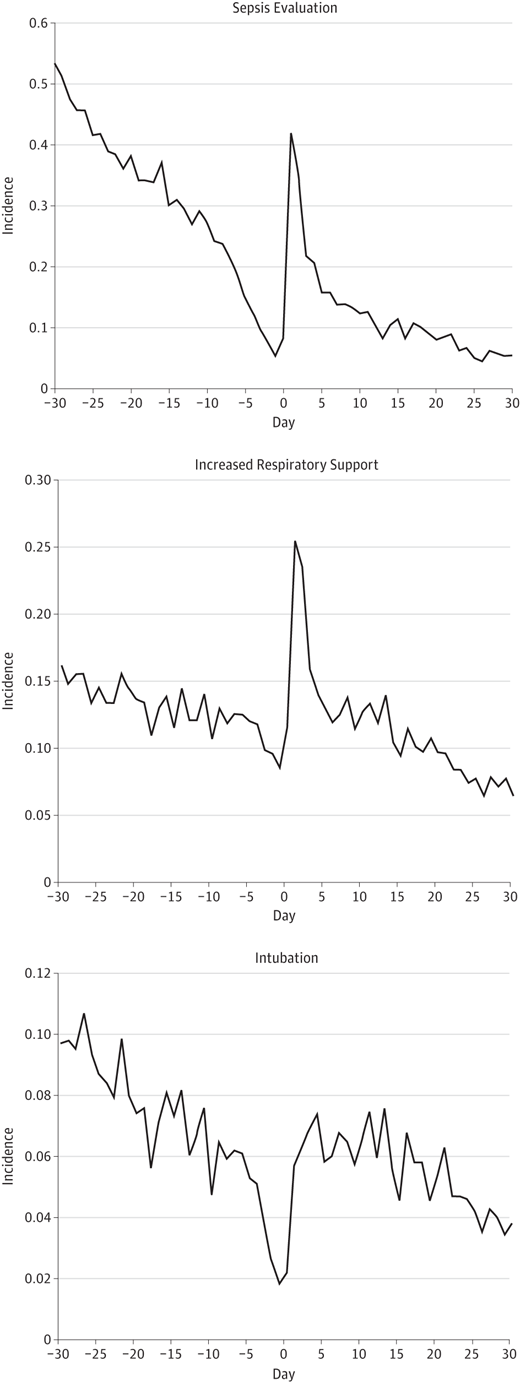

The table indicates the risks of certain adverse events in the 3 days preceding the immunization to the 3 days afterwards.  What you will note is that the evaluations for sepsis increased 4X, Respiratory support and intubation almost 2X, with no difference in seizures. It is important to note that the definitions for sepsis were based on two blood cultures being drawn rather than fever alone. Curiously with respect to sepsis there was an increase in the number of positive cultures as well from 2.1 to 3.8% in the evaluations that were done before and after. It is worth pointing out though that I can find no analysis of those results to determine if they were statistically different so at most it is an “interesting” finding.

What you will note is that the evaluations for sepsis increased 4X, Respiratory support and intubation almost 2X, with no difference in seizures. It is important to note that the definitions for sepsis were based on two blood cultures being drawn rather than fever alone. Curiously with respect to sepsis there was an increase in the number of positive cultures as well from 2.1 to 3.8% in the evaluations that were done before and after. It is worth pointing out though that I can find no analysis of those results to determine if they were statistically different so at most it is an “interesting” finding.

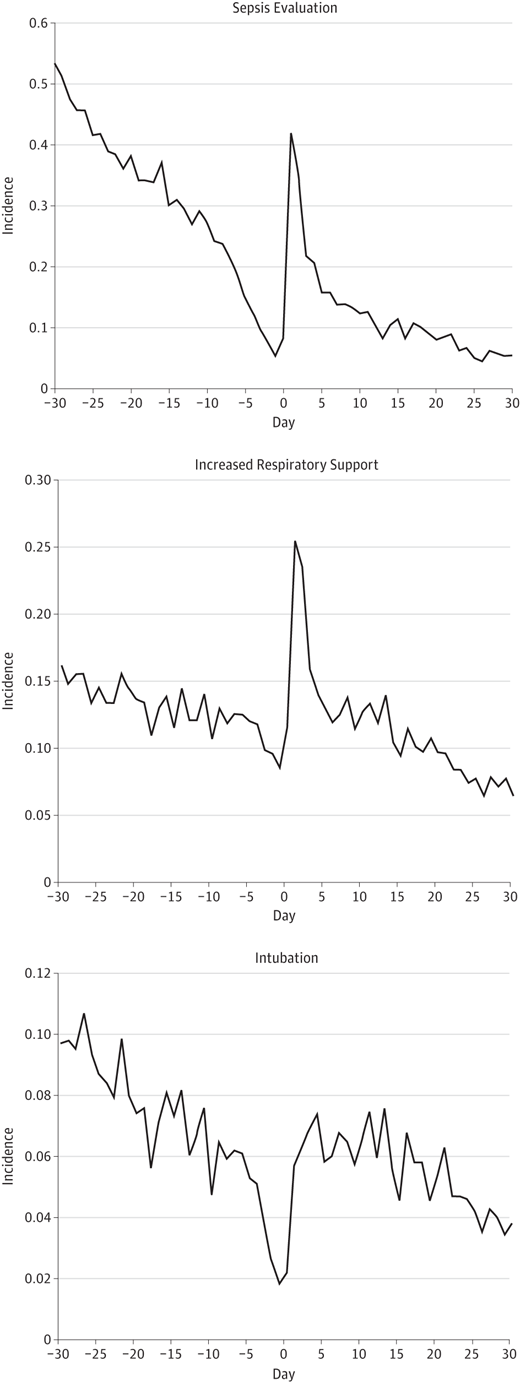

The figures below demonstrate the rate of the same adverse events before time zero and then afterwards for the same duration as in the table.

What you notice aside from the rise in adverse events is a sharp decline in the rate of adverse events just prior to the immunization and then a sharp rise after it is given.  The steep decline just prior to immunization is known as the Healthy Vaccinee Effect. That is to say that we may see a higher rate of complications simply due to the fact that we wait for kids to be at their healthiest and when they have only had one or two days without apnea or are off their antibiotics that is when we choose to give the vaccine as we believe they can now “handle it”. What we have created is a special sample of patients that actually does not reflect the whole population. What I mean by this is that the response of all patients to their vaccines in this age group might be quite different with no increases in any adverse events if we paid no attention to our preconceived notions that the infant in our care is “too sick” to get their immunization. When we only immunize those kids that are at their best, the likelihood of them deteriorating is higher than when they were “worse”.

The steep decline just prior to immunization is known as the Healthy Vaccinee Effect. That is to say that we may see a higher rate of complications simply due to the fact that we wait for kids to be at their healthiest and when they have only had one or two days without apnea or are off their antibiotics that is when we choose to give the vaccine as we believe they can now “handle it”. What we have created is a special sample of patients that actually does not reflect the whole population. What I mean by this is that the response of all patients to their vaccines in this age group might be quite different with no increases in any adverse events if we paid no attention to our preconceived notions that the infant in our care is “too sick” to get their immunization. When we only immunize those kids that are at their best, the likelihood of them deteriorating is higher than when they were “worse”.

We know from previous literature that ELBW infants have higher rates of apnea and need for respiratory support after their vaccines. If we gave them an immunization when they were on CPAP or a higher dose of caffeine would we notice the impact as much? By waiting till they have weaned off CPAP or outgrown their dose of caffeine we are setting ourselves up for a setback.

Similarly perhaps the optimal time to give the vaccine is when they are actually on an antibiotic for a sepsis evaluation or have had a CRP for one reason or another in the preceding 24 hours. Would a mild fever after the vaccine trigger the same response to do a septic workup or would you take comfort in knowing your patient was already on antibiotics or had no signs of inflammation prior to the vaccine?

In summary I question if I have had it all wrong. I am not saying to give a vaccine to a patient who is on high frequency ventilation and inotropes due to septic shock but rather when they are recovering and off the inotropes but still ventilated what is the harm? They are already intubated, and covered with antibiotics. Seems to me to be the perfect conditions to prevent me from either escalating their respiratory support or doing a septic workup. They are already covered!

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 30, 2015 | Prematurity

August 4th, 2020 – Since this post was originally published I have published in this area with one of our former trainees and current fellow in Toronto M. Durst. Her paper Atypical case of preterm ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is available through the link in full text via open access!

Thus far in my career, I have been called to the bedside to look at a female ex-preterm infant several times due to the complaint of swelling that usually extends from the lower abdomen to the upper thighs. Usually the clitoris and hood are swollen as well and at times raises the suspicion of cliteromegaly. The enlarged clitoris then prompts the question of whether the patient could be virilized from Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia or perhaps even be male in extreme cases. As I think back on some of these babies, nursing often has expressed concerns that the infants are uncomfortable and have either been treated with furosemide (unsuccessfully) or pain medication for the perceived discomfort.

As you might expect from the first paragraph I believe I have found the answer which came to me through a circuitous route. We had a patient in the hospital recently whose phallus was small for his gestational age. After consulting the Pediatric Endocrinologist on service we performed a hormonal workup which excluded hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (small phallus due to a lack of male hormones) and insensitivity to testosterone. Our Neonatal service was advised that this child would likely experience penile growth during “Mini Puberty” I don’t know about you but I had never heard of the term so I began a search that culminated in me writing this post to hopefully bring others up to speed.

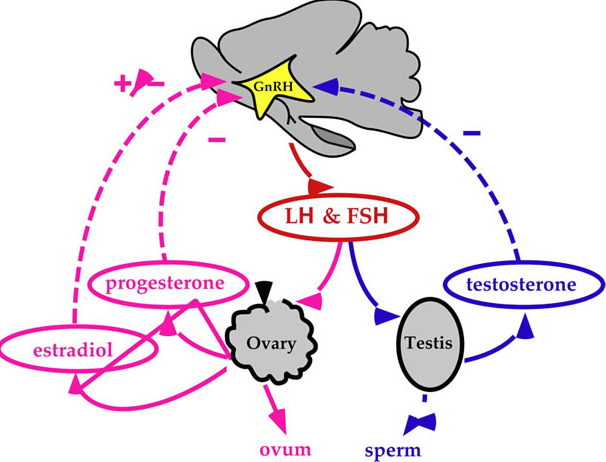

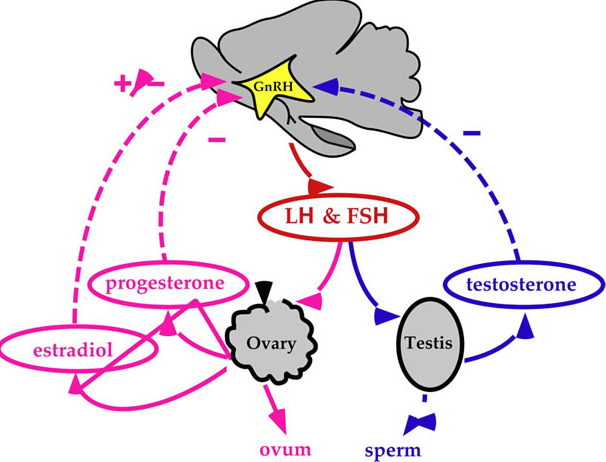

Mini puberty is secondary to the normal rise in testosterone that occurs after delivery. In utero both estrogen and testosterone inhibit GNRH with estrogen from the placenta being the most potent inhibitor. Once the placenta is removed this inhibition is lost leading to LH and FSH levels rising which peak between the 4th to 10th week that finally begin to decline after 7 months of age. The level of testosterone similarly peaks by 3 months and reaches pre-pubertal levels by 6-9 months. During this time there is an increase in testicular volume and less so penile length but a patient such as ours might reach a normal length with such stimulation if the length was not extremely short before “Mini Puberty”.

In female infants it is somewhat different in that pre-pubertal levels of estradiol are reached by two months of age. Given the lack of stimulation from excessive levels of estradiol how can we tie this back to the question of genital swelling?

In 1985 Sedin G et al published a case series of 4 premature infants who demonstrated swelling of the lower abdomen, labia and upper thighs.  In each case the etiology was found to be the same; estradiol producing ovarian cysts. In one case the cyst was removed and with it the edema resolved and in the other cases progesterone was utilized to suppress production of Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GNRH) and with it production of FSH and LH, thereby reducing the estradiol levels. Ultrasound in each case also revealed uterine enlargement consistent with over stimulation. What is it that causes this phenomenon is unknown for sure but it is certainly curious that the condition only seems to affect preterm infants born at < 29 weeks. Furthermore the timing of the edema is consistently at 36 – 39 weeks CGA. Sedin postulates that the reason for this is that the hypothalamic pituitary axis is immature in these preterm infants and does not provide the negative feedback to reduce LH and FSH compared to the term infant in which such sensitivity is present.

In each case the etiology was found to be the same; estradiol producing ovarian cysts. In one case the cyst was removed and with it the edema resolved and in the other cases progesterone was utilized to suppress production of Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GNRH) and with it production of FSH and LH, thereby reducing the estradiol levels. Ultrasound in each case also revealed uterine enlargement consistent with over stimulation. What is it that causes this phenomenon is unknown for sure but it is certainly curious that the condition only seems to affect preterm infants born at < 29 weeks. Furthermore the timing of the edema is consistently at 36 – 39 weeks CGA. Sedin postulates that the reason for this is that the hypothalamic pituitary axis is immature in these preterm infants and does not provide the negative feedback to reduce LH and FSH compared to the term infant in which such sensitivity is present.

Additionally another theory is that vascular endothelial growth factor released from ovarian granulosa and thecal cells may be involved. Since the report by Sedin, Starzyk et al have reported an additional 9 patients with such edema and ovarian cysts http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19039238

I suspect that many Neonatal units across the World have encountered such patients and tried a collection of treatments including furosemide or other diuretics along with fluid restriction. Unfortunately there has not been widespread description of such patients and it is my hope that with this post, awareness will increase of both “Mini Puberty” and “Genital Edema in females”. What is really needed in the latter is consultation with Endocrinology to perform provocative Hypothalamic Pituitary Axis testing and an ultrasound to confirm the presence of uterine hypertrophy and cysts. Treatment with progesterone or some other inhibitor of the GNRH will likely bring about resolution in a timely fashion without exposing the infant to a multitude of testing. Lastly such infants are often described as appearing uncomfortable which may be related to the ovarian cysts or the swelling but in either case adequate analgesia should be provided.

This truly is a post that I hope is shared with others so that we can increase awareness as there are certain to be cases in units right now that might do well to understand this condition.

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 27, 2015 | Neonatal, Prematurity, Transport

In the modern day NICU thermoregulation is something that we are concerned with but due to the availability of servo controlled warmers in delivery suites hypothermia is becoming a rarer event. Add to that we have access to polyurethane plastic wraps for our smallest infants and admission into servo controlled environments with additional humidity control and we have all the tools available to prevent hypothermia and it’s consequences. Such adverse effects include hypoglycemia and lethargy the latter being a common cause of septic work-ups leading to increased antibiotic usage. Such interventions are both painful and put the infant at risk of complications related to antibiotic use such as increased resistance, or altered microbiome with puts them at an increased risk of NEC. Just published online today in fact, researchers from the Canadian Neonatal Network have shown a U shaped relationship between admission temperature and outcome (morbidity and mortality including ROP, BPD and NEC etc) from being hypo or hyperthermic on admission. http://bit.ly/1H2384x. Clearly there is harm from being hypothermic so maintaining normothermia must be of prime importance in the care of our patients.

Sadly such technology does not exist everywhere and in developing nations the common alternatives may be non-servo controlled warmers, warmed blankets, cribs or Kangaroo Care (Skin to Skin). There is no question that Skin to Skin (STS) care provides excellent thermoregulation and bonding for the parent and child but what do you do when the mother or father is unavailable (ill after delivery) or unwilling? The benefits of STS to prevent hypothermia and infant mortality are striking and were first described in 1978 by Drs Rey and Martinez. A brief history of the practice following their description can be found here http://bit.ly/1CgDm9t.

This month Bhat SR et al published the following article (http://1.usa.gov/1HRRZoo) Keeping babies warm: a non-inferiority trial of a conductive thermal mattress. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015 Mar 19

This study compared the above mentioned modes of warming infants with a warming mattress over a four hour period in a non-inferiority trial of temperature regulation. The concept here is that the authors were simply trying to show that the use of the mattress as a thermoregulation device was just as good as the other means of controlling temperature. For a video demonstrating this technology please look at http://embraceglobal.org/. Briefly the system involved a containment device that has a paraffin based material that when preheated with an inexpensive electric heater absorbs the heat and then when placed in a pouch provides constant temperature regulation for a 4-6 hour period. The pouch was subsequently placed in a mattress with wrap as shown in the video to yield the desired temperature regulation. The authors of this study looked at a total of 160 infants with a birthweight between 1500 – 2499g in four centres located in India and observed infant temperatures hourly over a four hour period. Temperatures were compared in each case between those randomized to the standard temperature regulation strategies in each centre versus the warming mattress. The findings were in agreement with the hypothesis of the study in that the mattress was equivalent to the other methods of regulating temperature.

Specifically the temperature of the infants during the 4 hour trial period was 0.11 +/1 0.03 degrees higher than the other methods. None of the infants developed hypothermia during the trial and while 5 of the infants randomized to the mattress were withdrawn from the study it was due to the temperature of the infants being in the upper range of an acceptable level between 37.5 – 37.9 degrees.

My first reaction when I read this paper was that it was interesting but did it really apply to our population? As the authors suggest it was not a blinded intervention and over time, temperature regulation improved so could the Hawthorne effect be at play? The infants in this study were larger (1500 – 2499g) than the infants that we would typically put at highest risk. Also how useful is an intervention that only lasts 4-6 hours when we need to care for these kids for weeks? Lastly, I live in North America and work in an intensive care unit with access to state of the art equipment for thermoregulation and also have a team that proudly promotes STS care so is this really needed? Despite all of these concerns the conclusion I have come to is that the technology provides reasonable thermoregulation for a 4-6 hour period. Can this be applied to our patients in the end? I think there may be a role.

I would see the role being in managing newly born infants in remote communities prior to the arrival of a Neonatal Transport Team. In our own centre about 75% of our patients or about 230 patients are transferred from outside of the city borders. On occasion, a premature infant will be born in such places and hypothermia on arrival of the team is not an uncommon occurrence. In Manitoba and many parts of Canada there are communities that are quite isolated from tertiary care centres. These centres have limited equipment and even then it can often be quite outdated if functioning properly at all. Given that the average time to arrival for such infants is less than the 4-6 hours that the mattress provides warmth for, this would seem to be a very beneficial tool to have in such communities. It appears to be the ideal product as the website indicates the following

- Special phase change material in WarmPak maintains a temperature of ~37 °C for at least 4 hours

- Does not require a constant supply of electricity Portable for in-clinic or transport usage

- Reusable and easy to sanitize and reuse

- Enables mother-to-child bonding

As I write this I wonder how many other centres not just in Canada but also in the USA would benefit from looking into such technology. Providing servo controlled infant warmers for each centre that delivers infants is certainly the gold standard and in fact is recommended for all neonates undergoing resuscitation at 10 minutes of age. While ideal we need to acknowledge that some centres do not have such resources so this could very well serve a useful purpose particularly in the Northern US and Canada. According to the Embrace website the concept for this came out of a student project at Stanford University with the goal of designing an infant warmer with a cost of <1% of a traditional infant warmer (about $20000). If the cost is then $200 for the warmer for a completely reusable warming mattress I think they have hit the mark.

Finally, it must be pointed out again that the smallest infants treated in this way have been 1500g. We do not know if smaller infants would remain normothermic or become hypothermic if the same paraffin sized material was utilized. It will be interesting to see if Embrace releases a smaller unit for infants under 1500g. If proven to be successful in maintaining normothermia in this population I believe the use of this device will become widespread. Such a simple concept to treat a big problem in Neonatal Transport!

Looking at the costs for these infants one sees a direct relationship between decreasing birth weight and increasing costs in the hospital. This should not be surprising to anyone. It should be noted though that the paper provides average costs only without standard deviation or ranges. As you would expect, the costs for a patient with severe HIE or NEC would be higher than the 26 week infant who has a very smooth course and does not have a symptomatic PDA, severe IVH or any other significant disability during their course.

Looking at the costs for these infants one sees a direct relationship between decreasing birth weight and increasing costs in the hospital. This should not be surprising to anyone. It should be noted though that the paper provides average costs only without standard deviation or ranges. As you would expect, the costs for a patient with severe HIE or NEC would be higher than the 26 week infant who has a very smooth course and does not have a symptomatic PDA, severe IVH or any other significant disability during their course.

What you will note is that the evaluations for sepsis increased 4X, Respiratory support and intubation almost 2X, with no difference in seizures. It is important to note that the definitions for sepsis were based on two blood cultures being drawn rather than fever alone. Curiously with respect to sepsis there was an increase in the number of positive cultures as well from 2.1 to 3.8% in the evaluations that were done before and after. It is worth pointing out though that I can find no analysis of those results to determine if they were statistically different so at most it is an “interesting” finding.

What you will note is that the evaluations for sepsis increased 4X, Respiratory support and intubation almost 2X, with no difference in seizures. It is important to note that the definitions for sepsis were based on two blood cultures being drawn rather than fever alone. Curiously with respect to sepsis there was an increase in the number of positive cultures as well from 2.1 to 3.8% in the evaluations that were done before and after. It is worth pointing out though that I can find no analysis of those results to determine if they were statistically different so at most it is an “interesting” finding. The steep decline just prior to immunization is known as the Healthy Vaccinee Effect. That is to say that we may see a higher rate of complications simply due to the fact that we wait for kids to be at their healthiest and when they have only had one or two days without apnea or are off their antibiotics that is when we choose to give the vaccine as we believe they can now “handle it”. What we have created is a special sample of patients that actually does not reflect the whole population. What I mean by this is that the response of all patients to their vaccines in this age group might be quite different with no increases in any adverse events if we paid no attention to our preconceived notions that the infant in our care is “too sick” to get their immunization. When we only immunize those kids that are at their best, the likelihood of them deteriorating is higher than when they were “worse”.

The steep decline just prior to immunization is known as the Healthy Vaccinee Effect. That is to say that we may see a higher rate of complications simply due to the fact that we wait for kids to be at their healthiest and when they have only had one or two days without apnea or are off their antibiotics that is when we choose to give the vaccine as we believe they can now “handle it”. What we have created is a special sample of patients that actually does not reflect the whole population. What I mean by this is that the response of all patients to their vaccines in this age group might be quite different with no increases in any adverse events if we paid no attention to our preconceived notions that the infant in our care is “too sick” to get their immunization. When we only immunize those kids that are at their best, the likelihood of them deteriorating is higher than when they were “worse”.

In each case the etiology was found to be the same; estradiol producing ovarian cysts. In one case the cyst was removed and with it the edema resolved and in the other cases progesterone was utilized to suppress production of Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GNRH) and with it production of FSH and LH, thereby reducing the estradiol levels. Ultrasound in each case also revealed uterine enlargement consistent with over stimulation. What is it that causes this phenomenon is unknown for sure but it is certainly curious that the condition only seems to affect preterm infants born at < 29 weeks. Furthermore the timing of the edema is consistently at 36 – 39 weeks CGA. Sedin postulates that the reason for this is that the hypothalamic pituitary axis is immature in these preterm infants and does not provide the negative feedback to reduce LH and FSH compared to the term infant in which such sensitivity is present.

In each case the etiology was found to be the same; estradiol producing ovarian cysts. In one case the cyst was removed and with it the edema resolved and in the other cases progesterone was utilized to suppress production of Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GNRH) and with it production of FSH and LH, thereby reducing the estradiol levels. Ultrasound in each case also revealed uterine enlargement consistent with over stimulation. What is it that causes this phenomenon is unknown for sure but it is certainly curious that the condition only seems to affect preterm infants born at < 29 weeks. Furthermore the timing of the edema is consistently at 36 – 39 weeks CGA. Sedin postulates that the reason for this is that the hypothalamic pituitary axis is immature in these preterm infants and does not provide the negative feedback to reduce LH and FSH compared to the term infant in which such sensitivity is present.