A patient has been extubated to CPAP and is failing with increasing oxygen requirements or increasing apnea and bradycardia. In most cases an infant would be reintubated but is there another way? While CPAP has been around for some time to support our infants after extubation, a new method using high frequency nasal ventilation has arrived and just doesn’t want to go away. Depending on your viewpoint, maybe it should or maybe it is worth a closer look. I have written about the modality before in High Frequency Nasal Ventilation: What Are We Waiting For? While it remains a promising technology questions still remain as to whether it actually delivers as promised.

Better CO2 elimination?

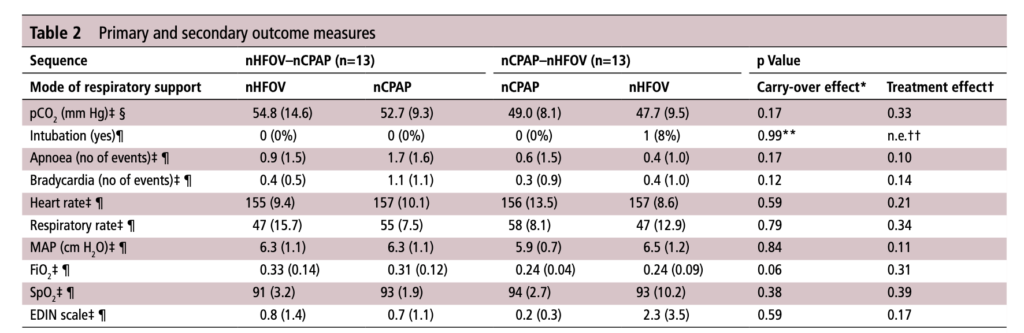

For those who have used a high frequency oscillator, you would know that it does a marvelous job of removing CO2 from the lungs. If it does so well when using an endotracheal tube, why wouldn’t it do just as good a job when used in a non-invasive way? That is the hypothesis that a group of German Neonatologists put forth in their paper this month entitled Non-invasive high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in preterm infants: a randomised controlled crossover trial. In this relatively small study of 26 preterm infants who were all less than 32 weeks at delivery, babies following extubation or less invasive surfactant application were randomized to either receive nHFOV then CPAP for four hours each or the reverse order for the same duration. The primary outcome here was reduction in pCO2 with the goal of seeking a difference of 5% or more in favour of nHFOV. Based on their power calculation they thought they would need 24 infants total and therefore exceeded that number in their enrollment.

The babies in both arms were a bit different which may have confounded the results. The group randomized to CPAP first were larger (mean BW 1083 vs 814g), and there was a much greater proportion of males in the CPAP group. As well, the group randomized first to CPAP had higher baseline O2 saturation of 95% compared to 92% in the nHFOV group. Lastly and perhaps most importantly, there was a much higher rate of capillary blood sampling instead of arterial in the CPAP first group (38% vs 15%). In all cases the numbers are small but when looking for such a small difference in pCO2 and the above mentioned factors tipping the scales one way or the other in terms of illness severity and accuracy of measurement it does give one reason to pause when looking at the results.

The Results

No difference was found in the mean pCO2 from the two groups. As expected, pCO2 obtained from capillary blood gases nearly met significance for being higher than arterial samples (50 vs 47; p=0.052). A similar rate of babies had to drop out of the study (3 on the nCPAP first and 2 on the nHFOV side).

In the end should we really be surprised by the results? I do believe that in the right baby who is about to fail nCPAP a trial of nHFOV may indeed work. By what means I really don’t understand. Is it the fact that the mean airway pressure is generally set higher than on nCPAP in some studies? Could it be the oscillatory vibration being a kind of noxious stimulus that prevents apneic events through irritation of the infant?

While traditional invasive HFOV does a marvelous job of clearing out CO2 I have to wonder how the presence of secretions and a nasopharynx that the oscillatory wave has to avoid (almost like a magic wave that takes a 90 degree turn and then moves down the airway) allows much of any of the wave to reach the distal alveoli. It would be similar to what we know of inhaled steroids being deposited 90 or so percent in the oral cavity and pharynx. There is just a lot of “stuff” in the way from the nostril to the alveolus.

This leads me to my conclusion that if it is pCO2 you are trying to lower, I wouldn’t expect any miracles with nHFOV. Is it totally useless? I don’t think so but for now as a respiratory modality I think for the time being it will continue to be “looking for a place to happen”

We have been trying nHFOV more over the past year. We have moved beyond using it for rescue when NCPAP/NIPPV is failing. We are starting to initiate NIV using nHFOV at times. We have had patients who do better on nHFOV than both NIPPV and nCPAP.

The pressure attenuation through the upper airway with nHFOV is great so it is unlikely that any oscillations pressure amplitude reaches the alveoli. What the oscillations potentially have the benefit to do is very effectively clear CO2 from the upper airway. Could this mean that part of its potential benefit is allowing the patient’s minute ventilation be closer to their alveolar ventilation, decreasing their overall minute ventilation needs?

Knowing that the patient may not actually (nor need) alveolar oscillation to receive potential benefit we don’t focus on the amount of chest wiggle the patient has as we would with invasive HFOV.

I do agree that there are times when using nHFOV that the mean airway pressure (MAWP) is higher than would typically be used with nCPAP or NIPPV and that were some of the benefit may be. It is easier to maintain higher MAWP with nHFOV cause most HOV devices are using bias flows of around 30LPM (does this high bias flow make a difference?).

We are still learning about how nHFOV fits among the respiratory modalities that we have but it has been demonstrated to be safe and well tolerated by the patients.

I believe it was Mark Zarembo that once said, “We don’t do what make us comfortable, we do what makes the patient comfortable.” Having found that some patients seem to well with it, we are getting more comfortable with it and trying it on more patients. Whether or not it is a modality that is superior to others, we will have to wait and see.