by All Things Neonatal | Dec 23, 2015 | hypoglycemia, Uncategorized

The Sugar Babies trial was the subject of a post earlier this year as the largest trial to date examining the effects of using dextrose gel to treat hypoglycemia. For an analysis of the use of gel in this situation please see the original post Glucose Gel For Neonatal Hypoglycemia: Can We Afford Not To Use It?

In summary though, the trial involved 118 infants who received 40% dextrose gel vs 119 who received a placebo gel. All of the infants in this study were selected based on risk factors for hypoglycemia (IDM, IUGR, LBW, LGA, near term) and were all 35 weeks or greater. Each infant had to be less than 48 hours of age when enrolled. Infants received 0.5 mL/kg 40% dextrose gel (200 mg/kg). This was designed to deliver the same amount of sugar as would be given with a D10W bolus of 2 mL/kg. In order to receive the treatment the blood glucose had to be < 2.6 mmol/L so equivalent to our own standards in Canada and the US. Treatment failure, which was the primary outcome was defined as a blood glucose < 2.6 mmol/L despite two treatments with gel. The studies most important findings were a reduction in NICU admission and greater breastfeeding rates at 2 weeks of age (due to avoidance of formula feeding to keep the glucose stable).

But Is It Safe?

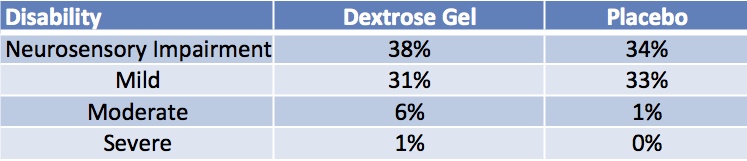

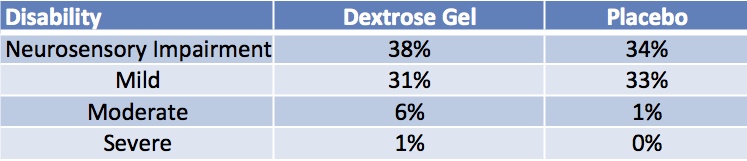

With any new strategy though, questions arise regarding safety of the product in the long term. As one reader commented after the original post, could the red dye be harmful in some way or perhaps some other constituent of the gel? The authors of the original study have now published the follow-up paper entitled Outcome at 2 Years after Dextrose Gel Treatment for Neonatal Hypoglycemia: Follow-Up of a Randomized Trial. The findings were a little concerning to me in that there was a high rate of neurosensory impairment in both arms (sham and glucose gel) with the following findings. None of the differences were significant however.

Looking at these results you could be dismayed that the glucose gel did not show any benefit compared to standard therapies for hypoglycemia but if you look at the original study one could equally ask why would we have expected it to?

Should The Results Surprise Us?

All of the newborns in either arm had an episode of hypoglycemia recorded in order to qualify for entry into the study. The glucose gel was effective compared to placebo in reducing admissions and increasing breastfeeding rates (which one might think would improve outcomes) but we don’t know what the drop off rate in breastfeeding was after 2 weeks. What I can say though is that if there were significant adverse side effects with the glucose gel I would have expected to see some differences in outcome favouring the placebo group which did not occur.

An additional issue is we know that the placebo group had more treatment failures meaning they would have had more newborns in the original study with a second low glucose. Would this favour a worse outcome in the placebo group? If so does the equivalence in groups suggest that the dextrose gel might worsen outcomes?

Unfortunately, what this study is really missing is some indication of how low and how long the blood sugars remained under 2.6 mmol/L in both arms of the study. We know the mean low glucoses were similar but what about duration and range? While the rates of mild, moderate and severe impairment are the same we don’t know how severe the hypoglycemia was which if unbalanced between the groups could actually lead to very different conclusions here. For example, let’s say the glucose gel group had an over representation of infants with 3 or more episodes of hypoglycemia compared to the placebo arm. The fact that the outcomes are equivalent would suggest that the glucose gel is in fact protective.

What Can We Say?

I suspect that while glucose gel is effective, to truly assess harm across many different aspects of development we will need larger sample sizes. We also have to take the results of this study with a grain of salt as so many that have come before it have seen outcomes at school age reveal different findings than when assessed at 2 years of age as in this study. From my standpoint though I will continue to advocate for the use of glucose gel as the reduction in NICU admissions and enhancement of breastfeeding rates especially if sustained are well worth the efforts to implement this strategy if you aren’t using it already.

by All Things Neonatal | Apr 27, 2015 | hypoglycemia, Neonatal

I was inspired to write this post after sharing a review of an article from 2013 on my Facebook page. The article pertained to the use of a 40% dextrose gel to treat neonatal hypoglycemia

We have been using this glucose gel in our population for nearly two years and have noted great success in avoiding admissions for hypoglycemia, however this remains unpublished. I was surprised to hear how many places have yet to adopt such treatment and based on the comments on the page it would appear that adoption of such gels are on their way in some locations. The popularity of this post though inspired me to write this piece, which summarizes the evidence for the use of gels in the neonate.

What is the Evidence For Using Glucose Gels

Surprisingly there is actually very little in the way of publications on the topic. In 1992, there was a small randomized trial which failed to show a benefit in terms of variability of one serum glucose to the next but it did not look at other functional outcomes such as impact on maternal infant separation or success in breast-feeding.

The next study is in fact the one mentioned in the article that was posted on Facebook called the Sugar Babies study. Dr. Harris in this case studied 118 infants who received 40% dextrose gel vs 119 who received a placebo gel. All of the infants in this study were selected based on risk factors for hypoglycemia (IDM, IUGR, LBW, LGA, near term) and were all 35 weeks or greater. Each infant had to be less than 48 hours of age when enrolled. Infants received 0.5 mL/kg 40% dextrose gel (200 mg/kg). This was designed to deliver the same amount of sugar as would be given with a D10W bolus of 2 mL/kg. In order to receive the treatment the blood glucose had to be < 2.6 mmol/L so equivalent to our own standards in Canada and the US. Treatment failure, which was the primary outcome was defined as a blood glucose < 2.6 mmol/L despite two treatments with gel. The significant findings were quite interesting and are shown in the table below.

| Finding |

Dextrose |

Placebo |

| Treatment Failure |

14% |

24% |

| Admission to NICU |

14% |

25% |

| # formula feeds (median) |

7 |

10 |

| Formula fed at 2 weeks |

4% |

13% |

What was not found to be significant and in and of itself is a very important finding is a higher incidence of rebound hypoglycemia in the dextrose gel group. This was a potential concern as provision of dextrose in theory could cause a spike in insulin secretion thereby dramatically lowering the blood glucose but thankfully this was not observed.

Dextrose Gel Improves Breastfeeding Rates

These results I believe speak for themselves but it is extremely important to highlight the benefit here. The use of the dextrose gel was also able to enhance success at breastfeeding rates. This was accomplished in all likelihood by a reduction in admission to NICU and less reliance on formula to achieve satisfactory blood glucose. As these infants were all less than 48 hours old it is safe to assume that in many cases the mother’s milk had not yet come in so if the glucose measured was low, health care providers were more likely to intervene with an offering of formula. It is worth noting that while this is the only significant study in the field there is a letter to the editor in which another author describes the use of a sublingual sugar powder for treating the same, which was met with similar success. There is no actual peer-reviewed study to examine however so we will leave it as simply an interesting point.

New Study on The Way

If these results leave you still being skeptical you may be pleased to hear there is a very large study (2129 babies needed) beginning enrolment in New Zealand with the primary outcome of admission to the NICU. This prospective RCT will hopefully put to rest any questions about this treatment that have delayed implementation in many units.

As a final thought regarding the Sugar Babies study, one of the differences that came close to reaching statistical significance was the rate of IV insertions for dextrose. In the dextrose gel group the rate was 7% vs 14% in the placebo. With a p value of 0.09 it suggests that with a larger study size a difference may have been reached. The idea that we have the option of using a therapy that can decrease formula use, improve breastfeeding rates including those found post discharge and lastly decrease the poking of infants for IV dextrose is a goal well worth pursuing. Is this enough evidence for you? I would encourage all who read this piece to ask their NICU the question of whether a trial of dextrose gel is worthwhile. It could make a big difference far beyond treating a number.