by All Things Neonatal | Jul 9, 2018 | hemodynamics

Welcome to the home page for our Integrated Evaluation of Hemodynamics program at the University of Manitoba. This program began in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada in 2014 and has been growing ever since.

What is considered normal hemodynamics?

1. Intact or normal hemodynamics implies blood flow that provides adequate oxygen and nutrient delivery to the tissues.

2. Blood flow varies with vascular resistance and cardiac function; both may be reflected in blood pressure(2). Normal cardiovascular dynamics should be considered within the context of global hemodynamic function, with the aim of achieving normal oxygen delivery and end organ performance

3. The current routine assessment of hemodynamics in sick preterm and term infants is based on incomplete information. We have addressed this by adopting an approach utilizing objective techniques, namely integrating targeted neonatal echocardiography (TNE) with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). Implementation of these techniques requires an individual with the requisite TNE training, preferably in an accredited program, who also has a good understanding of perinatal and neonatal cardiovascular, respiratory, and other specific end organ physiology.

Why are premature infants more susceptible to cardiovascular compromise?

Hemodynamic compromise in the early neonatal period is common and may lead to unfavorable neurodevelopmental outcome4. A thorough understanding of the physiology of the cardiovascular system in the preterm infants, influence of antenatal factors, and postnatal adaptation is essential for the management of these infants during the early critical phase5. The impact of the various ventilator modes, the presence of a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and systemic inflammation all may affect the hemodynamics6. The poor clinical indicators of systemic perfusion and the relative insensitivity of conventional echocardiographic techniques in assessing myocardial contractility mean that monitoring of the hemodynamics of the preterm infant remains a challenge7.

What is integrated hemodynamics in neonatal care?

Integrated hemodynamics focuses on how to interpret multiple tools of hemodynamics evaluation in sick infants (TNE, clinical details, NIRS, organ specific ultrasound) and the art of formulating a pathophysiologic relevant medical recommendation.

Main objectives of applying Targeted Neonatal Echocardiography and Evaluation of Neonatal hemodynamics

Optimise care of infants with hemodynamic compromise to prevent progression into late irreversible stages of shock (Hypoxia)

Decrease overall PDA related complications (Hypoxemia and hypoxia)

Optimize care of infants with hypoxemic respiratory failure (HRF)

Decrease the incidence of progression of infants with hypoxemic respiratory failure and shock to end organ dysfunction

Objective of the program

Orientation to the hemodynamics concepts and basics

Orientation to the 3 level of the pathophysiologic approach to hemodynamics:

Level one: Relying on blood pressure trends (systole, diastole, and pulse pressure) and waveforms with other clinical parameters (all NICU practitioners)

Level one plus (advanced monitoring): Relying on blood pressure trend and near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for assessment of hemodynamics and oxygen extraction (optional to NICU practitioners)

Level two (TNE approach): Relying on both clinical parameters and TNE for objective assessment of cardiac output, extra and intra cardiac shunts, systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance. (Neonatologist trained on TNE)

Level three (integrated evaluation of hemodynamics): integrating blood pressure trends, TNE and NIRS for assessment of oxygen delivery, specific end organ oxygen consumption and the degree of compensation (comprehensive hemodynamic approach)

Understanding the rationale for the measurements and the specific values for each disease, and recognize limitations of the 3 models

To see research that we have done in the area of Integrated Hemodynamics please see our publication list that can be found here.

To access our video series providing examples of TNE and presentations on the use of hemodynamics in clinical application please see our Youtube channel playlist “Integrated Neonatal Hemodynamics”

References

Wolff CB. Normal cardiac output, oxygen delivery and oxygen extraction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;599:169-182. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-71764-7-23.

Azhan A, Wong FY. Challenges in understanding the impact of blood pressure management on cerebral oxygenation in the preterm brain. Front Physiol. 2012;3 DEC(December):1-8. doi:10.3389/fphys.2012.00471.

de Boode WP. Clinical monitoring of systemic hemodynamics in critically ill newborns. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(3):137-141. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.031.

Sehgal A. Haemodynamically unstable preterm infant: an unresolved management conundrum. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(10):1237-1245. doi:10.1007/s00431-011-1435-4.

Vutskits L. Cerebral blood flow in the neonate. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24(2):22-29. doi:10.1111/pan.12307.

Noori S, Stavroudis T a, Seri I. Systemic and cerebral hemodynamics during the transitional period after premature birth. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36(4):723-36, v. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2009.07.015.

Elsayed YN, Amer R, Seshia MM. The impact of integrated evaluation of hemodynamics using targeted neonatal echocardiography with indices of tissue oxygenation: a new approach. J Perinatol. 2017. doi:10.1038/jp.2016.257.

by All Things Neonatal | Jun 30, 2018 | intubation, Neonatal, Neonatology, newborn, preemie, Prematurity

A few weeks back I wrote about the topic of intubations and whether premedication is really needed (Still performing awake intubations in newborns? Maybe this will change your mind.) I was clear in my belief that it is and offered reasons why. There is another group of practitioners though that generally agree that premedication is beneficial but have a different question. Many believe that analgesia or sedation is needed but question the need for paralysis. The usual argument is that if the intubation doesn’t go well and the patient can’t spontaneously ventilate could we be worse off if the patient loses their muscle tone.

Neonatal Intubation Registry

At the CPS meeting last month in Quebec City. I had the pleasure of listening to a talk by Dr. Elizabeth Foglia on the findings from a Neonatal intubation registry that many centres have been contributing to. The National Emergency Airway Registry for Neonates (NEAR4NEOs), records all intubations from a number of centres using an online database and allows for analysis of many different aspects of intubations in neonates.

This year, J. Krick et al published Premedication with paralysis improves intubation success and decreases adverse events in very low birth weight infants: a prospective cohort study. This study compared results from the registry of two centres, the University of Washington Medical Center (UWMC) and Seattle Children’s Hospital where the former rarely uses paralysis and the latter in almost all instances of non-emergent intubation. In all, 237 encounters were analyzed in the NICU for babies < 1500g with the majority of encounters (181) being from UWMC. The median PMA at intubation was 28 completed weeks (IQR: 27, 30), chronological age was 9 days (IQR: 2, 26) and weight was 953 g (IQR: 742,1200). The babies were compared based on the following groups. Premedication with a paralytic 21%, without a paralytic 46% and no premedication 31%.

This was an observational study that examined the rates of adverse events and subdivided into severe (cardiac arrest, esophageal intubation with delayed recognition, emesis with witnessed aspiration, hypotension requiring intervention (fluid and/or vasopressors), laryngospasm, malignant hyperthermia, pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum, or direct airway injury) vs non-severe (mainstem bronchial intuba- tion, esophageal intubation with immediate recognition, emesis without aspiration, hypertension requiring therapy, epistaxis, lip trauma, gum or oral trauma, dysrhythmia, and pain and/or agitation requiring additional medication and causing a delay in intubation.).

How did the groups compare?

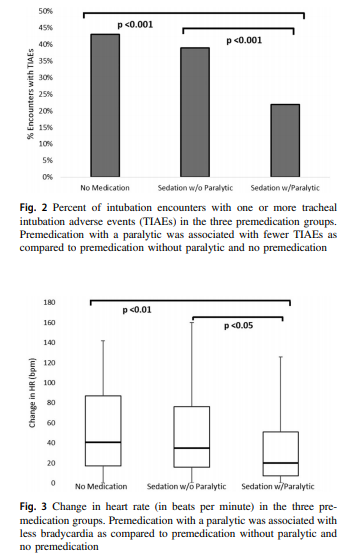

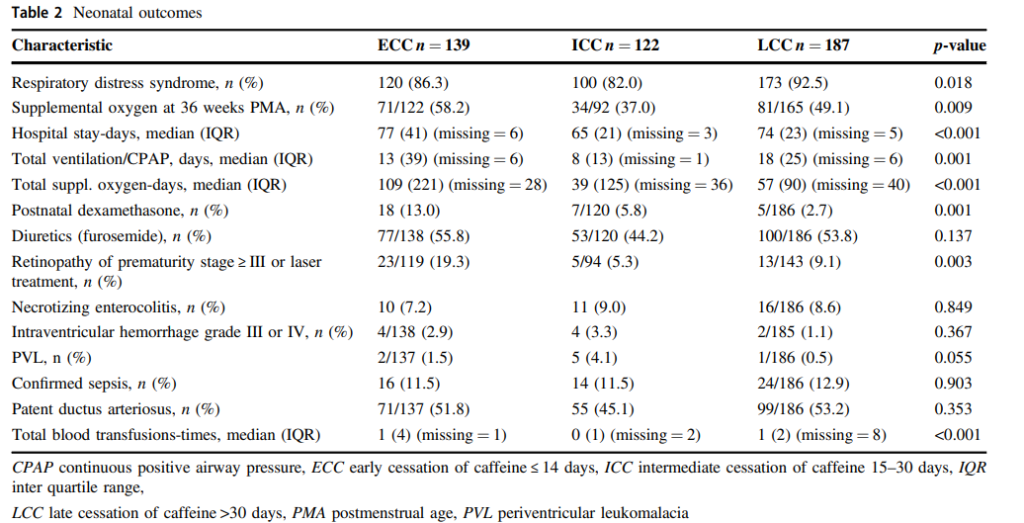

It turns out paralysis seems to be a big deal (at least in this group of infants). Use of paralysis resulted in less attempts to intubate (median 1 attempt; IQR: 1, 2.25 vs. 2; IQR: 1, 3, p < 0.05)). In fact success was no different between the groups with no paralysis or no premedication at all! When it comes to tracheal intubation adverse events the impact of using paralysis becomes more evident.

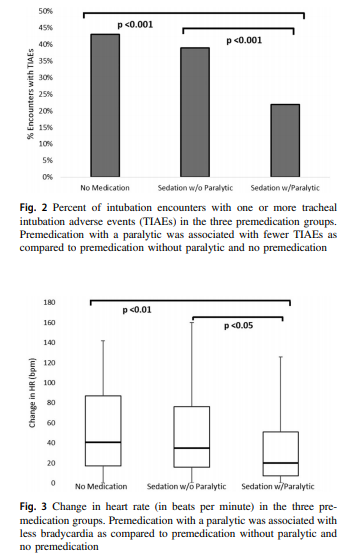

Paralysis does make a difference in reducing the incidence of such events and moreover when only looking at the rate of severe adverse events as defined above the finding was that none occurred when paralysis was used vs 9 when no paralysis was employed and 5 when no premedication was used at all. The rate of bradycardic events was less in the paralytic group but rates of oxygen desaturation between the three arms were no different.

Paralysis does make a difference in reducing the incidence of such events and moreover when only looking at the rate of severe adverse events as defined above the finding was that none occurred when paralysis was used vs 9 when no paralysis was employed and 5 when no premedication was used at all. The rate of bradycardic events was less in the paralytic group but rates of oxygen desaturation between the three arms were no different.

How do we interpret the results?

Based on the results from the registry it looks like paralysis is a good thing here when electively intubating infants. If we try to determine the reason for it I suspect it may have much to do with the higher likelihood of success on the first attempt at placing an ETT. The longer it takes to place the ETT or the more number of attempts requiring intermittent PPV in a patient who truly needs a tube the greater the likelihood that you will see adverse events including bradycardia. It may simply be that a calm and still patient is an easier intubation and getting the tube in faster yields a more stable patient.

I am biased though and I think it is worth pointing out another possible reason for the differing results. One hospital in this study routinely used premedication and the other did not. Almost 3/4 of the patients came from one hospital which raises the possibility that skill set could be playing a role. If the skill of providers at the two hospitals differed, the results could reflect the variable skill in the practitioners versus the difference in the medications used themselves. What I don’t know though is whether the two share the same training program or not. Are the trainees the same at both sites (google maps says the two sites are 11 minutes away by car)? The difference still might be in local respiratory therapists or Neonatologists intubating as well. Regardless, the study provides evidence that paralysis makes a difference. To convince those out there though who remain skeptical I think we are going to need the registry to take part in a prospective trial using many centres. A format in which several centres that don’t use paralysis are compared to several who do routinely would help to sort out the concern in skill when looking only at two centres. This wouldn’t be randomized of course but I think it would be very difficult at this point to get a centre that strongly believes in using paralysis to randomize so a prospective study using groups chosen by the individual centre might be the next best thing. If anyone using the registry is reading this let me know what you think?

by All Things Neonatal | Jun 27, 2018 | NAS, Neonatal, neonatal abstinence, Neonatology

This post is very timely as the CPS Fetus and Newborn committee has just released a new practice point:

This post is very timely as the CPS Fetus and Newborn committee has just released a new practice point:

Managing infants born to mothers who have used opioids during pregnancy

Have a look at discharge considerations as that section in the statement speaks to this topic as well!

As bed pressures mount seemingly everywhere and “patient flow” becomes the catch-word of the day, wouldn’t it be nice to manage NAS patients in their homes? In many centres, such patients if hospitalized can take up to 3 weeks on average to discharge home off medications. Although done sporadically in our own centre, the question remains is one approach better than the another? Nothing is ever simple though and no doubt there are many factors to consider depending on where you live and what resources are available to you. Do you have outpatient follow-up at your disposal with practitioners well versed in the symptoms of NAS and moreover know what to do about them? Is there comfort in the first place with sending babies home on an opioid or phenobarbital with potential side effects of sedation and poor feeding? Nonetheless, the temptation to shift therapy from an inpatient to outpatient approach is very tempting.

The Tennessee Experience

Maalouf Fl et al have published an interesting account of the experience with outpatient therapy in their paper Outpatient Pharmacotherapy for Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. The authors were able to take advantage of the Tennessee Medicaid program using administrative

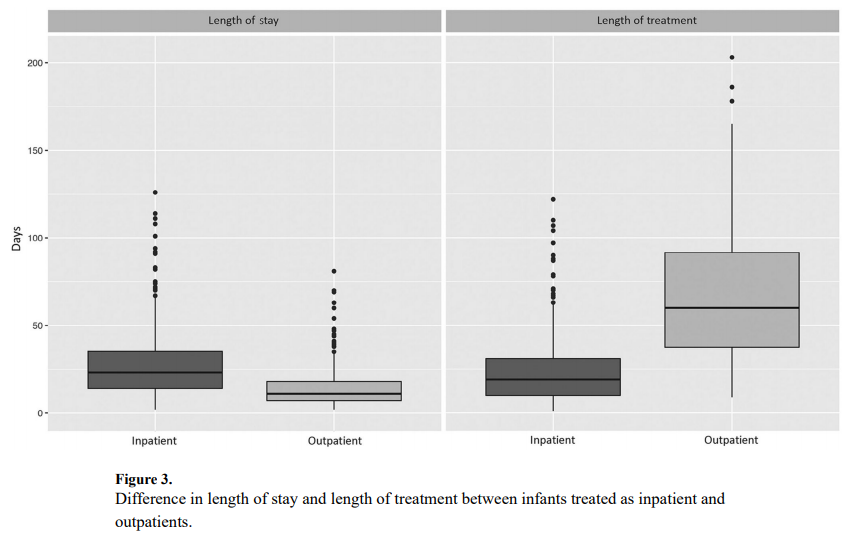

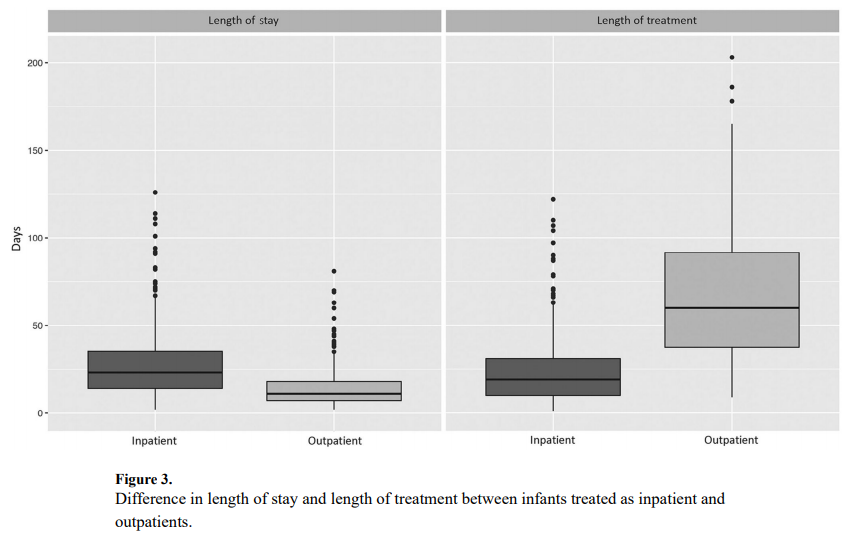

and vital records data from 2009 to 2011 to capture a cohort of 736 patients who were treated for NAS. Forty five percent or 242 patients were treated as outpatients vs 290 cared for in hospital for the duration of treatment. It is worth mentioning at this point that when the authors say they were cared for as outpatients it really is a hybrid model as the duration of hospitalization for the inpatients was a median of 23 days (IQR 14-35) versus 11 days (IQR 7-18) for inpatients (P < .001). This practice isn’t much different than my own in which I start therapy in hospital and then discharge home with a period of home therapy.

The strength of the study is the volume of patients and the ability to follow-up with these babies for the first 6 months of life to determine what happened to them after discharge. In terms of duration of treatment, the differences are significant but perhaps not surprising. The median length of treatment for outpatients was 60 days (IQR 38-92) compared with 19 days (IQR 10-31) for inpatients (P < .001). What was interesting as well is that 82% of babies were discharged home on phenobarbital and 9.1% on methadone and 7.4% with both. A very small minority was discharged home on something else such as morphine or clonidine. That there was a tripling of medication wean is not surprising as once the patients are out of the watchful eye of the medical team in hospital it is likely that practitioners would use a very slow wean out of hospital to minimize the risk of withdrawal.

An Unintended Consequence

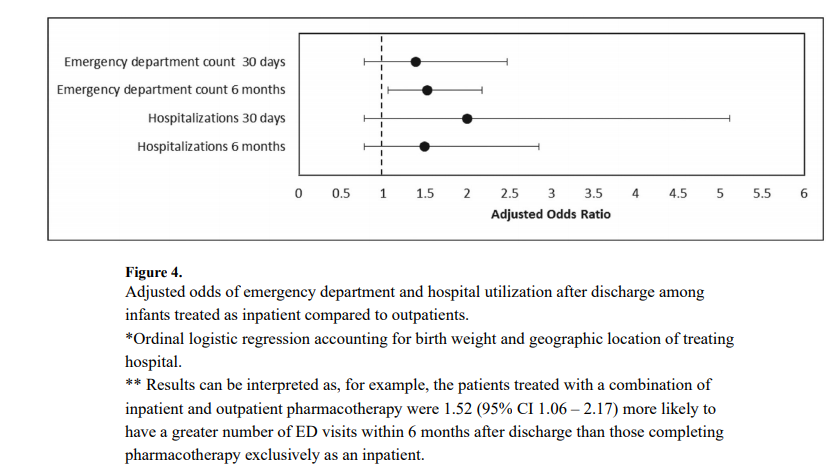

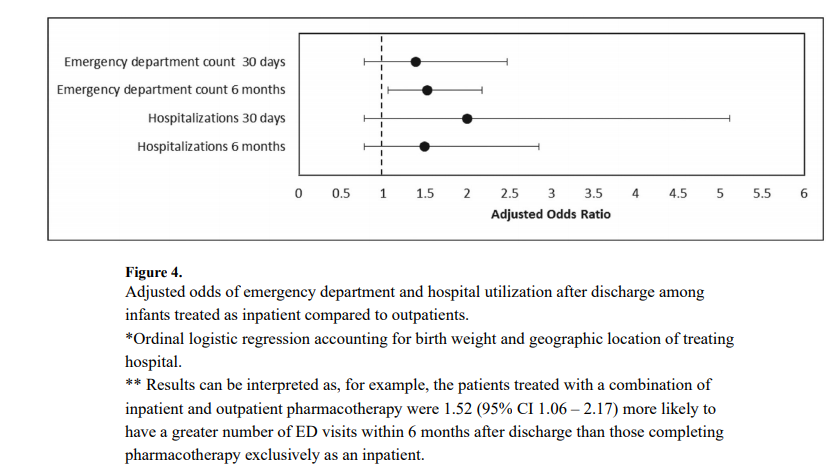

This study found a statistically significant increase in risk for presenting to the emergency department for those patients treated as outpatients.

What this graph demonstrates is that there was no increase risk in the first month but there was for the first 6 months. Despite the increased risk of presentation to the ED the rate of hospitalization was not different. Drilling down the data further, the reason for coming to the ED was not for withdrawal which was 10% in the outpatient and 11% in the inpatient group. The other major reason was The most common diagnoses were upper respiratory infections; 80% outpatient vs 71% inpatient. So while there was a significant difference (which was not by much) my take on it is that it was most likely by chance as I can’t think of how infections in the first 6 months could be linked to choice of medication wean.

What about phenobarbital?

Phenobarbital has been used for many years in Neonatology for control of seizures, sedation (taking advantage of a side effect) and management of NAS. The problem with a median use of phenobarbital for 2 months is its potential to affect development.

An animal study by Diaz in 1999 in which rat pups were given two weeks of phenobarbital starting on day 5 of life and then euthanized demonstrated the following weight reductions when high dose phenobarbital was utilized. In human data, children with febrile seizures treated with phenobarbital in the paper Late cognitive effects of early treatment with phenobarbital. had decreased intelligence than those not exposed to phenobarbital.

The issue here for me is not necessarily whether babies can be treated successfully as outpatients for NAS. The concern is at what cost if the choice of drug is phenobarbital. The reason phenobarbital was chosen is likely due to compliance. We know that the more frequently a drug is dose the less likely compliance will be achieved. Phenobarbital being dosed either q12h or q24h is an ideal drug from a compliance point of view but the ramifications of this treatment deserve reconsideration.

I look forward to seeing further studies on this topic and hope that we see the results of an opioid outpatient treatment program. I know these exist and would welcome any information you as the readers of this blog can offer. Treating patients in the home makes great sense to me but we need to do it with the right drugs!

by All Things Neonatal | Jun 20, 2018 | apnea of prematurity, BPD, caffeine

Much has been written about methylxanthines over the years with the main questions initially being, “should we use them?”, “how big a dose should we use” and of course “theophylline vs caffeine”. At least in our units and in most others I know of caffeine seems to reign supreme and while there remains some discussion about whether dosing for maintenance of 2.5 -5 mg/kg/d of caffeine base or 5 – 10 mg/kg/d is the right way to go I think most favour the lower dose. We also know from the CAP study that not only does caffeine work to treat apnea of prematurity but it also appears to reduce the risk of BPD, PDA and duration of oxygen therapy to name a few benefits. Although initially promising as providing a benefit by improving neurodevelopmental outcomes in those who received it, by 5 and 11 years these benefits seem to disappear with only mild motor differences being seen.

Much has been written about methylxanthines over the years with the main questions initially being, “should we use them?”, “how big a dose should we use” and of course “theophylline vs caffeine”. At least in our units and in most others I know of caffeine seems to reign supreme and while there remains some discussion about whether dosing for maintenance of 2.5 -5 mg/kg/d of caffeine base or 5 – 10 mg/kg/d is the right way to go I think most favour the lower dose. We also know from the CAP study that not only does caffeine work to treat apnea of prematurity but it also appears to reduce the risk of BPD, PDA and duration of oxygen therapy to name a few benefits. Although initially promising as providing a benefit by improving neurodevelopmental outcomes in those who received it, by 5 and 11 years these benefits seem to disappear with only mild motor differences being seen.

Turning to a new question

The new query though is how long to treat? Many units will typically stop caffeine somewhere between 33-35 weeks PMA on the grounds that most babies by then should have outgrown their irregular respiration patterns and have enough pulmonary reserve to withstand a little periodic breathing. Certainly there are those who prove that they truly still need their caffeine and on occasion I have sent some babies home with caffeine when they are fully fed and otherwise able to go home but just can’t seem to stabilize their breathing enough to be off a monitor without caffeine. Then there is also more recent data suggesting that due to intermittent hypoxic episodes in the smallest of infants at term equivalent age, a longer duration of therapy might be advisable for these ELBWs. What really hasn’t been looked at well though is what duration of caffeine might be associated with the best neurodevelopmental outcomes. While I would love to see a prospective study to tackle this question for now we will have to do with one that while retrospective does an admirable job of searching for an answer.

The Calgary Neonatal Group May Have The Answer

Lodha A et al recently published the paper Does duration of caffeine therapy in preterm infants born ≤1250 g at birth influence neurodevelopmental (ND) outcomes at 3 years of

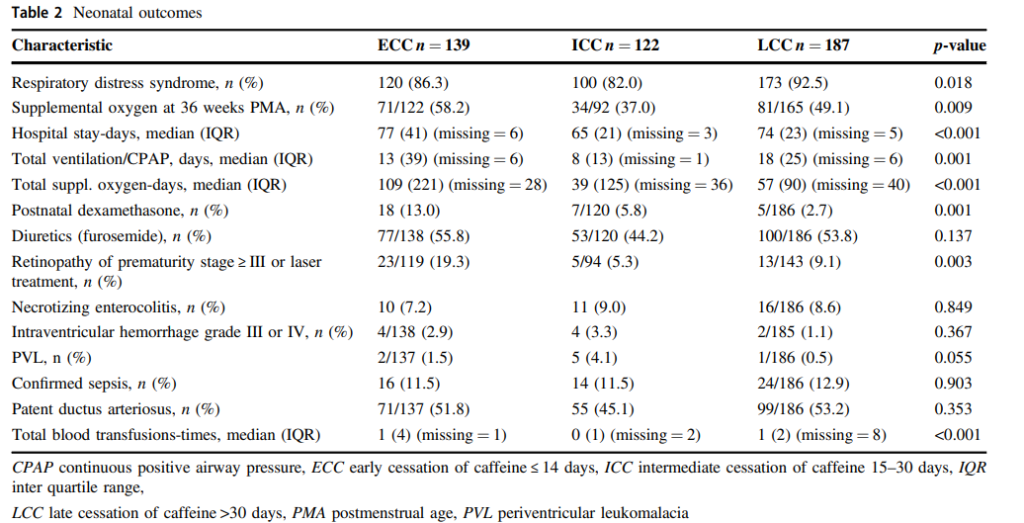

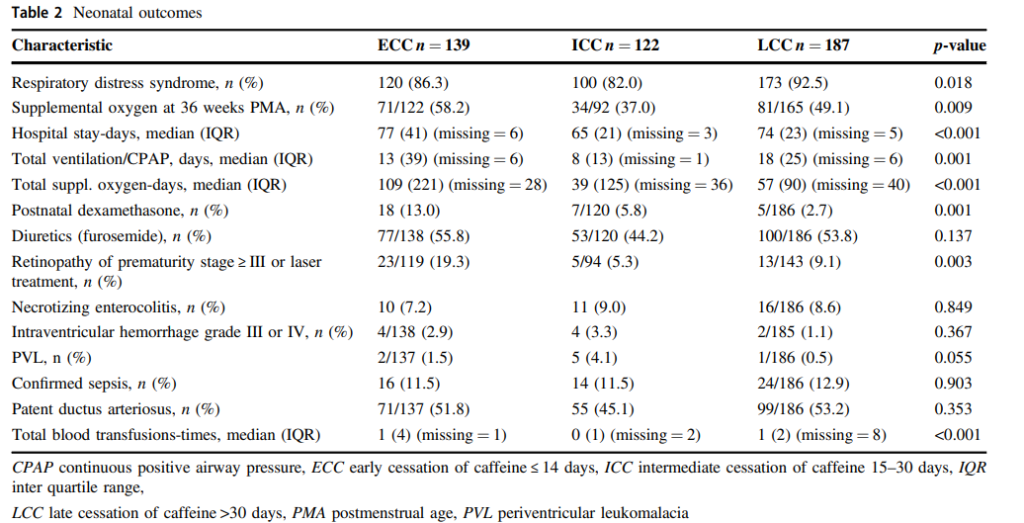

age? This retrospective study looked at infants under 1250g at birth who were treated within one week of age with caffeine and divided them into three categories based on duration of caffeine therapy. The groups were as follows, early cessation of caffeine ≤ 14 days (ECC), intermediate cessation of caffeine 15–30 days (ICC), and late cessation of

caffeine >30 days (LCC). In total there were 508 eligible infants with 448 (88%) seen at 3 years CA at follow-up. ECC (n = 139), ICC (n = 122) and LCC (n = 187). The primary outcome here was ND at 3 years of age while a host of secondary outcomes were also examined such as RDS, PDA, BPD, ROP as typical morbidities. It made sense to look at these since provision of caffeine had previously been shown to modify such outcomes.

Did they find a benefit?

Sadly there did not appear to be any benefit regardless of which group infants fell in with respect to duration of caffeine when it came to ND. When looking at secondary

When looking at secondary  outcomes there were a few key differences found which favoured the ICC group. These infants had the lowest days of supplemental oxygen, hospital stay ROP and total days of ventilation. This middle group also had a median GA 1 week older at 27 weeks than the other two groups. The authors however did a logistic regression and ruled out the improvement based on the advanced GA. The group with the lowest use of caffeine had higher number of days on supplemental oxygen and higher days of ventilation on average than the middle but not the high caffeine group. It is tempting to blame the result for the longer caffeine group on these being babies that were just sicker and therefore needed caffeine longer. On the other hand the babies that were treated with caffeine for less than two weeks appear to have likely needed it longer as they needed longer durations of oxygen and were ventilated longer so perhaps were under treated. What is fair to say though is that the short and long groups having longer median days of ventilation were more likey to have morbidities associated with that being worse ROP and need for O2. In short they likely had more lung damage. What is really puzzling to me is that with a median GA of 27-28 weeks some of these kids were off caffeine before 30 weeks PMA and in the middle group for the most part before 32 weeks! If they were in need of O2 and ventilation for at least two weeks maybe they needed more caffeine or perhaps the babies in these groups were just less sick?

outcomes there were a few key differences found which favoured the ICC group. These infants had the lowest days of supplemental oxygen, hospital stay ROP and total days of ventilation. This middle group also had a median GA 1 week older at 27 weeks than the other two groups. The authors however did a logistic regression and ruled out the improvement based on the advanced GA. The group with the lowest use of caffeine had higher number of days on supplemental oxygen and higher days of ventilation on average than the middle but not the high caffeine group. It is tempting to blame the result for the longer caffeine group on these being babies that were just sicker and therefore needed caffeine longer. On the other hand the babies that were treated with caffeine for less than two weeks appear to have likely needed it longer as they needed longer durations of oxygen and were ventilated longer so perhaps were under treated. What is fair to say though is that the short and long groups having longer median days of ventilation were more likey to have morbidities associated with that being worse ROP and need for O2. In short they likely had more lung damage. What is really puzzling to me is that with a median GA of 27-28 weeks some of these kids were off caffeine before 30 weeks PMA and in the middle group for the most part before 32 weeks! If they were in need of O2 and ventilation for at least two weeks maybe they needed more caffeine or perhaps the babies in these groups were just less sick?

What is missing?

There is another potential answer to why the middle group did the best. In the methods section the authors acknowledge that for each infant caffeine was loaded at 10 mg/kg/d. What we don’t know though is what the cumulative dose was for the different groups. The range of dosing was from 2.5-5 mg/kg/d for maintenance. Lets say there was an over representation of babies on 2.5 mg/kg/d in the short and long duration groups compared to the middle group. Could this actually be the reason behind the difference in outcomes? If for example the dosing on average was lower in these two groups might it be that with less respiratory drive the babies in those groups needed faster ventilator rates with longer durations of support leading to more lung damage and with it the rest of the morbidities that followed?

It would be interesting to see such data to determine if the two groups were indeed dosed on average lower by looking at median doses and total cumulative doses including miniloads along the way. We know that duration may need to be prolonged in some patients but we also know that dose matters and without knowing this piece of information it is tough to come to a conclusion about how long exactly to treat.

What this study does though is beg for a prospective study to determine when one should stop caffeine as that answer eludes us!

by All Things Neonatal | May 30, 2018 | intubation, Neonatal, Neonatology, preemie, Prematurity, resuscitation

If I look back on my career there have been many things I have been passionate about but the one that sticks out as the most longstanding is premedicating newborns prior to non-emergent intubation. The bolded words in the last sentence are meant to reinforce that in the setting of a newborn who is deteriorating rapidly it would be inappropriate to wait for medications to be drawn up if the infant is already experiencing severe oxygen desaturation and/or bradycardia. The CPS Fetus and Newborn committee of which I am a member has a statement on the use of premedication which seems as relevant today as when it was first developed. In this statement the suggested cocktail of atropine, fentanyl and succinylcholine is recommended and having used it in our centre I can confirm that it is effective. In spite of this recommendation by our national organization there remain those who are skeptical of the need for this altogether and then there are others who continue to search for a better cocktail. Since I am at the annual conference for the CPS in Quebec city  I thought it would be appropriate to provide a few comments on this topic.

I thought it would be appropriate to provide a few comments on this topic.

Three concerns with rapid sequence induction (RSI) for premedication before intubation

1. “I don’t need it. I don’t have any trouble intubating a newborn” – This is perhaps the most common reason I hear naysayers raise. There is no question that an 60-90 kg practitioner can overpower a < 5kg infant and in particular an ELBW infant weighing < 1 kg. This misses the point though. Premedicating has been shown to increase success on the first attempt and shorten times to intubation. Dempsey 2006, Roberts 2006, Carbajal 2007, Lemyre 2009

2. “I usually get in on the first attempt and am very slick so risk of injury is less.” Not really true overall. No doubt there are those individuals who are highly successful but overall the risk of adverse events is reduced with premedication. (Marshall 1984, Lemyre 2009). I would also proudly add another Canadian study from Edmonton by Dr. Byrne and Dr. Barrington who performed 249 consecutive intubations with predication and noted minimal side effects but high success rates at first pass.

3. “Intubation is not a painful procedure”. This one is somewhat tough to obtain a true answer for as the neonate of course cannot speak to this. There is evidence available again from Canadian colleagues in 1984 and 1989 that would suggest that infants at the very least experience discomfort or show physiologic signs of stress when intubated using an “awake” approach. In 1984 Kelly and Finer in Edmonton published Nasotracheal intubation in the neonate: physiologic responses and effects of atropine and pancuronium. This randomized study of atropine with or without pancuronium vs control demonstrated intracranial hypertension only in those infants in the control arm with premedication ameliorating this finding. Similarly, in 1989 Barrington, Finer and the late Phil Etches also in Edmonton published Succinylcholine and atropine for premedication of the newborn infant before nasotracheal intubation: a randomized, controlled trial. This small study of 20 infants demonstrated the same finding of elimination of intracranial hypertension with premedication. At the very least I would suggest that having a laryngoscope blade put in your oral cavity while awake must be uncomfortable. If you still doubt that statement ask yourself whether you would want sedation if you needed to be intubated? Still feel the same way about babies not needing any?

4. What if I sedate and paralyze and there is a critical airway? Well this one may be something to consider. If one knows there is a large mass such as a cystic hygroma it may be best to leave the sedation or at least the paralysis out. The concern though that there might be an internal mass or obstruction that we just don’t know about seems a little unfounded as a justification for avoiding medications though.

Do we have the right cocktail?

The short answer is “I don’t know”. What I do know is that the use of atropine, an opioid and a muscle relaxant seems to provide good conditions for intubating newborns. We are in the era of refinement though and as a recent paper suggests, there could be alternatives to consider;Effect of Atropine With Propofol vs Atropine With Atracurium and Sufentanil on Oxygen Desaturation in Neonates Requiring Nonemergency IntubationA Randomized Clinical Trial. I personally like the idea of a two drug combination for intubating vs.. three as it leaves one less drug to worry about a medication error with. There are many papers out there looking at different drug combinations. This one though didn’t find a difference between the two combinations in terms of prolonged desaturations between the two groups which was the primary outcome. Interestingly though the process of intubating was longer with atropine and propofol. Given some peoples reluctance to use RSI at all, any drug combination which adds time to the the procedure is unlikely to go over well. Stay tuned though as I am sure there will be many other combinations over the next few years to try out!

Paralysis does make a difference in reducing the incidence of such events and moreover when only looking at the rate of severe adverse events as defined above the finding was that none occurred when paralysis was used vs 9 when no paralysis was employed and 5 when no premedication was used at all. The rate of bradycardic events was less in the paralytic group but rates of oxygen desaturation between the three arms were no different.

Paralysis does make a difference in reducing the incidence of such events and moreover when only looking at the rate of severe adverse events as defined above the finding was that none occurred when paralysis was used vs 9 when no paralysis was employed and 5 when no premedication was used at all. The rate of bradycardic events was less in the paralytic group but rates of oxygen desaturation between the three arms were no different.

This post is very timely as the CPS Fetus and Newborn committee has just released a new practice point:

This post is very timely as the CPS Fetus and Newborn committee has just released a new practice point:

Much has been written about methylxanthines over the years with the main questions initially being, “should we use them?”, “how big a dose should we use” and of course “theophylline vs caffeine”. At least in our units and in most others I know of caffeine seems to reign supreme and while there remains some discussion about whether dosing for maintenance of 2.5 -5 mg/kg/d of caffeine base or 5 – 10 mg/kg/d is the right way to go I think most favour the lower dose. We also know from the CAP study that not only does caffeine work to treat apnea of prematurity but it also appears to reduce the risk of BPD, PDA and duration of oxygen therapy to name a few benefits. Although initially promising as providing a benefit by improving neurodevelopmental outcomes in those who received it, by 5 and 11 years these benefits seem to disappear with only mild motor differences being seen.

Much has been written about methylxanthines over the years with the main questions initially being, “should we use them?”, “how big a dose should we use” and of course “theophylline vs caffeine”. At least in our units and in most others I know of caffeine seems to reign supreme and while there remains some discussion about whether dosing for maintenance of 2.5 -5 mg/kg/d of caffeine base or 5 – 10 mg/kg/d is the right way to go I think most favour the lower dose. We also know from the CAP study that not only does caffeine work to treat apnea of prematurity but it also appears to reduce the risk of BPD, PDA and duration of oxygen therapy to name a few benefits. Although initially promising as providing a benefit by improving neurodevelopmental outcomes in those who received it, by 5 and 11 years these benefits seem to disappear with only mild motor differences being seen. When looking at secondary

When looking at secondary

I thought it would be appropriate to provide a few comments on this topic.

I thought it would be appropriate to provide a few comments on this topic.