by All Things Neonatal | Sep 28, 2017 | caffeine, preemie, Prematurity

Given that many preterm infants as they near term equivalent age are ready to go home it is common practice to discontinue caffeine sometime between 33-34 weeks PMA. We do this as we try to time the readiness for discharge in terms of feeding, to the desire to see how infants fare off caffeine. In general, most units I believe try to send babies home without caffeine so we do our best to judge the right timing in stopping this medication. After a period of 5-7 days we generally declare the infant safe to be off caffeine and then move on to other issues preventing them from going home to their families. This strategy generally works well for those infants who are born at later gestations but as Rhein LM et al demonstrated in their paper Effects of caffeine on intermittent hypoxia in infants born prematurely: a randomized clinical trial., after caffeine is stopped, the number of intermittent hypoxic (IH) events are not trivial between 35-39 weeks. Caffeine it would seem may still offer some benefit to those infants who seem otherwise ready to discontinue the medication. What the authors noted in this randomized controlled trial was that the difference caffeine made when continued past 34 weeks was limited to reducing these IH events only from 35-36 weeks but the effect didn’t last past that. Why might that have been? Well it could be that the babies after 36 weeks don’t have enough events to really show a difference or it could be that the dose of caffeine isn’t enough by that point. The latter may well be the case as the metabolism of caffeine ramps up during later gestations and changes from a half life greater than a day in the smallest infants to many hours closer to term. Maybe the caffeine just clears faster?

Follow-up Study attempts to answer that very question.

Recognizing the possibility that levels of caffeine were falling too low after 36 weeks the authors of the previous study begun anew to ask the same question but this time looking at caffeine levels in saliva to ensure that sufficient levels were obtained to demonstrate a difference in the outcome of frequency of IH. In this study, they compared the original cohort of patients who did not receive caffeine after planned discontinuation (N=53) to 27 infants who were randomized to one of two caffeine treatments once the decision to stop caffeine was made. Until 36 weeks PMA each patient was given a standard 10 mg/kg of caffeine case and then randomized to two different strategies. The two dosing strategies were 14 mg/kg of caffeine citrate (equals 7 mg/kg of caffeine base) vs 20 mg/kg (10 mg/kg caffeine base) which both started once the patient reached 36 weeks in anticipation of increased clearance. Salivary caffeine levels were measured just prior to stopping the usual dose of caffeine and then one week after starting 10 mg/kg dosing and then at 37 and 38 weeks respectively on the higher dosing. Adequate serum levels are understood to be > 20 mcg/ml and salivary and plasma concentrations have been shown to have a high level of agreement previously so salivary measurement seems like a good approach. Given that it was a small study it is work noting that the average age of the group that did not receive caffeine was 29.1 weeks compared to the caffeine groups at 27.9 weeks. This becomes important in the context of the results in that earlier gestational age patients would be expected to have more apnea which is not what was observed suggesting a beneficial effect of caffeine even at this later gestational age. Each patient was to be monitored with an oximeter until 40 weeks as per unit guidelines.

So does caffeine make a difference once term gestation is reached?

A total of 32 infants were enrolled with 12 infants receiving the 14 mg/kg and 14 the 20 mg/kg dosing. All infants irrespective of assigned group had caffeine concentrations above 20 mcg/mL ensuring that a therapeutic dose had been received. The intent had been to look at babies out to 40 weeks with pulse oximetry even when discharged but owing to drop off in compliance with monitoring for a minimum of 10 hours per PMA week the analysis was restricted to infants at 37 and 38 weeks which still meant extension past 36 weeks as had been looked at already in the previous study. The design of this study then compared infants receiving known therapeutic dosing at this GA range with a previous cohort from the last study that did not receive caffeine after clinicians had determined it was no longer needed.

The outcomes here were measured in seconds per 24 hours of intermittent hypoxia (An IH event was defined as a decrease in SaO2 by ⩾ 10% from baseline and lasting for ⩾5 s). For graphical purposes the authors chose to display the number of seconds oxygen saturation fell below 90% per day and grouped the two caffeine patients together given that the salivary levels in both were therapeutic. As shown a significant difference in events was seen at all gestational ages.

Putting it into context

The scale used I find interesting and I can’t help but wonder if it was done intentionally to provide impact. The outcome here is measured in seconds and when you are speaking about a mean of 1200 vs 600 seconds it sounds very dramatic but changing that into minutes you are talking about 20 vs 10 minutes a day. Even allowing for the interquartile ranges it really is not more than 50 minutes of saturation less than 90% at 36 weeks. The difference of course as you increase in gestation becomes less as well. When looking at the amount of time spent under 80% for the groups at the three different gestational ages there is still a difference but the amount of time at 36, 37 and 38 weeks was 229, 118 and 84 seconds respectively without caffeine (about 4, 2 and 1 minute per day respectively) vs 83, 41, and 22 seconds in the caffeine groups. I can’t help but think this is a case of statistical significance with questionable clinical significance. The authors don’t indicate that any patients were readmitted with “blue spells” who were being monitored at home which then leaves the sole question in my mind being “Do these brief periods of hypoxemia matter?” In the absence of a long-term follow-up study I would have to say I don’t know but while I have always been a fan of caffeine I am just not sure.

Should we be in a rush to stop caffeine? Well, given that the long term results of the CAP study suggest the drug is safe in the preterm population I would suggest there is no reason to be concerned about continuing caffeine a little longer. If the goal is getting patients home and discharging on caffeine is something you are comfortable with then continuing past 35 weeks is something that may have clinical impact. At the very least I remain comfortable in my own practice of not being in a rush to stop this medication and on occasion sending a patient home with it as well.

by All Things Neonatal | Aug 23, 2017 | donor milk, Neonatology, nutrition, preemie, Prematurity

Exclusive human milk (EHM) diets using either mother’s own milk or donor milk plus a human based human milk fortifier have been the subject of many papers over the last few years. Such papers have demonstrated reductions is such outcomes as NEC, length of stay, days of TPN and number of times feedings are held due to feeding intolerance to name just a few outcomes. There is little argument that a diet for a human child composed of human milk makes a great deal of sense. Although we have come to rely on bovine sources of both milk and fortifier when human milk is unavailable I am often reminded that bovine or cow’s milk is for baby cows.

Challenges with using an exclusive human milk diet.

While it makes intuitive sense to strive for an exclusive human milk diet, there are barriers to the same. Low rates of maternal breastfeeding coupled with limited or no exposure to donor breast milk programs are a clear impediment. Even if you have those first two issues minimized through excellent rates of breast milk provision, there remains the issue of whether one has access to a human based fortifier to achieve the “exclusive” human milk diet.

The “exclusive” approach is one that in the perfect world we would all strive for but in times of fiscal constraint there is no question that any and all programs will be questioned from a cost-benefit standpoint. The issue of cost has been addressed previously by Ganapathy et al in their paper Costs of Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Cost-Effectiveness of Exclusively Human Milk-Based Products in Feeding Extremely Premature Infants. The authors were able to demonstrate that choosing an exclusive human milk diet is cost effective in addition to the benefits observed clinically from such a diet. In Canada where direct costs are more difficult to visualize and a reduction in nursing staff per shift brings about the most direct savings, such an argument becomes more difficult to achieve.

Detractors from the EHM diet argue that we have been using bovine fortification from many years and the vast majority of infants regardless of gestational age have little challenge with it. Growth rates of 15-20 g/kg/d are achievable using such fortification so why would you need to treat all patients with an EHM diet?

A Rescue Approach

In our own centre we were faced with these exact questions and developed a rescue approach. The rescue was designed to identify those infants who seemed to have a clear intolerance to bovine fortifier as all of the patients we care for under 1250g receive either mother’s own or donor milk. The approach used was as follows:

A. < 27 weeks 0 days or < 1250 g

i. 2 episode of intolerance to HMF

ii. Continue for 2 weeks

This month we published our results from using this targeted rescue approach in Winnipeg, Human Based Human Milk Fortifier as Rescue Therapy in Very Low Birth Weight Infants Demonstrating Intolerance to Bovine Based Human Milk Fortifier with Dr. Sandhu being the primary author (who wrote this as a medical student with myself and others. We are thrilled to share our experience and describe the cases we have experienced in detail in the paper. Suffice to say though that we have identified value in such an approach and have now modified our current approach based on this experience to the following protocol for using human derived human milk fortifier in our centre to the current:

A. < 27 weeks 0 days or < 1250 g

i. 1 episode of intolerance to HMF

ii. Continue for 4 weeks

B. ≥ 27 week 0 days or ≥ 750g

i. 2 episodes of intolerance to HMF

ii. Continue for 4 weeks or to 32 weeks 0 days whichever comes sooner

We believe given our current contraints, this approach will reduce the risk of NEC, feeding intolerance and ultimately length of stay while being fiscally prudent in these challenging times. Given the interest at least in Canada with what we have been doing here in Winnipeg and with the publication of our results it seemed like the right time to share this with you. Whether this approach or one that is based on providing human based human milk fortifier to all infants <1250g is a matter of choice for each institution that chooses to use a product such as Prolacta. In no way is this meant to be a promotional piece but rather to provide an option for those centres that would like to use such products to offer an EHM diet but for a variety of reasons have opted not to provide it to all.

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 21, 2016 | nutrition, preemie, Prematurity

A strange title perhaps but not when you consider that both are in much need of increasing muscle mass. Muscle takes protein to build and a global market exists in the adult world to achieve this goal. For the preterm infant human milk fortifiers provide added protein and when the amounts remain suboptimal there are either powdered or liquid protein fortifiers that can be added to the strategy to achieve growth. When it comes to the preterm infant we rely on nutritional science to guide us. How much is enough? The European Society For Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition published recommendations in 2010 based on consensus and concluded:

“We therefore recommend aiming at 4.0 to 4.5 g/kg/day protein intake for infants up to 1000 g, and 3.5 to 4.0 g/kg/day for infants from 1000 to 1800 g that will meet the needs of most preterm infants. Protein intake can be reduced towards discharge if the infant’s growth pattern allows for this. The recommended range of protein intake is therefore 3.5 to 4.5 g/kg/day.”

These recommendations are from six years ago though and are based on evidence that preceded their working group so one would hope that the evidence still supports such practice. It may not be as concrete though as one would hope.

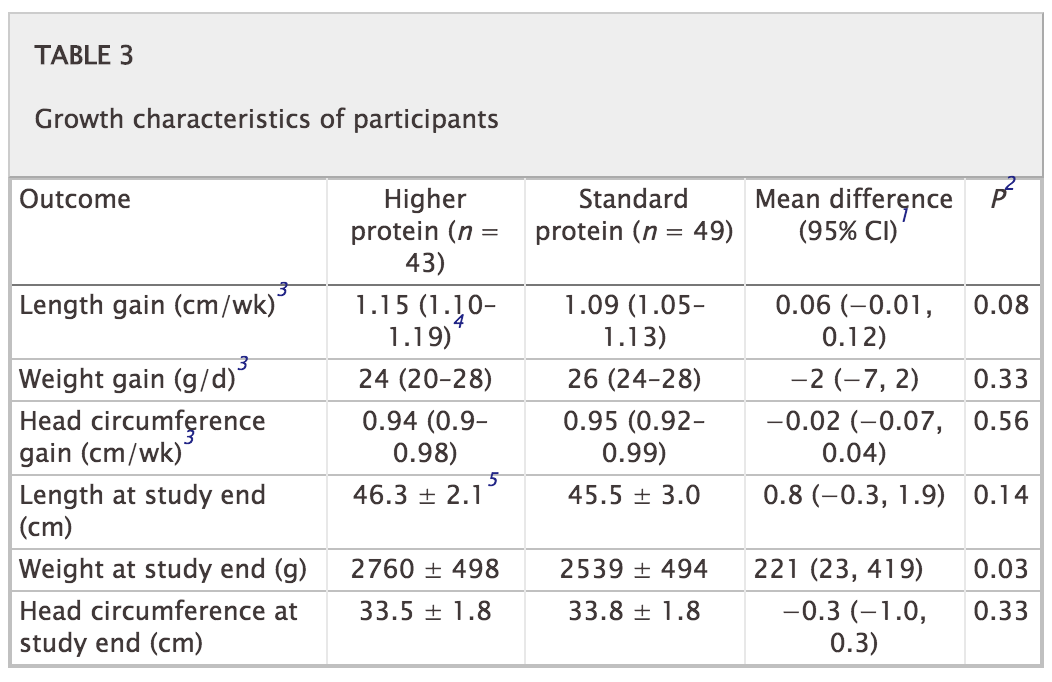

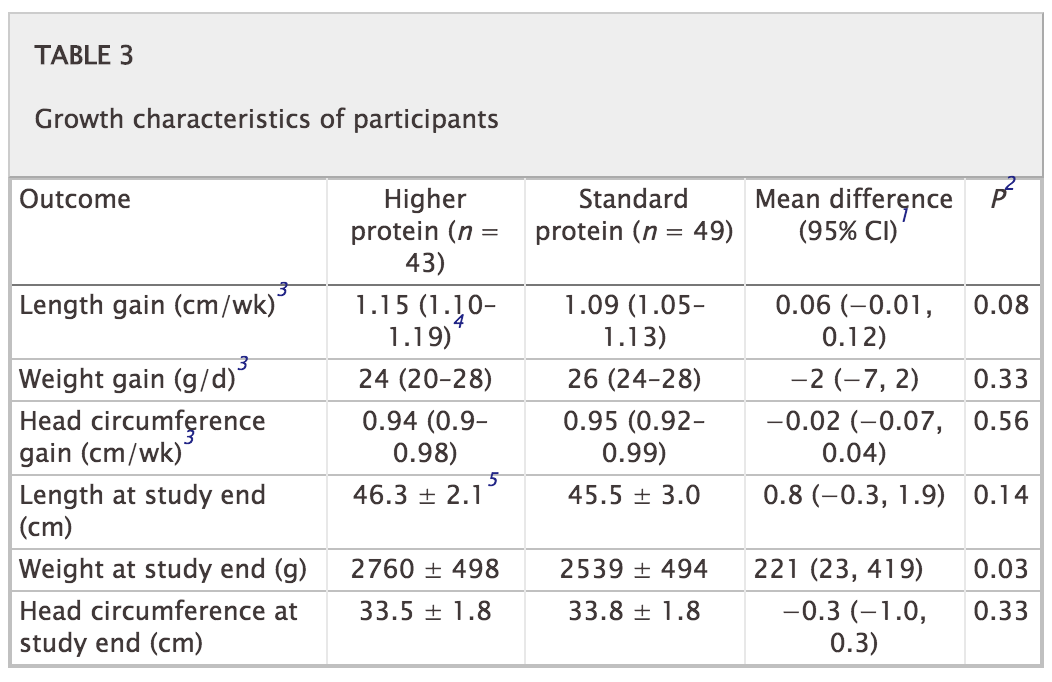

Let’s Jump To 2012

Miller et al published an RCT on the subject entitled Effect of increasing protein content of human milk fortifier on growth in preterm infants born at <31 wk gestation: a randomized controlled trial. This trial is quite relevant in that it involved 92 infants (mean GA 27-28 weeks and about 1000g on average at the start), 43 of whom received a standard amount of protein 3.6 g/kg/day vs 4.2 g/kg/d in the high protein group. This was commenced once fortification was started and carried through till discharge with energy intakes and volume of feeds being the same in both groups. The authors used a milk analyzer to ensure consistency in the total content of nutrition given the known variability in human milk nutritional content. The results didn’t show much to write home about. There were no differences in weight gain or any measurements but the weight at discharge was a little higher in the high protein group. The length of stay trended towards a higher number of days in the high protein group so that may account for some of the difference. All in all though 3.6 or 4.2 g/kg/d of protein didn’t seem to do much to enhance growth.

Now let’s jump to 2016

This past month Maas C et al published an interesting trial on protein supplementation entitled Effect of Increased Enteral Protein Intake on Growth in Human Milk-Fed Preterm Infants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. This modern day study had an interesting question to answer. How would growth compare if infants who were fed human milk were supplemented with one of three protein contents based on current recommendations. The first group of 30 infants all < 32 weeks received standard protein intake of 3.5 g/kg/d while the second group of 30 were given an average intake of 4.1 g/kg/d. The second group of 30 were divided though into an empiric group in which the protein content of maternal or donor milk was assumed to be a standard amount while the second 15 had their protein additive customized based on an analysis of the human milk being provided. Whether the higher intake group was estimated or customized resulted in no difference in protein intake on average although variability between infants in actual intake was reduced. Importantly, energy intake was no different between the high and low groups so if any difference in growth was found it would presumably be related to the added protein.

Does it make a difference?

The results of this study failed to show any benefit to head circumference, length or weight between the two groups. The authors in their discussion postulate that there is a ceiling effect when it comes to protein and I would tend to agree. There is no question that if one removes protein from the diet an infant cannot grow as they would begin to break down muscle to survive. At some point the minimum threshold is met and as one increases protein and energy intake desired growth rates ensue. What this study suggests though is that there comes a point where more protein does not equal more growth. It is possible to increase energy intakes further as well but then we run the risk of increasing adiposity in these patients.

I suppose it would be a good time to express what I am not saying! Protein is needed for the growing preterm infant so I am not jumping on the bandwagon of suggesting that we should question the use of protein fortification. I believe though that the “ceiling” for protein use lies somewhere between 3.5 – 4 g/kg/d of protein intake. We don’t really know if it is at 3.5, 3.7, 3.8 or 3.9 but it likely is sitting somewhere in those numbers. It seems reasonable to me to aim for this range but follow urea (something outside of renal failure I have personally not paid much attention to). If the urea begins rising at a higher protein intake approaching 4 g/kg/d perhaps that is the bodies way of saying enough!

Lastly this study also raises a question in my mind about the utility of milk analyzers. At least for protein content knowing precisely how much is in breastmilk may not be that important in the end. Then again that raises the whole question of the accuracy of such devices but I imagine that could be the source of a post for another day.