by All Things Neonatal | Mar 21, 2019 | steroids

I feel like this has been a story in the making for some time. Next to caffeine, the story of prophylactic hydrocortisone must be one of my more popular topics and has been covered more than once before as in A Shocking Change in Position. Postnatal steroids for ALL microprems or Early Hydrocortisone: Short term gain without long term pain. and the last post Hydrocortisone after birth may benefit the smallest preemies the most! After reporting on this topic about once a year, a recent paper may wrap it all up in a bow for the holidays and present to us the conclusion after all this work on the topic. I was extremely interested in this topic not just because I believe this therapy may have a future in the standard approach to neonatal care for VLBWs but because I have served on the CPS Fetus and Newborn committee with two of the authors of the paper. Dr. Lacaze and Dr. Watterberg have an exceptional understanding of this topic and so when they band together with other experts in the field I take notice.

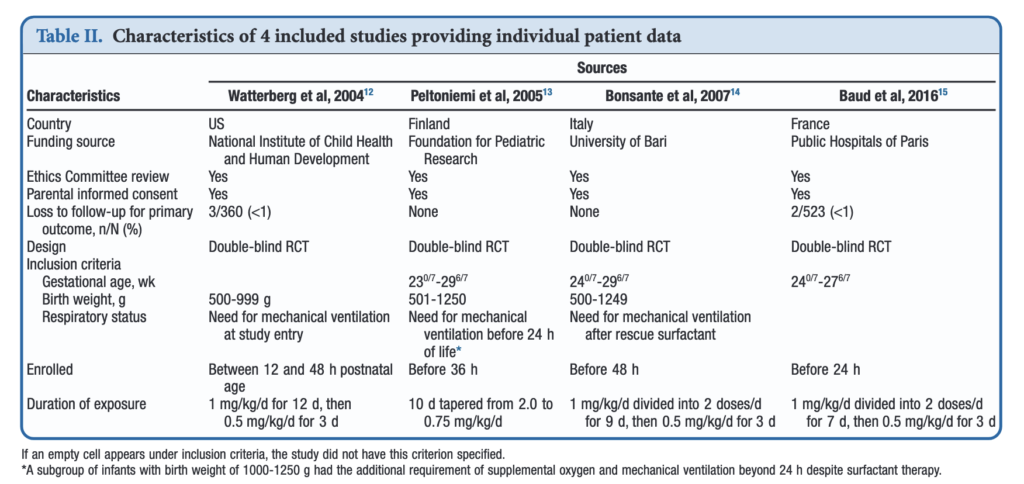

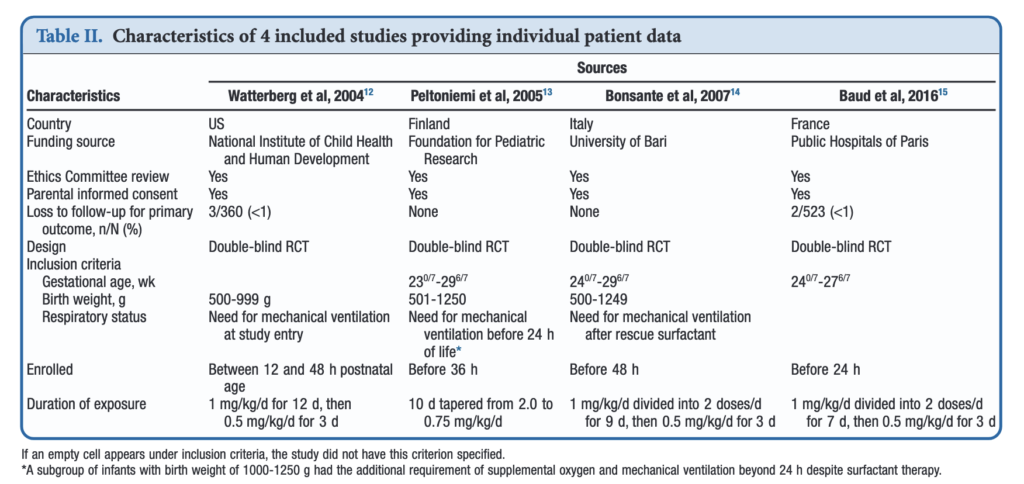

An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis

If you have read my previous posts then you know the story of why hydrocortisone given over the first 10-12 days of life might help those born before 30 weeks or < 1250g. In essence the concept is that it has been shown previously that many infants with relative adrenal insufficiency may go on to develop BPD. If you treat all such infants at risk you could theoretically reduce BPD. Typically after a few studies examining a similar topic come out, one can combine them in a meta-analysis using aggregate data (averages of effect sizes for the individual studies) and see what the larger sample shows. Another way to do it though is to go back to the original data and examine the infants at a more granular level allowing a greater identification and control of variables that might influence outcomes. This is what the authors led my Michele Shaffer did here in the paper Effect of Prophylaxis for Early Adrenal Insufficiency Using Low-Dose Hydrocortisone in Very Preterm Infants: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. There were a total of 5 studies on this topic but one study of 40 patients no longer had individual data so was excluded from analysis leaving 4 to look at. The details of the four studies are shown below. You can see that the inclusion criteria differed slightly but in general these were all infants up to 27 – 29 completed weeks and 500 – 1250g maximum who were treated with regimens as shown in the table.

What were the results?

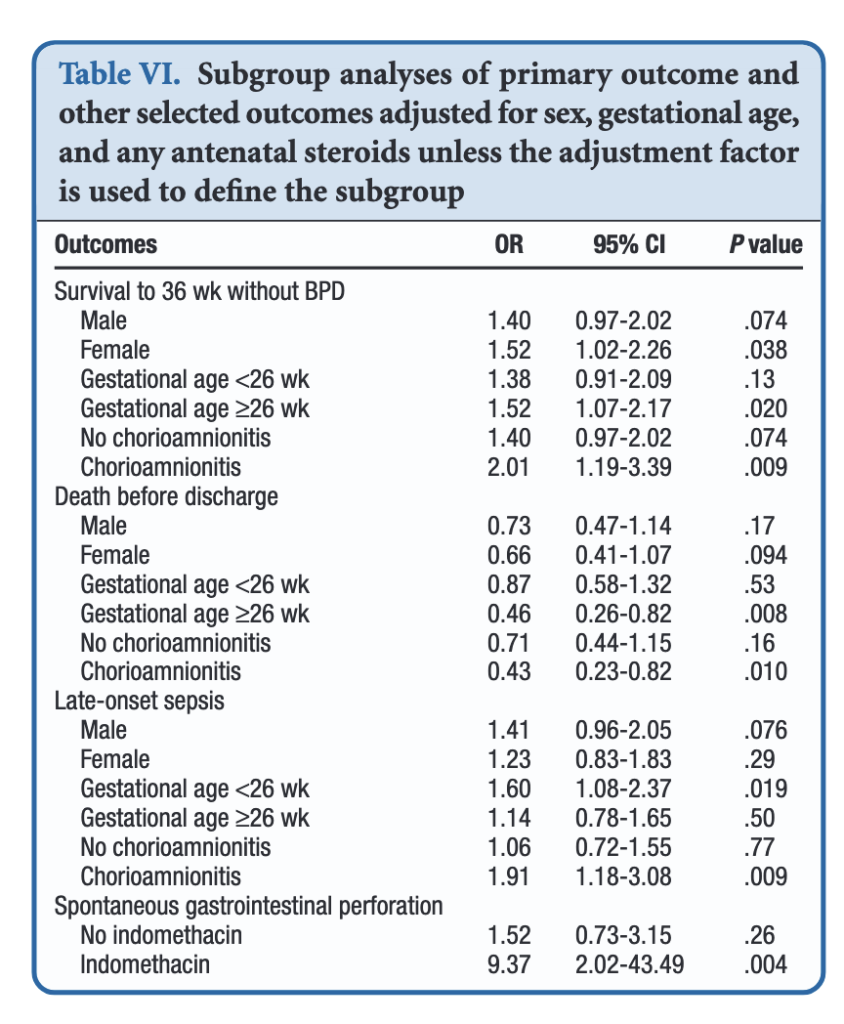

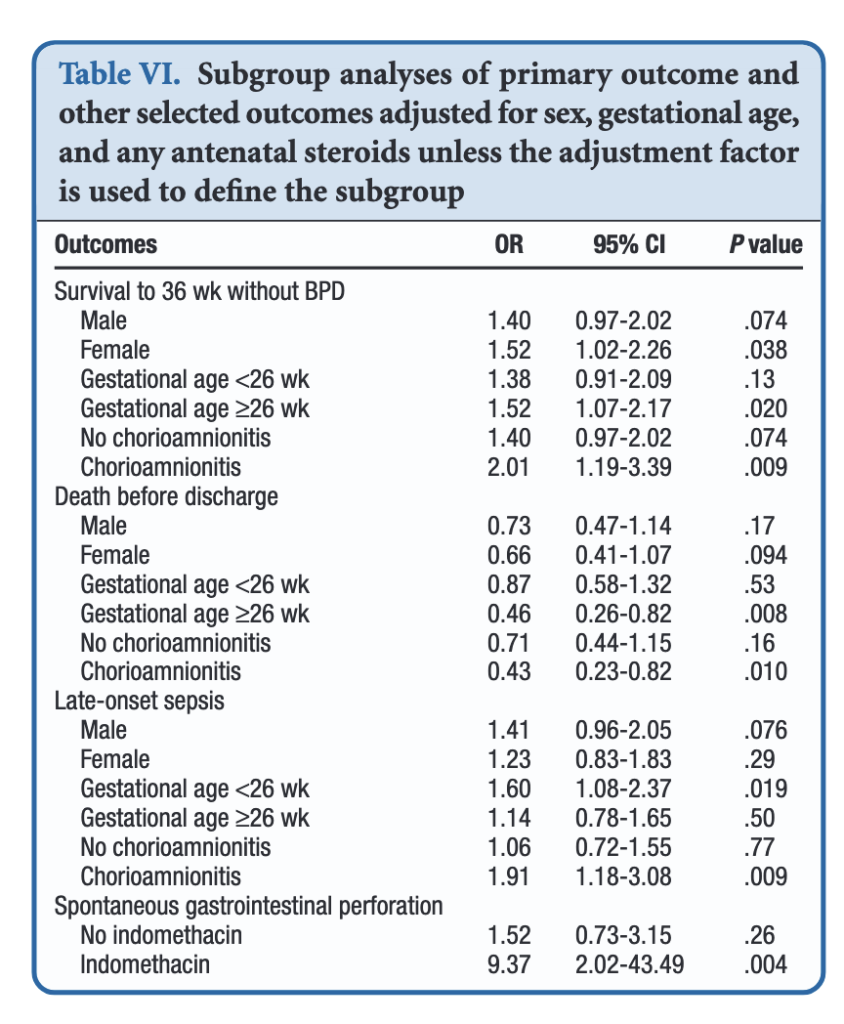

Treatment with early low-dose hydrocortisone was associated with greater odds of survival without BPD at 36 weeks PMA after adjustment for sex, gestational age, and antenatal steroid use (aOR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.11-1.90; I 2 = 0%). Also found were lower individual odds of BPD (aOR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.54-0.98; I 2 = 0%), but not with a significant decrease in death before 36 weeks PMA (aOR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.54-1.07; I 2 = 0%). Importantly although death by 36 weeks was not different, a decrease in death before discharge (aOR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51-0.97; I 2 = 0%) was found. Also noted and important was a reduction in medical treatment for PDA OR 0.72 (0.56-0.93)

All of these outcomes sound important but in a subgroup analysis other interesting findings emerged.

When dividing the patients into those less then 26 weeks and those at or greater than that gestational age, the benefits appear to be limited to those in the latter group. Levels of significance are high once you reach that GA suggesting that issues affecting those at younger gestational ages are less amenable to treatment. On the other hand one could say that the benefits seen at 26 – 29 weeks GA are relatively strong using a glass is half full approach. An important outcome worth noting is that while spontaneous intestinal perforation is noted to be a risk with prophylactic hydrocortisone, when you remove indomethacin from the equation the risk disappears. For those units using prophylactic hydrocortisone one would likely need to choose between the two but if you are like our unit where we don’t have that option this may be one strategy to consider.

In terms of risk to giving such therapy the big one noted in the paper was an increase in risk for late onset sepsis. Interestingly, this was limited though to the group under 26 weeks GA. In essence then the messaging would appear to be that under 26 weeks there may be less benefit to such treatment and therefore the increased risk of late onset sepsis without such benefits on BPD would suggest not using it in this GA group.

Where do we land then?

It would be easy to cast this aside I suppose as the group you are most worried about (22-25 weeks) doesn’t seem to really benefit but has a risk of late onset sepsis. That leaves us though with the group from 26-29 weeks. They do seem to benefit and may do so to a significant degree. They do develop BPD and to be honest we don’t have much outside of trying our best to use gentle ventilation to ameliorate their course in hospital. It is worth noting that the one group that does seem to show the greatest benefit are those exposed to chorioamnionitis. It is this group in particular that may be the best target for this intervention and I gather this has been discussed at a recent EPIQ meeting.

If one says no to trying this approach then the question that needs to be asked is whether doing nothing for this group is better than supporting them with hydrocortisone? If your centre’s rates of BPD are top notch then maybe you don’t want to add something in. If not though maybe it is time to rock the boat and try something different.

by All Things Neonatal | Mar 12, 2019 | technology

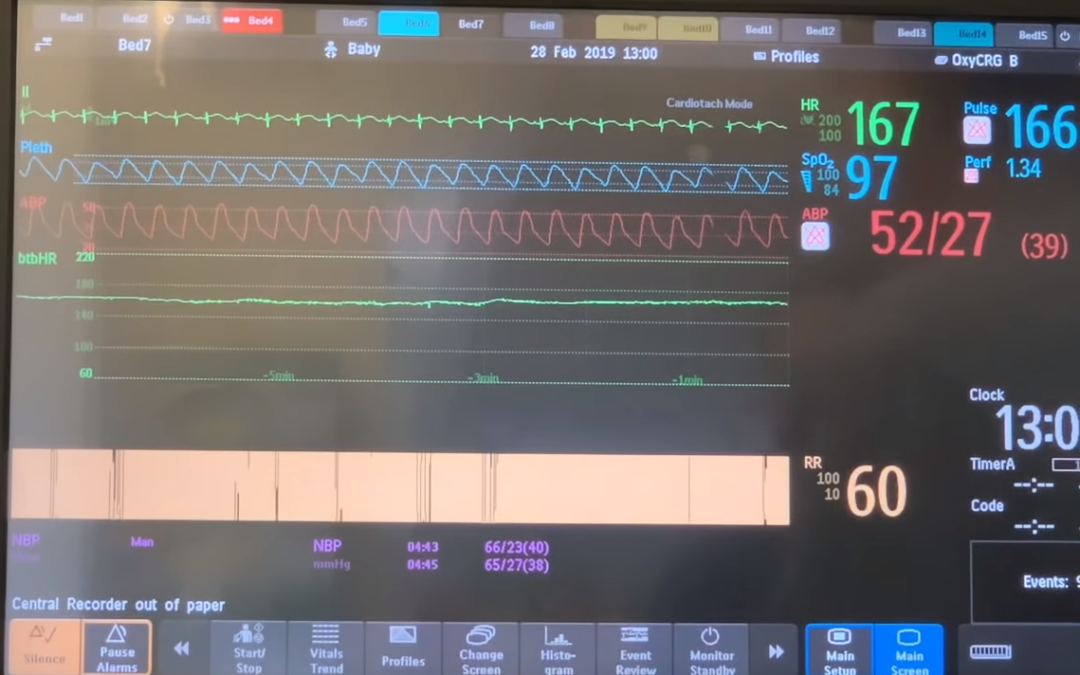

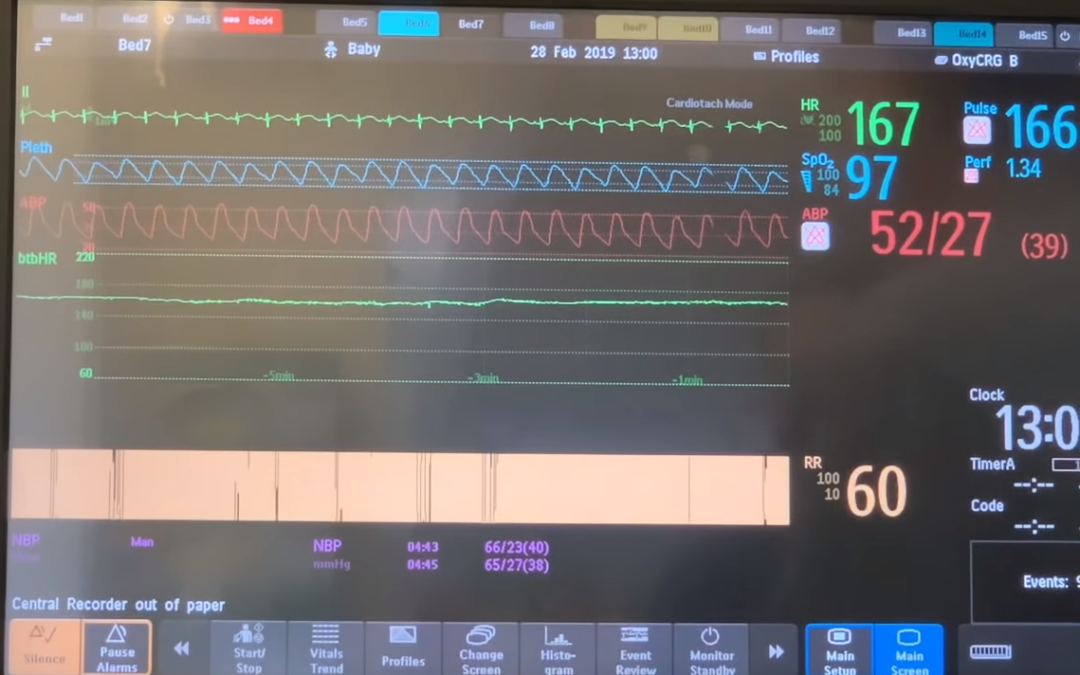

This post is very exciting to me. All of us in the field of Neonatology are used to staring at patient monitors. With each version of whatever product we are using there seems to be a new feature that is added to soothe our appetites for more data. The real estate on the screen is becoming more and more precious as various devices such as ventilators, NIRS and other machines become capable of displaying their information in a centralized place. The issue though is that there is only so much space available to display all of this information but underneath the hood so to speak is so much more!

Come Along For The Ride

One of our Neonatologists Dr. Yasser Elsayed has been very aware of these features embedded in the patient monitor. Through teaching on rounds, some of our staff have become aware of these features but delivering this content to the masses has been an issue. That is where this post and it’s linked content come into play. I have created a new Youtube playlist where all of this great content can be found. Each video is very watchable with most being 5-7 minutes long with the longest being 14:16. Each video starts with a demonstration on the patient monitor of the lesson being taught and how to access the data using the patient monitor (in this case a Phillips but I have no doubt many other monitors have the same tech – just ask your rep how to get it) followed by a brief voice-over powerpoint to deliver the essential concepts.

However you wish to digest the information is up to you but as they are short we hope that you will be able to find the content you need quickly and apply the knowledge to patient care. How can you use the information? The next time a patient is giving you cause to worry try looking into some of the deeper trends that the monitor is hiding from plain sight. Is there a trend towards becoming hypotensive for the patient that can be revealed in their blood pressure histogram? Maybe the issue lies with the way the patient is being ventilated and examining trends in the pleth waveforms may reveal where the underlying problem lies.

The Topics (click the links to go to Youtube)

Complete List of Videos

Part 1 – Using Histograms

Part 2 – How to interpret blood pressure histograms

Part 3 – Using vital signs as trends

Part 4 – Impact of ventilation on pleth waveforms

Part 5 – How to interpret arterial pressure waveforms

Part 6 – Near Infrared Spectroscopy

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 27, 2018 | hypoglycemia

In 2015 the Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) published new recommendations for defining and managing hypoglycaemia in the newborn. A colleague of mine and I discussed the changes and came to the conclusion that the changes suggested were reasonable with some “tweaks”. The PES suggested a change from 2.6 mmol/L (47 mg/dL) at 48 hours of age as a minimum goal glucose to 3.3 mmol/L (60 mg/dL) as the big change in approach. The arguments for this change was largely based on data from normal preterm and term infants achieving the higher levels by 48-72 hours and some neuroendocrine data suggesting physiologically, the body would respond with counter regulatory hormones below 3.3 mmol/L.

As it turned out, we were “early adopters” as we learned in the coming year that no other centre in Canada had paid much attention to the recommendations. The inertia to change was likely centred around a few main arguments.

1. How compelling was the data really that a target of 2.6 and above was a bad idea?

2. Fear! Would using a higher threshold result in many “well newborns” being admitted to NICU for treatment when they were really just experiencing a prolonged period of transitional hypoglycaemia.

3. If its not broken don’t fix it. In other word, people were resistant to change itself after everyone was finally accustomed to algorithms for treatment of hypoglcyemia in their own centres.

What effect did it actually have?

My colleagues along with one of our residents decided to do a before and after retrospective comparison to answer a few questions since we embraced this change. Their answers to what effect the change brought about are interesting and therefore at least a in my opinion worth sharing. If any of you are wondering what effect such change might have in your centre then read on!

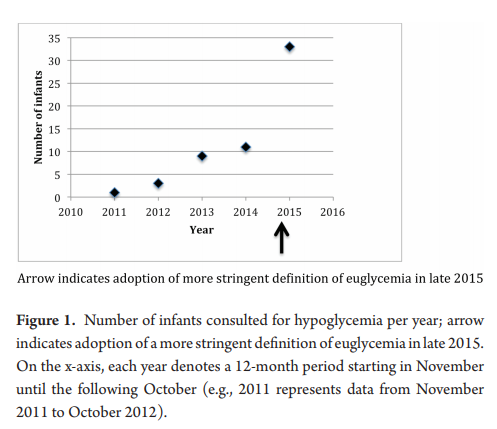

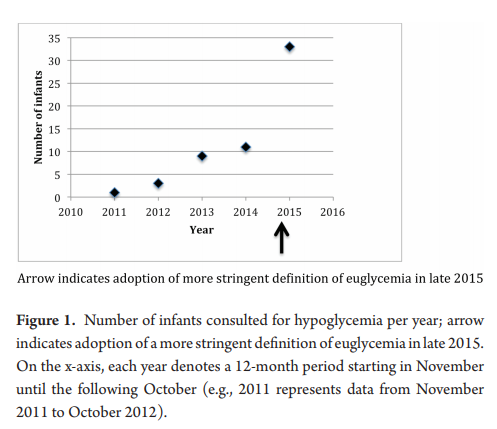

Skovrlj R, Marks S and C. Rodd published Frequency and etiology of persistent neonatal hypoglycemia using the more stringent 2015 Pediatric Endocrine Society hypoglycemia guidelines. They had a total of 58 infants in the study with a primary outcome being the number of endocrine consults before and after the change in practice.  Not surprisingly as the graph demonstrates the number went up.

Not surprisingly as the graph demonstrates the number went up.

Once the protocol was in place we went from arbitrary consults to mandatory so these results are not surprising. What is surprising though is that the median critical plasma glucose was 2.2 mmol/L, with no significant difference pre or post (2.0 mmol/L pre versus 2.6 mmol/L post, P=0.4) Ninety percent of the infants who were hypoglycemic beyond 72 hours of age were so in the first 72 hours. Of these infants, 90% were diagnosed with hyperinsulinemia. What this tells us is that those who are going to go on to have persistent hypoglycemia will demonstrate similar blood sugars whether you use the cutoff of 2.6 or 3.3 mmol/L. You will just catch more that present a little later using the higher thresholds. How would these kids do at home if discharged with true hyperinsulinemia that wasn’t treated? I can only speculate but that can’t be good for the brain…

Now comes the really interesting part!

Of the total infants in the study, thirteen infants or 40% had plasma glucose values of 2.6 to 3.2 mmol/L at the time of consultation after November 2015. Think about that for a moment. None of these infants would have been identified using the old protocol. Nine of these infants went on to require treatment with diazoxide for persistent hyperinsulinemia. All of these infants would have been missed using the old protocol. You might ask at this point “what about the admission rate?”. Curiously an internal audit of our admission rates for hypoglycemia during this period identified a decline in our admission rates. Concurrent with this change we also rolled out the use of dextrose gels so the reduction may have been due to that as one would have expected admission rates to rise otherwise. The other thing you might ask is whether in the end we did the right thing as who says that a plasma blood glucose threshold of 3.3 mmol/L is better than using the tried and true 2.6 mmol/L cutoff?

While I don’t have a definitive answer to give you to that last question, I can leave you with something provocative to chew on. In the sugar babies study the goal glucose threshold for the first 7 days of life was 2.6 mmol/L. This cohort has been followed up and I have written about these studies before in Dextrose gel for hypoglycemia. Safe in the long run? One of the curious findings in this study was in the following table.

Although the majority of the babies in the study had only mild neurosensory impairment detectable using sophisticated testing the question is why should so many have had anything at all? I have often wondered whether the goal of keeping the blood sugar above 2.6 mmol/L as opposed to a higher level of say 3.3 mmol/L may be at play. Time will tell if we begin to see centres adopt the higher thresholds and then follow these children up. I don’t know about you but a child with a blood sugar of 2.7 mmol/L at 5 or 6 days of age would raise my eyebrow. These levels that we have used for some time seem to make sense in the first few days but for discharge something higher seems sensible.

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 6, 2018 | Neonatology, Uncategorized

Look around an NICU and you will see many infants living in incubators. All will eventually graduate to a bassinet or crib but the question always is when should that happen? The decision is usually left to nursing but I find myself often asking if a baby can be taken out. My motivation is fairly simple. Parents can more easily see and interact with their baby when they are out of the incubator. Removing the sense of “don’t touch” that exists for babies in the incubators might have the psychological benefit of encouraging more breastfeeding and kangaroo care. Both good things.

Making the leap

For ELBW and VLBW infants humidity is required then of course they need this climate controlled environment. Typically once this is no longer needed units will generally try infants out of the incubator when the temperature in the “house” is reduced to 28 degrees. Still though, it is not uncommon to hear that an infant is “too small”. Where is the threshold though that defines being too small? Past research studies have looked at two points of 1600 vs 1800g for the smallest of infants. One of these studies was a Cochrane review by New K, Flenady V, Davies MW. Transfer of preterm infants for incubator to open cot at lower versus higher body weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(9). This concluded that early transition was safe for former ELBWs at the 1600g weight cut off.

What about the majority of our babies?

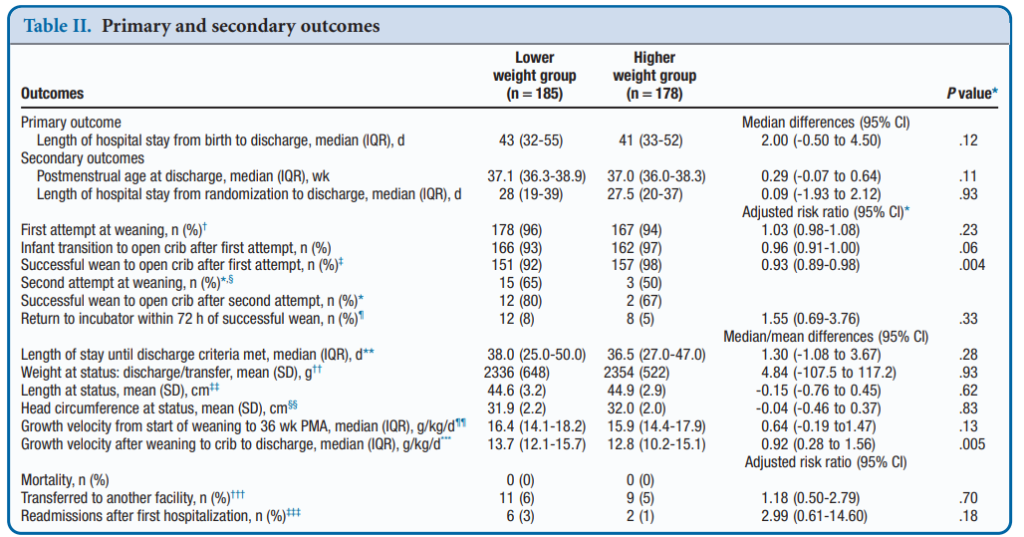

While the ELBW group takes up a considerable amount of energy and resources the later preterm infants from 29 to 33 6/7 weeks are a much larger group of babies. How safe is this transition for this group at these weights? Shankaran et al from the NICHD published an RCT on this topic recently; Weaning of Moderately Preterm Infants from the Incubator to the Crib: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The study enrolled

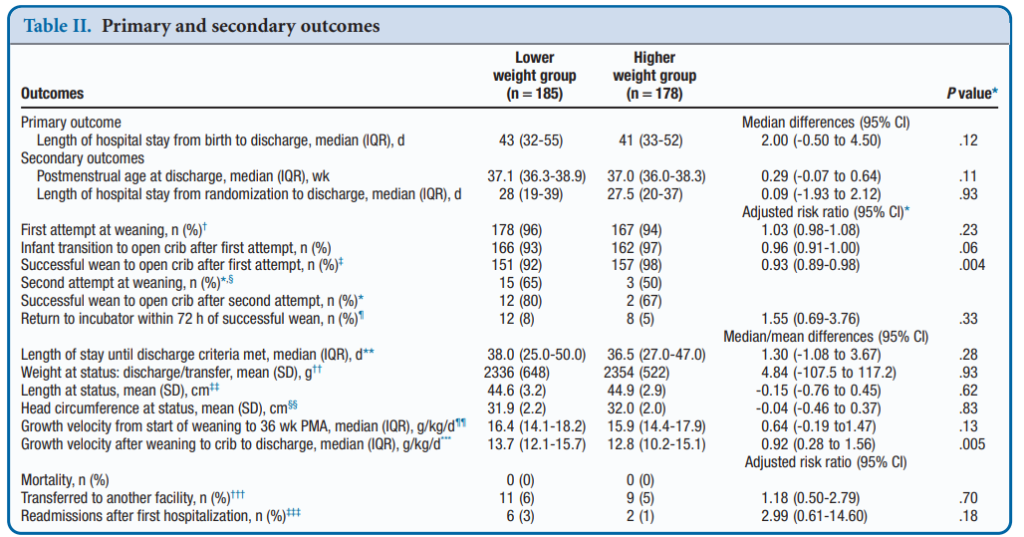

Infants in this gestational age range with a birth weight <1600g were randomly assigned to a weaning weight of 1600 or 1800 g. Within 60 to 100 g of weaning weight, the incubator temperature was decreased by 1.0°C to 1.5°C every 24 hours until 28.0°C. Weaning to the crib occurred when axillary temperatures were maintained 36.5°C to 37.4°C for 8 to 12 hours. Clothing and bedcoverings were standardized. The primary outcome was LOS from birth to discharge.

What did they find?

A total of 366 babies were enrolled (187 at 1600g and 179 at 1800g. Baseline characteristics of the two groups revealed no statistical differences. Mean LOPS was a median of 43 days in the lower and 41 days in the higher weight group (P = .12). After transition to a crib weight gain was better in the lower weight group, 13.7 g/kg/day vs 12.8 g/kg/ day (P = .005). Tracking of adverse events such as the incidence of severe hypothermia did not differ between groups. The only real significant difference was a better likelihood of weaning from the incubator in the higher group at 98% success vs 92% on the first attempt. Putting. That in perspective though, a 92% success rate by my standards is high enough to make an attempt worthwhile!

Concluding thoughts

The authors have essentially shown that whether you wean at the higher or lower weight threshold your chances of success are pretty much the same. Curiously, weight gain after weaning was improved which seems counter intuitive. I would have thought that these infants would have to work extra hard metabolically to maintain their temperature and have a lower weight gain but that was not the case. Interestingly, this finding has been shown in another study as well; New K, Flint A, Bogossian F, East C, Davies MW. Transferring preterm infants from incubators to open cots at 1600 g: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2012;97:F88-92. Metabolic rate has been shown to increase in these infants but skin fold thickness has been shown to increase as well in infants moved to a crib. How these two things go together is a little beyond me as I would have thought that as metabolic rate increases storage of tissue would slow. Not apparently the case but perhaps just another example of the bodies ability to overcome challenges when put in difficult situations. A case maybe of “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger?”

The authors do point out that the intervention was unmasked but the standardization of weaning procedure and garments used in the cribs should have overcome that. There were 36% of parents who did not consent to the study so their inclusion could have swayed the results perhaps but the sample size here was large despite that. That the final results agree with findings in ELBW infants suggests that the results are plausible.

What I think this study does though is tell us overall that weaning at a smaller weight is at least alright to try once one is at minimal settings in an incubator. Will this change your units practice? It is something that at least merits discussion.

by All Things Neonatal | Nov 15, 2018 | Breastfeeding

As a Neonatologist, there is no question that I am supportive of breast milk for preterm infants. When I first meet a family I ask the question “are you planning on breastfeeding” and know that other members of our team do the same. Before I get into the rest of this post, I realize that while breast milk may be optimal for these infants there are mother’s who can’t or won’t for a variety of reasons produce enough breast milk for their infants. Fortunately in Manitoba and many other places in the world breast milk banks have been developed to provide donor milk for supporting these families. Avoidance of formula in the early days to weeks of a ELBWs life carries benefits such as a reduction in NEC which is something we all want to see.

Mother’s own milk though is known to have additional benefits compared to donor milk which requires processing and in so doing removes some important qualities. Mother’s own milk contains more immunologic properties than donor including increased amounts of lactoferrin and contains bioactive cells. Growth on donor human milk is also reduced compared to mothers’ own milk and lastly since donor milk is obtained from mothers producing term milk there will be properties that differ from that of mothers producing fresh breast milk in the preterm period. I have no doubt there are many more detailed differences but for basic differences are these and form the basis for what is to come.

The Dose Response Effect of Mother’s Own Milk

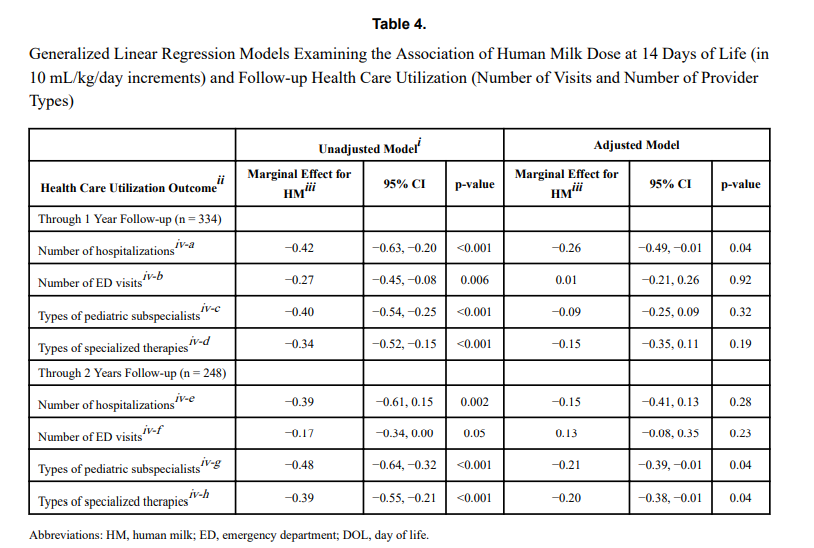

Breast milk is a powerful thing. Previous studies on the impact of mother’s own milk (MOM) have shown that with every increment of 10 mL/kg/d of average intake, the risk of such outcomes as BPD and adverse developmental outcomes are decreased. In the case of BPD the effect is considerable with a 9.5% reduction in the odds of BPD for every 10% increase in MOM dose. With respect to developmental outcome ach 10 mL/kg/day increase in MOM was associated with a 0.35 increase in cognitive index score.

One of the best names for a study has to be the LOVE MOM study which enrolled 430 VLBW infants from 2008-2012. The results of this study Impact of early human milk on sepsis and health-care costs in very low birth weight infants.indicated that with incremental increases of 10 mL/kg of MOM reductions in sepsis of 19% were achieved and in addition overall costs were reduced.

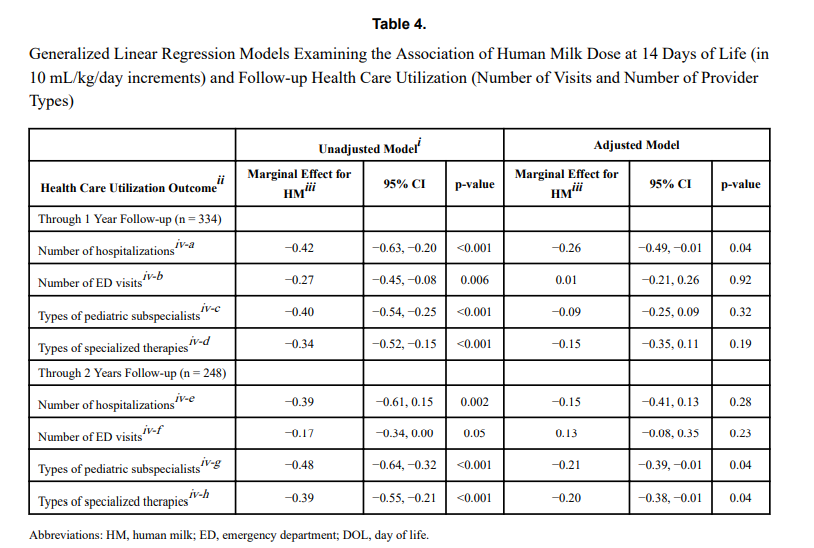

The same group just published another paper on this cohort looking at a different angle. NICU human milk dose and health care use after NICU discharge in very low birth weight infants. This study is as described and again looked at the impact of every 10 mL/kg increase in MOM at two time points; the first 14 and the first 28 days of life. Although the data for the LOVE MOM trial was collected prospectively it is important to recognize how the data for this study was procured. At the first visit after NICU discharge the caregiver was asked about hospitalizations, ED visits and specialized therapies and specialist appointments. These were all tracked at 4 and 8 months of corrected age were added to yield health care utilization in the first year, and the number of visits or provider types at 4, 8, and 20 months of corrected age provided health care utilization through 2 years.

What were the results?

“Each 10 mL/kg/day increase in HM in the first 14 days of life was associated with 0.26 fewer hospitalizations (p =

0.04) at 1 year and 0.21 fewer pediatric subspecialist types (p = 0.04) and 0.20 fewer specialized therapy types (p = 0.04) at 2 years.” The results at 28 days were not statistically significant. The authors reported both unadjusted and adjusted results controlling for many factors such as gestational age, completion of appointments and maternal education to name a few which may have influenced the results. The message therefore is that the more of MOM a VLBW is provided in the first 14 days of life, the better off they are in the first two years of life with respect to health care utilization.

That even makes some sense to me. The highest acuity typically for such infants is the first couple of weeks when they are dealing with RDS, PDA, higher oxygen requirements etc. Could the protective effects of MOM have the greatest bang for your buck during this time. By the time you reach 28 days is the effect less pronounced as you have selected out a different group of infants at that time point?

What is the weakness here though? The biggest risk I see in a study like this is recall bias. Many VLBW infants who leave the NICU have multiple issues requiring many different care providers and services. Some families might keep rigorous records of all appointments in a book while others might document some and not others. The big risk here in this study is that it is possible that some parents overstated the utilization rates and others under-reported. Not intentionally but if you have had 20 appointments in the first eight months could the number really by 18 or 22?

Another possibility is that infants receiving higher doses of MOM were healthier at the outset. Maternal stress may decrease milk production so might mothers who had healthier infants have been able to produce more milk? Are healthier infants in the first 14 days of life less likely to require more health care needs in the long term?

How do we use this information?

In spite of the caveats that I mentioned above there are multiple papers now showing the same thing. With each increment of 10 mL/kg of MOM benefits will be seen. It is not a binary effect meaning breastfed vs not. Rather much like the medications we use to treat a myriad of conditions there appears to be a dose response. It is not enough to ask the question “Are you intending to breastfeed?”. Rather it is incumbent on all of us to ask the follow-up question when a mother says yes; “How can we help you increase your production?” if that is what the family wants>

Not surprisingly as the graph demonstrates the number went up.

Not surprisingly as the graph demonstrates the number went up.