by All Things Neonatal | Feb 28, 2018 | resuscitation, technology, ventilation

The lungs of a preterm infant are so fragile that over time pressure limited time cycled ventilation has given way to volume guaranteed (VG) or at least measured breaths. It really hasn’t been that long that this has been in vogue. As a fellow I moved from one program that only used VG modes to another program where VG may as well have been a four letter word. With time and some good research it has become evident that minimizing excessive tidal volumes by controlling the volume provided with each breath is the way to go in the NICU and was the subject of a Cochrane review entitled Volume-targeted versus pressure-limited ventilation in neonates. In case you missed it, the highlights are that neonates ventilated with volume instead of pressure limits had reduced rates of:

death or BPD

pneumothoraces

hypocarbia

severe cranial ultrasound pathologies

duration of ventilation

These are all outcomes that matter greatly but the question is would starting this approach earlier make an even bigger difference?

Volume Ventilation In The Delivery Room

I was taught a long time ago that overdistending the lungs of an ELBW in the first few breaths can make the difference between a baby who extubates quickly and one who goes onto have terribly scarred lungs and a reliance on ventilation for a protracted period of time. How do we ventilate the newborn though? Some use a self inflating bag, others an anaesthesia bag and still others a t-piece resuscitator. In each case one either attempts to deliver a PIP using the sensitivity of their hand or sets a pressure as with a t-piece resuscitator and hopes that the delivered volume gets into the lungs. The question though is how much are we giving when we do that?

High or Low – Does it make a difference to rates of IVH?

One of my favourite groups in Edmonton recently published the following paper; Impact of delivered tidal volume on the occurrence of intraventricular haemorrhage in preterm infants during positive pressure ventilation in the delivery room. This prospective study used a t-piece resuscitator with a flow sensor attached that was able to calculate the volume of each breath delivered over 120 seconds to babies born at < 29 weeks who required support for that duration. In each case the pressure was set at 24 for PIP and +6 for PEEP. The question on the authors’ minds was that all other things being equal (baseline characteristics of the two groups were the same) would 41 infants given a mean volume < 6 ml/kg have less IVH compared to the larger group of 124 with a mean Vt of > 6 ml/kg. Before getting into the results, the median numbers for each group were 5.3 and 8.7 mL/kg respectively for the low and high groups. The higher group having a median quite different from the mean suggests the distribution of values was skewed to the left meaning a greater number of babies were ventilated with lower values but that some ones with higher values dragged the median up.

Results

| IVH |

< 6 mL/kg |

> 6 ml/kg |

p |

| 1 |

5% |

48% |

|

| 2 |

2% |

13% |

|

| 3 |

0 |

5% |

|

| 4 |

5% |

35% |

|

| Grade 3 or 4 |

6% |

27% |

0.01 |

| All grades |

12% |

51% |

0.008 |

Let’s be fair though and acknowledge that much can happen from the time a patient leaves the delivery room until the time of their head ultrasounds. The authors did a reasonable job though of accounting for these things by looking at such variables as NIRS cerebral oxygenation readings, blood pressures, rates of prophylactic indomethacin use all of which might be expected to influence rates of IVH and none were different. The message regardless from this study is that excessive tidal volume delivered after delivery is likely harmful. The problem now is what to do about it?

The Quandary

Unless I am mistaken, there isn’t a volume regulated bag-mask device that we can turn to for control of delivered tidal volume. Given that all the babies were treated the same with the same pressures I have to believe that the babies with stiffer lungs responded less in terms of lung expansion so in essence the worse the baby, the better they did in the long run at least from the IVH standpoint. The babies with the more compliant lungs may have suffered from being “too good”. Getting a good seal and providing good breathes with a BVM takes a lot of skill and practice. This is why the t-piece resuscitator grew in popularity so quickly. If you can turn a couple of dials and place it over the mouth and nose of a baby you can ventilate a newborn. The challenge though is that there is no feedback. How much volume are you giving when you start with the same settings for everyone? What may seem easy is actually quite complicated in terms of knowing what we are truly delivering to the patient. I would put to you that someone far smarter than I needs to develop a commercially available BVM device with real-time feedback on delivered volume rather than pressure. Being able to adjust our pressure settings whether they be manual or set on a device is needed and fast!

Perhaps someone reading this might whisper in the ear of an engineer somewhere and figure out how to do this in a device that is low enough cost for everyday use.

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 28, 2017 | preemie, Prematurity, technology, ventilation

Intubation is not an easy skill to maintain with the declining opportunities that exist as we move more and more to supporting neonates with CPAP. In the tertiary centres this is true and even more so in rural centres or non academic sites where the number of deliveries are lower and the number of infants born before 37 weeks gestational age even smaller. If you are a practitioner working in such a centre you may relate to the following scenario. A woman comes in unexpectedly at 33 weeks gestational age and is in active labour. She is assessed and found to be 8 cm and is too far along to transport. The provider calls for support but there will be an estimated two hours for a team to arrive to retrieve the infant who is about to be born. The baby is born 30 minutes later and develops significant respiratory distress. There is a t-piece resuscitator available but despite application the baby needs 40% oxygen and continues to work hard to breathe. A call is made to the transport team who asks if you can intubate and give surfactant. Your reply is that you haven’t intubated in quite some time and aren’t sure if you can do it. It is in this scenario that the following strategy might be helpful.

Surfactant Administration Through and Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)

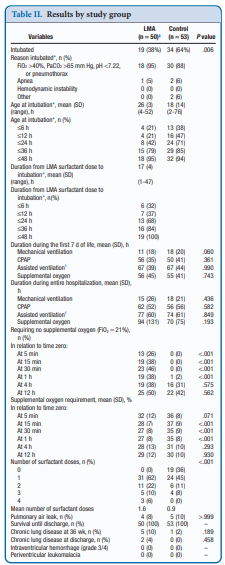

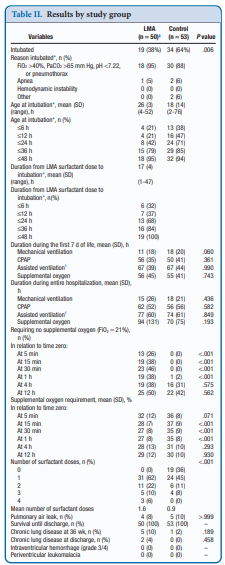

Use of an LMA has been taught for years in NRP now as a good choice to support ventilation when one can’t intubate. The device is easy enough to insert and given that it has a central lumen through which gases are exchanged it provides a means by which surfactant could be instilled through a catheter placed down the lumen of the device. Roberts KD et al published an interesting unmasked but randomized study on this topic Laryngeal Mask Airway for Surfactant Administration in Neonates: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Due to size limitations (ELBWs are too small to use this in using LMA devices) the eligible infants included those from 28 0/7 to 35 6/7 weeks and ≥1250 g. The infants needed to all be on CPAP +6 first and then fell into one of two treatment groups based on the following inclusion criteria: age ≤36 hours,

(FiO2) 0.30-0.40 for ≥30 minutes (target SpO2 88% and 92%), and chest radiograph and clinical presentation consistent with RDS.

Exclusion criteria included prior mechanical ventilation or surfactant administration, major congenital anomalies, abnormality of the airway, respiratory distress because of an etiology other than RDS, or an Apgar score <5 at 5 minutes of age.

Procedure & Primary Outcome

After the LMA was placed a y-connector was attached to the proximal end. On one side a CO2 detector was placed and then a bag valve mask in order to provide manual breaths and confirm placement over the airway. The other port was used to advance a catheter and administer curosurf in 2 mL aliquots. Prior to and then at the conclusion of the procedure the stomach contents were aspirated and the amount of surfactant determined to provide an estimate of how much surfactant was delivered to the lungs. The primary outcome was treatment failure necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation in the first 7 days of life. Treatment failure was defined upfront and required 2 of the following: (1) FiO2 >0.40 for >30

minutes (to maintain SpO2 between 88% and 92%), (2) PCO2 >65 mmHg on arterial or capillary blood gas or >70 on venous blood gas, or (3) pH <7.22 or 1 of the following: (1) recurrent or severe apnea, (2) hemodynamic instability requiring pressors, (3) repeat surfactant dose, or (4) deemed necessary by medical provider.

Did it work?

It actually did. Of the 103 patients enrolled (50 LMA and 53 control) 38% required intubation in the LMA group vs 64% in the control arm. The authors did not reach their desired enrollment based on their power calculation but that is ok given that they found a difference. What is really interesting is that they found a difference in the clinical end point despite many infants clearly not receiving a full dose of surfactant as measured by gastric aspirate. Roughly 25% of the infants were found to have not received any surfactant, 20% had >50% of the dose in the stomach and the other 50+% had < 10% of the dose in the stomach meaning that the majority was in fact deposited in the lungs. I suppose it shouldn’t come as a surprise that among the secondary outcomes the duration length of mechanical ventilation did not differ between two groups which I presume occurred due to the babies needing intubation being similar. If you needed it you needed it so to speak. Further evidence though of the effectiveness of the therapy was that the average FiO2 30 minutes after being treated was significantly lower in the group with the LMA treatment 27 vs 35%. What would have been interesting to see is if you excluded the patients who received little or no surfactant, how did the ones treated with intratracheal deposition of the dose fare? One nice thing to see though was the lack of harm as evidenced by no increased rate of pneumothorax, prolonged ventilation or higher oxygen.

Should we do this routinely?

There was a 26% reduction in intubations in te LMA group which if we take this as the absolute risk reduction means that for every 4 patients treated with an LMA surfactant approach, one patient will avoid intubation. That is pretty darn good! If we also take into account that in the real world, if we thought that little of the surfactant entered the lung we would reapply the mask and try the treatment again. Even if we didn’t do it right away we might do it hours later.

In a tertiary care centre, this approach may not be needed as a primary method. If you fail to intubate though for surfactant this might well be a safe approach to try while waiting for a more definitive airway. Importantly this won’t help you below 28 weeks or 1250g as the LMA is too small but with smaller LMAs might this be possible. Stay tuned as I suspect this is not the last we will hear of this strategy!

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 13, 2017 | BPD, Neonatal, Neonatology, preemie, ventilation

What is old is new again as the saying goes. I continue to hope that at some point in my lifetime a “cure” will be found for BPD and is likely to centre around preventing the disease from occurring. Will it be the artificial placenta that will allow this feat to be accomplished or something else? Until that day we unfortunately are stuck with having to treat the condition once it is developing and hope that we can minimize the damage. When one thinks of treating BPD we typically think of postnatal steroids. Although the risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcome is reduced with more modern approaches to use, such as with the DART protocol,most practitioners would prefer to avoid using them at all if possible. We know from previous research that a significant contributor to the development of BPD is inflammation. As science advanced, the specific culprits for this inflammatory cascade were identified and leukotrienes in particular were identified in tracheal lavage fluid from infants with severe lung disease. The question then arises as to whether or not one could ameliorate the risk of severe lung disease by halting at least a component of the inflammatory cascade leading to lung damage.

Leukotriene Antagonists

In our unit, we have tried using the drug monteleukast, an inhibitor of leukotrienes in several patients. With a small sample it is difficult to determine exactly whether this has had the desired effect but in general has been utilized when “all hope is lost”. The patient has severe disease already and is stuck on high frequency ventilation and may have already had a trial of postnatal steroids. It really is surprising that with the identification of leukotriene involvement over twenty years ago it took a team in 2014 to publish the only clinical paper on this topic. A German team published Leukotriene receptor blockade as a life-saving treatment in severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia.in 2014 and to date as far as I can see remains the only paper using this strategy. Given that we are all looking for ways to reduce BPD and this is the only such paper out there I thought you might want to see what they found. Would this be worth trying in your own unit? Well, read on and see what you think!

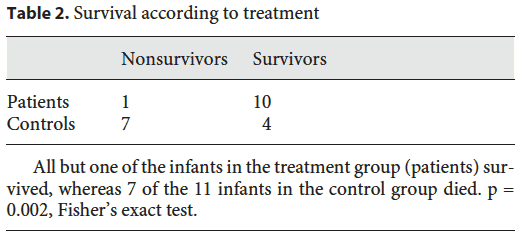

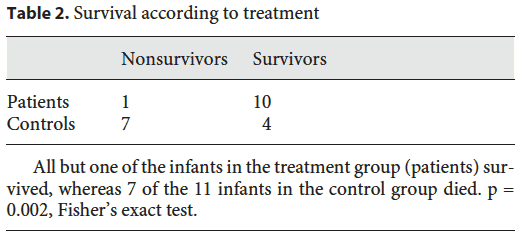

Who was included?

This study had an unusual design that will no doubt make statistical purists cringe but here is what they did. The target population for the intervention were patients with “life threatening BPD”. That is, in the opinion of the attending Neonatologist the patient had a greater than 50% likelihood of dying and also had to meet the following criteria; born at < 32 weeks GA, <1500g and had to be ventilated at 28 days. The authors sought a blinded RCT design but the Research Ethics Board refused due to the risk of the drug being low and the patients having such a high likelihood of death. The argument in essence was if the patients were likely to die and this drug might benefit them it was unethical to deny them the drug. The authors attempted to enroll all eligible patients but wound up with 11 treated and 11 controls. The controls were patients either with a contraindication to the drug or were parents who consented to be included in the study as controls but didn’t want the drug. Therapy was started for all between 28 – 45 days of age and continued for a wide range of durations (111+/-53 days in the study group). Lastly, the authors derived a score of illness severity that was used empirically:

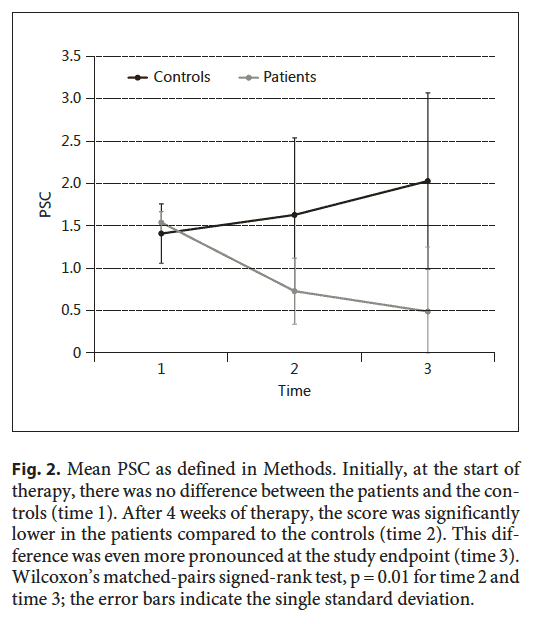

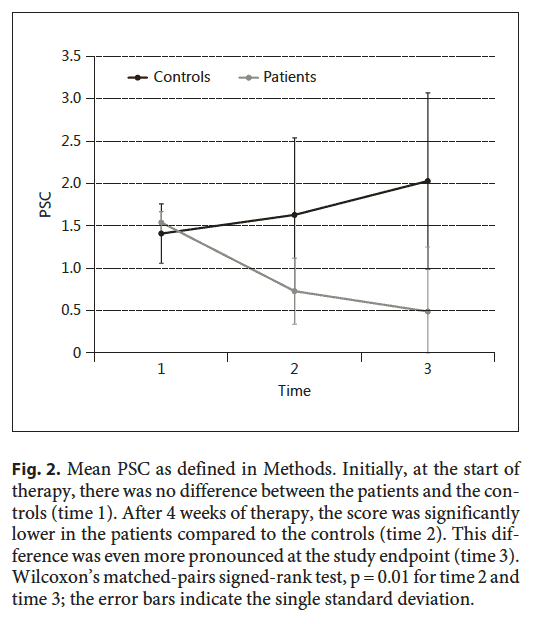

PSC = FiO2 X support + medications

– support was equal to 2.5 for a ventilator. 1.5 for CPAP and 1 for nasal cannulae or an oxygen hood

– medications were equal to 0.2 for steroids, 0.1 for diruetics or inhaled steroids, 0.05 for methylxanthines or intermittent diruetics.

Did it make a difference?

The study was very small and each patient who received the medication was matched with one that did not receive treatment. Matching was based on GA, BW and the PSC with matching done less than 48 hours after enrollment in an attempt to match the severity of illness most importantly.

First off survival in the groups were notably different. A marked improvement in outcome was noted in the two groups. Of the deaths in the control group, the causes were all pulmonary and cardiac failure, although three patients died with a diagnosis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome. That is quite interesting given that monteleukast is an anti-inflammatory medication and none of the patients in the treatment arm experienced this diagnosis.

The second point of interest is the trend in the illness severity score over time. The time points in the figure are time 1 (start of study), time 2 (4 weeks of treatment), time 3 (end of treatment). These patients improved much more over time than the ones who did not receive treatment.

The time points in the figure are time 1 (start of study), time 2 (4 weeks of treatment), time 3 (end of treatment). These patients improved much more over time than the ones who did not receive treatment.

The Grain of Salt

As exciting as the results are, we need to acknowledge a couple things. The study is small and with that the risk of the results appearing to be real but in actual fact there being no effect is not minimal. As the authors knew who was receiving monteleukast it is possible that they treated the kids differently in the unit. If you believed that the medication would work or moreover wanted it to work, did you pay more attention on rounds and during a 24 hour period to those infants? Did the babies get more blood gases and tighter control of ventilation with less damage to the lungs over time? There are many reasons why these patients could have been different including earlier attempts to extubate. The fact is though the PSC scores do show that the babies indeed improved more over time so I wouldn’t write it off entirely that they did in fact benefit. The diagnosis of SIRS is a tough one to make in a newborn and I worry a little that knowing the babies didn’t receive an anti-inflammatory drug they were “given” that diagnosis.

Would I use it in spite of these faults? Yes. We have used it in such cases but I can’t say for sure that it has worked. If it does, the effect is not immediate and we are left once we start it not knowing how long to treat. As the authors here say though, the therapeutic risk is low with a possibly large benefit. I doubt it is harmful so the question we are left asking is whether it is right for you to try in your unit? As always perhaps a larger study will be done to look at this again with a blinded RCT structure as the believers won’t show up I suspect without one!

by All Things Neonatal | Oct 25, 2017 | Neonatal, preemie, Prematurity, ventilation

A patient has been extubated to CPAP and is failing with increasing oxygen requirements or increasing apnea and bradycardia. In most cases an infant would be reintubated but is there another way? While CPAP has been around for some time to support our infants after extubation, a new method using high frequency nasal ventilation has arrived and just doesn’t want to go away. Depending on your viewpoint, maybe it should or maybe it is worth a closer look. I have written about the modality before in High Frequency Nasal Ventilation: What Are We Waiting For? While it remains a promising technology questions still remain as to whether it actually delivers as promised.

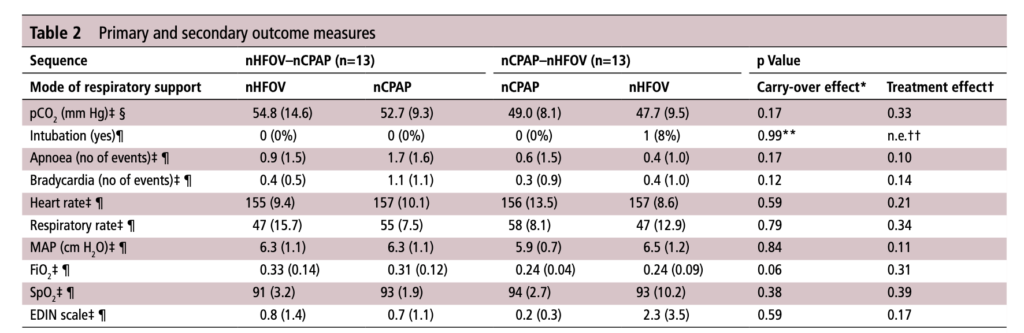

Better CO2 elimination?

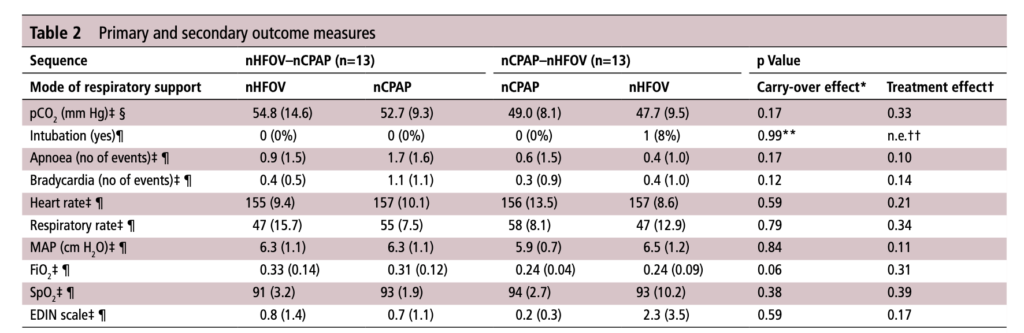

For those who have used a high frequency oscillator, you would know that it does a marvelous job of removing CO2 from the lungs. If it does so well when using an endotracheal tube, why wouldn’t it do just as good a job when used in a non-invasive way? That is the hypothesis that a group of German Neonatologists put forth in their paper this month entitled Non-invasive high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in preterm infants: a randomised controlled crossover trial. In this relatively small study of 26 preterm infants who were all less than 32 weeks at delivery, babies following extubation or less invasive surfactant application were randomized to either receive nHFOV then CPAP for four hours each or the reverse order for the same duration. The primary outcome here was reduction in pCO2 with the goal of seeking a difference of 5% or more in favour of nHFOV. Based on their power calculation they thought they would need 24 infants total and therefore exceeded that number in their enrollment.

The babies in both arms were a bit different which may have confounded the results. The group randomized to CPAP first were larger (mean BW 1083 vs 814g), and there was a much greater proportion of males in the CPAP group. As well, the group randomized first to CPAP had higher baseline O2 saturation of 95% compared to 92% in the nHFOV group. Lastly and perhaps most importantly, there was a much higher rate of capillary blood sampling instead of arterial in the CPAP first group (38% vs 15%). In all cases the numbers are small but when looking for such a small difference in pCO2 and the above mentioned factors tipping the scales one way or the other in terms of illness severity and accuracy of measurement it does give one reason to pause when looking at the results.

The Results

No difference was found in the mean pCO2 from the two groups. As expected, pCO2 obtained from capillary blood gases nearly met significance for being higher than arterial samples (50 vs 47; p=0.052). A similar rate of babies had to drop out of the study (3 on the nCPAP first and 2 on the nHFOV side).

In the end should we really be surprised by the results? I do believe that in the right baby who is about to fail nCPAP a trial of nHFOV may indeed work. By what means I really don’t understand. Is it the fact that the mean airway pressure is generally set higher than on nCPAP in some studies? Could it be the oscillatory vibration being a kind of noxious stimulus that prevents apneic events through irritation of the infant?

While traditional invasive HFOV does a marvelous job of clearing out CO2 I have to wonder how the presence of secretions and a nasopharynx that the oscillatory wave has to avoid (almost like a magic wave that takes a 90 degree turn and then moves down the airway) allows much of any of the wave to reach the distal alveoli. It would be similar to what we know of inhaled steroids being deposited 90 or so percent in the oral cavity and pharynx. There is just a lot of “stuff” in the way from the nostril to the alveolus.

This leads me to my conclusion that if it is pCO2 you are trying to lower, I wouldn’t expect any miracles with nHFOV. Is it totally useless? I don’t think so but for now as a respiratory modality I think for the time being it will continue to be “looking for a place to happen”

by All Things Neonatal | Oct 5, 2017 | Innovation, Neonatology, ventilation

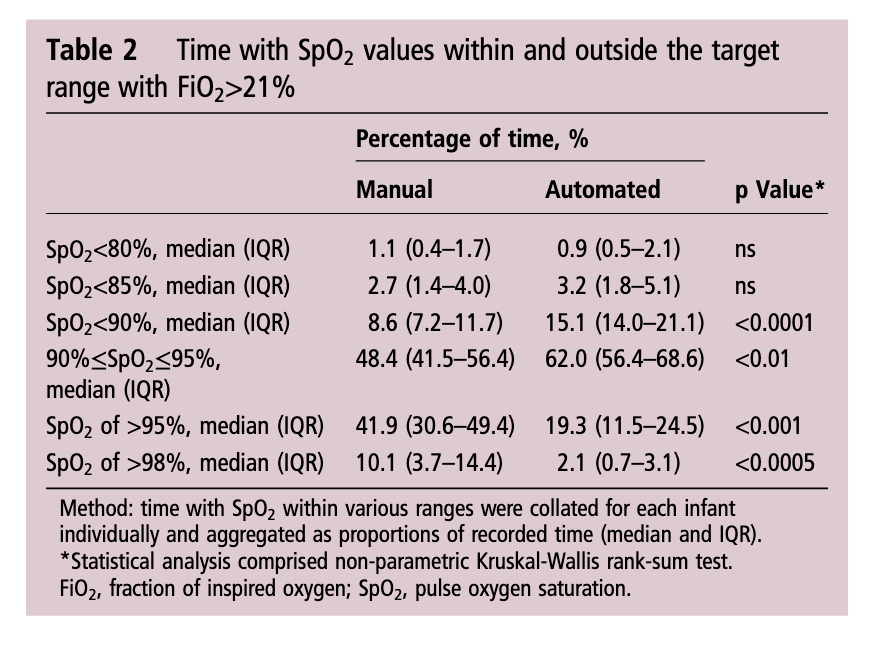

It has been over two years since I have written on this subject and it continues to be something that I get excited about whenever a publication comes my way on the topic. The last time I looked at this topic it was after the publication of a randomized trial comparing in which one arm was provided automated FiO2 adjustments while on ventilatory support and the other by manual change. Automated adjustments of FiO2. Ready for prime time? In this post I concluded that the technology was promising but like many new strategies needed to be proven in the real world. The study that the post was based on examined a 24 hour period and while the results were indeed impressive it left one wondering whether longer periods of use would demonstrate the same results. Moreover, one also has to be wary of the Hawthorne Effect whereby the results during a study may be improved simply by being part of a study.

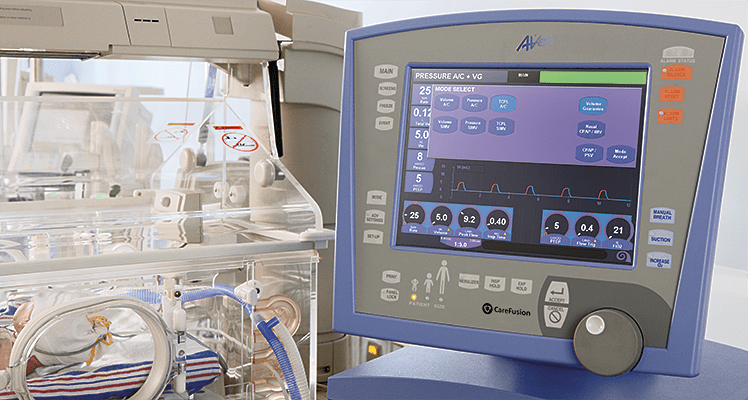

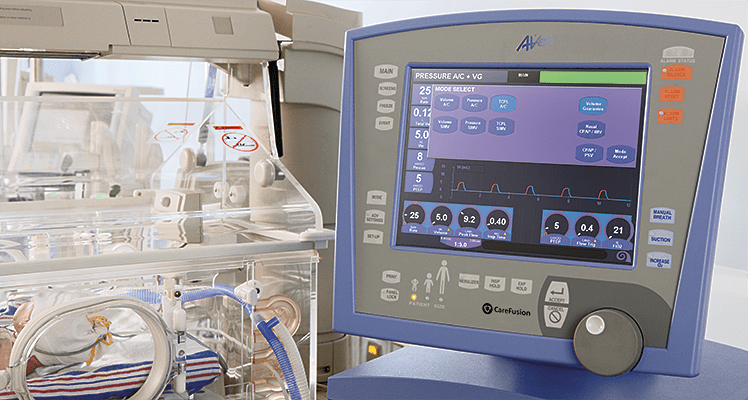

The Real World Demonstration

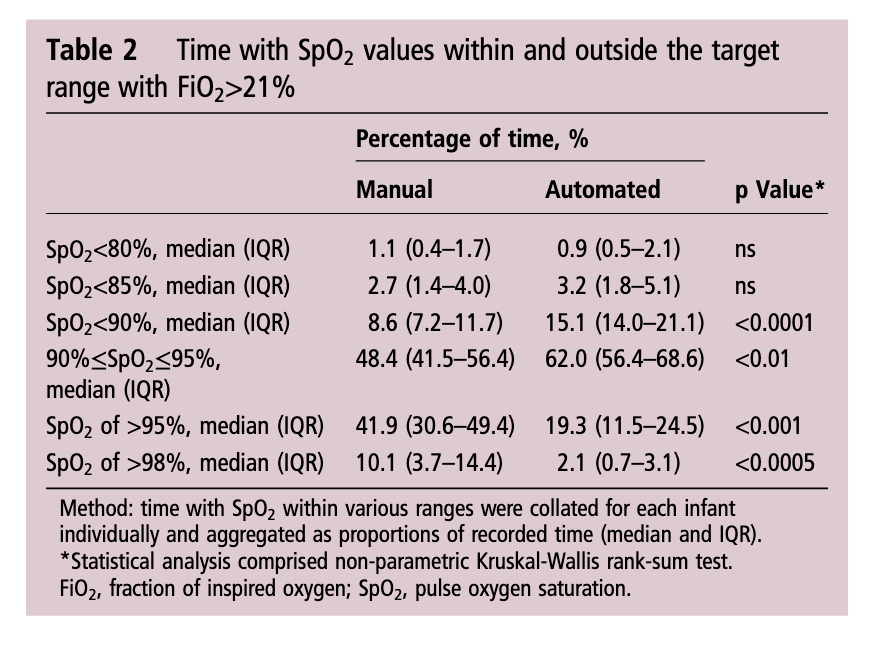

So the same group decided to look at this again but in this case did a before and after comparison. The study looked at a group of preterm infants under 30 weeks gestational age born from May – August 2015 and compared them to August to January 2016. The change in practice with the implementation of the CLiO2 system with the Avea ventilator occurred in August which allowed two groups to be looked at over a relatively short period of time with staff that would have seen little change before and after. The study in question is by Van Zanten HA The effect of implementing an automated oxygen control on oxygen saturation in preterm infants. For the study the target range of FiO2 for both time periods was 90 – 95% and the primary outcome was the percentage of time spent in this range. Secondary outcomes included time with FiO2 at > 95% (Hyperoxemia) and < 90, <85 and < 80% (hypoxemia). Data were collected when infants received respiratory support by the AVEA and onlyincluded for analysis when supplemental oxygen was given, until the infants reached a GA of 32 weeks

As you might expect since a computer was controlling the FiO2 using a feedback loop from the saturation monitor it would be a little more accurate and immediate in manipulating FiO2 than a bedside nurse who has many other tasks to manage during the care of an infant. As such the median saturation was right in the middle of the range at 93% when automated and 94% when manual control was used. Not much difference there but as was seen in the shorter 24 hour study, the distribution around the median was tighter with automation. Specifically with respect to ranges, hyperoxemia and hypoxemia the following was noted (first number is manual and second comparison automated in each case).

Time spent in target range: 48.4 (41.5–56.4)% vs 61.9 (48.5–72.3)%; p<0.01

Hyperoxemia >95%: 41.9 (30.6–49.4)% vs 19.3 (11.5–24.5)%; p<0.001

< 90%: 8.6 (7.2–11.7)% vs 15.1 (14.0–21.1)%;p<0.0001

< 85%: 2.7 (1.4–4.0)% vs 3.2 (1.8–5.1)%; ns

Hypoxemia < 80%: 1.1 (0.4–1.7)% vs 0.9 (0.5–2.1)%; ns

What does it all mean?

I find it quite interesting that while hyperoxemia is reduced, the incidence of saturations under 90% is increased with automation. I suspect the answer to this lies in the algorithmic control of the FiO2. With manual control the person at the bedside may turn up a patient (and leave them there a little while) who in particular has quite labile saturations which might explain the tendency towards higher oxygen saturations. This would have the effect of shifting the curve upwards and likely explains in part why the oxygen saturation median is slightly higher with manual control. With the algorithm in the CLiO2 there is likely a tendency to respond more gradually to changes in oxygen saturation so as not to overshoot and hyperoxygenate the patient. For a patient with labile oxygen saturations this would have a similar effect on the bottom end of the range such that patients might be expected to drift a little lower then the target of 90% as the automation corrects for the downward trend. This is supported by the fact that when you look at what is causing the increase in percentage of time below 90% it really is the category of 85-89%.

Is this safe? There will no doubt be people reading this that see the last line and immediately have flashbacks to the SUPPORT trial which created a great deal of stress in the scientific community when the patients in the 85-89% arm of the trial experienced higher than expected mortality. It remains unclear what the cause of this increased mortality was and in truth in our own unit we accept 88 – 92% as an acceptable range. I have no doubt there are units that in an attempt to lessen the rate of ROP may allow saturations to drop as low as 85% so I continue to think this strategy of using automation is a viable one.

For now the issue is one of a ventilator that is capable of doing this. If not for the ventilated patient at least for patients on CPAP. In our centre we don’t use the Avea model so that system is out. With the system we use for ventilation there is also no option. We are anxiously awaiting the availability of an automated system for our CPAP device. I hope to be able to share our own experience positively when that comes to the market. From my standpoint there is enough to do at the bedside. Having a reliable system to control the FiO2 and minimize oxidative stress is something that may make a real difference for the babies we care for and is something I am eager to see.

by All Things Neonatal | Sep 13, 2017 | Neonatal, Neonatology, newborn, preemie, Prematurity, resuscitation, ventilation

We can always learn and we can always do better. At least that is something that I believe in. In our approach to resuscitating newborns one simple rule is clear. Fluid must be replaced by air after birth and the way to oxygenate and remove CO2 is to establish a functional residual capacity. The functional residual capacity is the volume of air left in the lung after a tidal volume of air is expelled in a spontaneously breathing infant and is shown in the figure. Traditionally, to establish this volume in a newborn who is apneic, you begin PPV or in the spontaneously breathing baby with respiratory distress provide CPAP to help inflate the lungs and establish FRC.

Is there another way?

Something that has been discussed now for some time and was commented on in the most recent version of NRP was the concept of using sustained inflation (SI) to achieve FRC. I have written about this topic previously and came to a conclusion that it wasn’t quite ready for prime time yet in the piece Is It Time To Use Sustained Lung Inflation In NRP?

The conclusion as well in the NRP textbook was the following:

“There are insufficient data regarding short and long-term safety and the most appropriate duration and pressure of inflation to support routine application of sustained inflation of greater than 5 seconds’ duration to the transitioning newborn (Class IIb, LOE B-R). Further studies using carefully designed protocols are needed”

So what now could be causing me to revisit this concept? I will be frank and admit that whenever I see research out of my old unit in Edmonton I feel compelled to read it and this time was no different. The Edmonton group continues to do wonderful work in the area of resuscitation and expand the body of literature in such areas as sustained inflation.

Can you predict how much of a sustained inflation is needed?

This is the crux of a recent study using end tidal CO2 measurement to determine whether the lung has indeed established an FRC or not. Dr. Schmolzer’s group in their paper (Using exhaled CO2 to guide initial respiratory support at birth: a randomised controlled trial) used end tidal CO2 levels above 20 mmHg to indicate that FRC had been established. If you have less CO2 being released the concept would be that the lung is actually not open. There are some important numbers in this study that need to be acknowledged. The first is the population that they looked at which were infants under 32 6/7 weeks and the second is the incidence of BPD (need for O2 or respiratory support at 36 weeks) which in their unit was 49%. This is a BIG number as in comparison for infants under 1500g our own local incidence is about 11%. If you were to add larger infants closer to 33 weeks our number would be lower due to dilution. With such a large number though in Edmonton it allowed them to shoot for a 40% reduction in BPD (50% down to 30%). To accomplish this they needed 93 infants in each group to show a difference this big.

So what did they do?

For this study they divided the groups in two when the infant wouldn’t breathe in the delivery room. The SI group received a PIP of 24 using a T-piece resuscitator for an initial 20 seconds. If the pCO2 as measured by the ETCO2 remained less than 20 they received an additional 10 seconds of SI. In the PPV group after 30 seconds of PPV the infants received an increase of PIP if pCO2 remained below 20 or a decrease in PIP if above 20. In both arms after this phase of the study NRP was then followed as per usual guidelines.

The results though just didn’t come through for the primary outcome although ventilation did show a difference.

| Outcome |

SI |

PPV |

p |

| BPD |

23% |

33% |

0.09 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (hrs) |

63 |

204 |

0.045 |

The reduction in hours of ventilation was impressive although no difference in BPD was seen. The problem though with all of this is what happened after recruitment into the study. Although they started with many more patients than they needed, by the end they had only 76 in the SI group and 86 in the PPV group. Why is this a problem? If you have less patients than you needed based on the power calculation then you actually didn’t have enough patients enrolled to show a difference. The additional compounding fact here is that of the Hawthorne Effect. Simply put, patients who are in a study tend to do better by being in a study. The observed rate of BPD was 33% during the study. If the observed rate is lower than expected when the power calculation was done it means that the number needed to show a difference was even larger than the amount they originally thought was needed. In the end they just didn’t have the numbers to show a difference so there isn’t much to conclude.

What I do like though

I have a feeling or a hunch that with a larger sample size there could be something here. Using end tidal pCO2 to determine if the lung is open is in and of itself I believe a strategy to consider whether giving PPV or one day SI. We already use colorimetric devices to determine ETT placement but using a quantitative measure to ascertain the extent of open lung seems promising to me. I for one look forward to the continued work of the Neonatal Resuscitation–Stabilization–Triage team (RST team) and congratulate them on the great work that they continue doing.

The time points in the figure are time 1 (start of study), time 2 (4 weeks of treatment), time 3 (end of treatment). These patients improved much more over time than the ones who did not receive treatment.

The time points in the figure are time 1 (start of study), time 2 (4 weeks of treatment), time 3 (end of treatment). These patients improved much more over time than the ones who did not receive treatment.