by All Things Neonatal | Oct 25, 2017 | Neonatal, preemie, Prematurity, ventilation

A patient has been extubated to CPAP and is failing with increasing oxygen requirements or increasing apnea and bradycardia. In most cases an infant would be reintubated but is there another way? While CPAP has been around for some time to support our infants after extubation, a new method using high frequency nasal ventilation has arrived and just doesn’t want to go away. Depending on your viewpoint, maybe it should or maybe it is worth a closer look. I have written about the modality before in High Frequency Nasal Ventilation: What Are We Waiting For? While it remains a promising technology questions still remain as to whether it actually delivers as promised.

Better CO2 elimination?

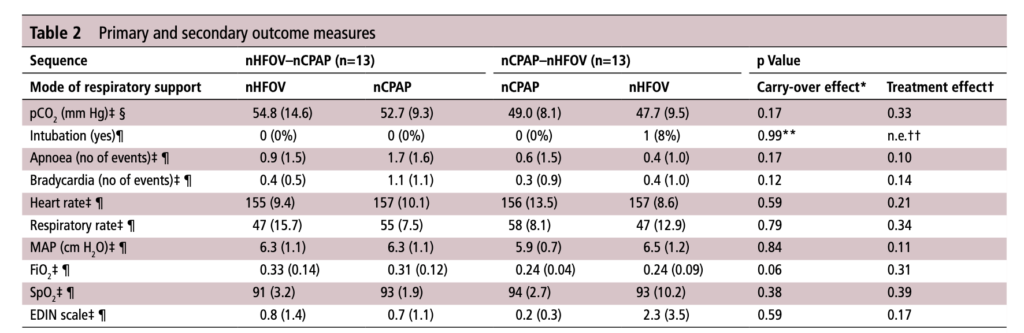

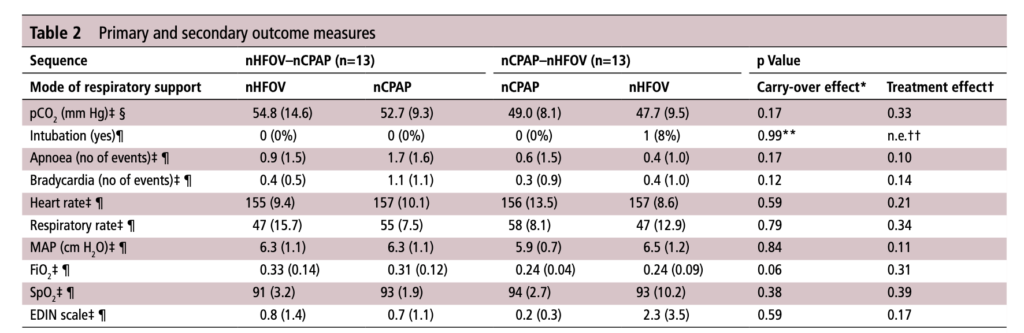

For those who have used a high frequency oscillator, you would know that it does a marvelous job of removing CO2 from the lungs. If it does so well when using an endotracheal tube, why wouldn’t it do just as good a job when used in a non-invasive way? That is the hypothesis that a group of German Neonatologists put forth in their paper this month entitled Non-invasive high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in preterm infants: a randomised controlled crossover trial. In this relatively small study of 26 preterm infants who were all less than 32 weeks at delivery, babies following extubation or less invasive surfactant application were randomized to either receive nHFOV then CPAP for four hours each or the reverse order for the same duration. The primary outcome here was reduction in pCO2 with the goal of seeking a difference of 5% or more in favour of nHFOV. Based on their power calculation they thought they would need 24 infants total and therefore exceeded that number in their enrollment.

The babies in both arms were a bit different which may have confounded the results. The group randomized to CPAP first were larger (mean BW 1083 vs 814g), and there was a much greater proportion of males in the CPAP group. As well, the group randomized first to CPAP had higher baseline O2 saturation of 95% compared to 92% in the nHFOV group. Lastly and perhaps most importantly, there was a much higher rate of capillary blood sampling instead of arterial in the CPAP first group (38% vs 15%). In all cases the numbers are small but when looking for such a small difference in pCO2 and the above mentioned factors tipping the scales one way or the other in terms of illness severity and accuracy of measurement it does give one reason to pause when looking at the results.

The Results

No difference was found in the mean pCO2 from the two groups. As expected, pCO2 obtained from capillary blood gases nearly met significance for being higher than arterial samples (50 vs 47; p=0.052). A similar rate of babies had to drop out of the study (3 on the nCPAP first and 2 on the nHFOV side).

In the end should we really be surprised by the results? I do believe that in the right baby who is about to fail nCPAP a trial of nHFOV may indeed work. By what means I really don’t understand. Is it the fact that the mean airway pressure is generally set higher than on nCPAP in some studies? Could it be the oscillatory vibration being a kind of noxious stimulus that prevents apneic events through irritation of the infant?

While traditional invasive HFOV does a marvelous job of clearing out CO2 I have to wonder how the presence of secretions and a nasopharynx that the oscillatory wave has to avoid (almost like a magic wave that takes a 90 degree turn and then moves down the airway) allows much of any of the wave to reach the distal alveoli. It would be similar to what we know of inhaled steroids being deposited 90 or so percent in the oral cavity and pharynx. There is just a lot of “stuff” in the way from the nostril to the alveolus.

This leads me to my conclusion that if it is pCO2 you are trying to lower, I wouldn’t expect any miracles with nHFOV. Is it totally useless? I don’t think so but for now as a respiratory modality I think for the time being it will continue to be “looking for a place to happen”

by All Things Neonatal | Oct 19, 2017 | BPD, Neonatal, Neonatology, preemie, Prematurity

If you work in Neonatology then chances are you have ordered or assisted with obtaining many chest x-rays in your time. If you look at home many chest x-rays some of our patients get, especially the ones who are with us the longest it can be in the hundreds. I am happy to say the tide though is changing as we move more and more to using other imaging modalities such as ultrasound to replace some instances in which we would have ordered a chest x-ray. This has been covered before on this site a few times; see Point of Care Ultrasound in the NICU, Reducing Radiation Exposure in Neonates: Replacing Radiographs With Bedside Ultrasound. and Point of Care Ultrasound: Changing Practice For The Better in NICU.This post though is about something altogether different.

If you do a test then know what you will do with the result before you order it.

If there is one thing I tend to harp on with students it is to think about every test you do before you order it. If the result is positive how will this help you and if negative what does it tell you as well. In essence the question is how will this change your current management. If you really can’t think of a good answer to that question then perhaps you should spare the infant the poke or radiation exposure depending on what is being investigated. When it comes to the baby born before 30 weeks these infants are the ones with the highest risk of developing chronic lung disease. So many x-rays are done through their course in hospital but usually in response to an event such as an increase in oxygen requirements or a new tube with a position that needs to be identified. This is all reactionary but what if you could do one x-ray and take action based on the result in a prospective fashion?

What an x-ray at 7 days may tell you

How many times have you caught yourself looking at an x-ray and saying out loud “looks like evolving chronic lung disease”. It turns out that Kim et al in their publication Interstitial pneumonia pattern on day 7 chest radiograph predicts bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants.believe that we can maybe do something proactively with such information.

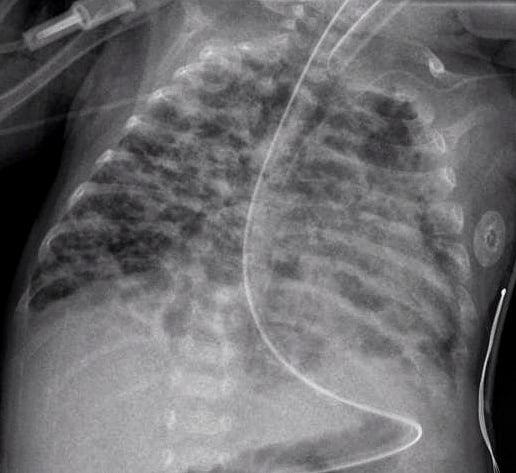

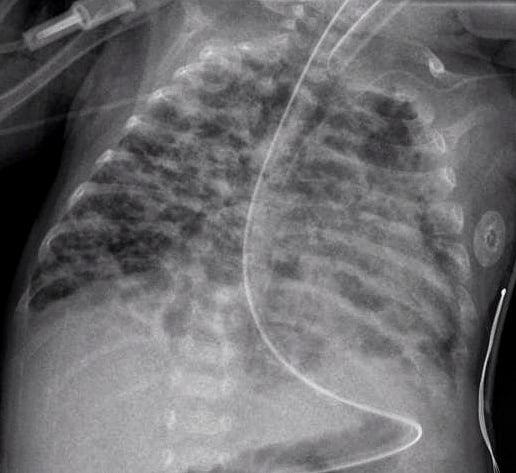

In this study they looked retrospectively at 336 preterm infants weighing less than 1500g and less than 32 weeks at birth. Armed with the knowledge that many infants who have an early abnormal x-ray early in life who go on to develop BPD, this group decided to test the hypothesis that an x-ray demonstrating a pneumonia like pattern at day 7 of life predicts development of BPD.  The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

What do we do with such information?

I suppose the paper tells us something that we have really already known for awhile. Bad lungs early on predict bad lungs at a later date and in particular at 36 weeks giving a diagnosis of BPD. What this study adds if anything is that one can tell quite early whether they are destined to develop this condition or not. The issue then is what to do with such information. The authors suggest that by knowing the x-ray findings this early we can do something about it to perhaps modify the course. What exactly is that though? I guess it is possible that we can use steroids postnatally in this cohort and target such infants as this. I am not sure how far ahead this would get us though as if I had to guess I would say that these are the same infants that more often than not are current recipients of dexamethasone.

Would another dose of surfactant help? The evidence for late surfactant isn’t so hot itself so that isn’t likely to offer much in the way of benefit either.

In the end the truth is I am not sure if knowing concretely that a patient will develop BPD really offers much in the way of options to modify the outcome at this point. Having said that the future may well bring the use of stem cells for the treatment of BPD and that is where I think such information might truly be helpful. Perhaps a screening x-ray at 7 days might help us choose in the future which babies should receive stem cell therapy (should it be proven to work) and which should not. I am proud to say I had a chance to work with a pioneer in this field of research who may one day cure BPD. Dr. Thebaud has written many papers of the subject and if you are looking for recent review here is one Stem cell biology and regenerative medicine for neonatal lung diseases.Do I think that this one paper is going to help us eradicate BPD? I do not but one day this strategy in combination with work such as Dr. Thebaud is doing may lead us to talk about BPD at some point using phrases like “remember when we used to see bad BPD”. One can only hope.

by All Things Neonatal | Sep 28, 2017 | caffeine, preemie, Prematurity

Given that many preterm infants as they near term equivalent age are ready to go home it is common practice to discontinue caffeine sometime between 33-34 weeks PMA. We do this as we try to time the readiness for discharge in terms of feeding, to the desire to see how infants fare off caffeine. In general, most units I believe try to send babies home without caffeine so we do our best to judge the right timing in stopping this medication. After a period of 5-7 days we generally declare the infant safe to be off caffeine and then move on to other issues preventing them from going home to their families. This strategy generally works well for those infants who are born at later gestations but as Rhein LM et al demonstrated in their paper Effects of caffeine on intermittent hypoxia in infants born prematurely: a randomized clinical trial., after caffeine is stopped, the number of intermittent hypoxic (IH) events are not trivial between 35-39 weeks. Caffeine it would seem may still offer some benefit to those infants who seem otherwise ready to discontinue the medication. What the authors noted in this randomized controlled trial was that the difference caffeine made when continued past 34 weeks was limited to reducing these IH events only from 35-36 weeks but the effect didn’t last past that. Why might that have been? Well it could be that the babies after 36 weeks don’t have enough events to really show a difference or it could be that the dose of caffeine isn’t enough by that point. The latter may well be the case as the metabolism of caffeine ramps up during later gestations and changes from a half life greater than a day in the smallest infants to many hours closer to term. Maybe the caffeine just clears faster?

Follow-up Study attempts to answer that very question.

Recognizing the possibility that levels of caffeine were falling too low after 36 weeks the authors of the previous study begun anew to ask the same question but this time looking at caffeine levels in saliva to ensure that sufficient levels were obtained to demonstrate a difference in the outcome of frequency of IH. In this study, they compared the original cohort of patients who did not receive caffeine after planned discontinuation (N=53) to 27 infants who were randomized to one of two caffeine treatments once the decision to stop caffeine was made. Until 36 weeks PMA each patient was given a standard 10 mg/kg of caffeine case and then randomized to two different strategies. The two dosing strategies were 14 mg/kg of caffeine citrate (equals 7 mg/kg of caffeine base) vs 20 mg/kg (10 mg/kg caffeine base) which both started once the patient reached 36 weeks in anticipation of increased clearance. Salivary caffeine levels were measured just prior to stopping the usual dose of caffeine and then one week after starting 10 mg/kg dosing and then at 37 and 38 weeks respectively on the higher dosing. Adequate serum levels are understood to be > 20 mcg/ml and salivary and plasma concentrations have been shown to have a high level of agreement previously so salivary measurement seems like a good approach. Given that it was a small study it is work noting that the average age of the group that did not receive caffeine was 29.1 weeks compared to the caffeine groups at 27.9 weeks. This becomes important in the context of the results in that earlier gestational age patients would be expected to have more apnea which is not what was observed suggesting a beneficial effect of caffeine even at this later gestational age. Each patient was to be monitored with an oximeter until 40 weeks as per unit guidelines.

So does caffeine make a difference once term gestation is reached?

A total of 32 infants were enrolled with 12 infants receiving the 14 mg/kg and 14 the 20 mg/kg dosing. All infants irrespective of assigned group had caffeine concentrations above 20 mcg/mL ensuring that a therapeutic dose had been received. The intent had been to look at babies out to 40 weeks with pulse oximetry even when discharged but owing to drop off in compliance with monitoring for a minimum of 10 hours per PMA week the analysis was restricted to infants at 37 and 38 weeks which still meant extension past 36 weeks as had been looked at already in the previous study. The design of this study then compared infants receiving known therapeutic dosing at this GA range with a previous cohort from the last study that did not receive caffeine after clinicians had determined it was no longer needed.

The outcomes here were measured in seconds per 24 hours of intermittent hypoxia (An IH event was defined as a decrease in SaO2 by ⩾ 10% from baseline and lasting for ⩾5 s). For graphical purposes the authors chose to display the number of seconds oxygen saturation fell below 90% per day and grouped the two caffeine patients together given that the salivary levels in both were therapeutic. As shown a significant difference in events was seen at all gestational ages.

Putting it into context

The scale used I find interesting and I can’t help but wonder if it was done intentionally to provide impact. The outcome here is measured in seconds and when you are speaking about a mean of 1200 vs 600 seconds it sounds very dramatic but changing that into minutes you are talking about 20 vs 10 minutes a day. Even allowing for the interquartile ranges it really is not more than 50 minutes of saturation less than 90% at 36 weeks. The difference of course as you increase in gestation becomes less as well. When looking at the amount of time spent under 80% for the groups at the three different gestational ages there is still a difference but the amount of time at 36, 37 and 38 weeks was 229, 118 and 84 seconds respectively without caffeine (about 4, 2 and 1 minute per day respectively) vs 83, 41, and 22 seconds in the caffeine groups. I can’t help but think this is a case of statistical significance with questionable clinical significance. The authors don’t indicate that any patients were readmitted with “blue spells” who were being monitored at home which then leaves the sole question in my mind being “Do these brief periods of hypoxemia matter?” In the absence of a long-term follow-up study I would have to say I don’t know but while I have always been a fan of caffeine I am just not sure.

Should we be in a rush to stop caffeine? Well, given that the long term results of the CAP study suggest the drug is safe in the preterm population I would suggest there is no reason to be concerned about continuing caffeine a little longer. If the goal is getting patients home and discharging on caffeine is something you are comfortable with then continuing past 35 weeks is something that may have clinical impact. At the very least I remain comfortable in my own practice of not being in a rush to stop this medication and on occasion sending a patient home with it as well.

by All Things Neonatal | Sep 13, 2017 | Neonatal, Neonatology, newborn, preemie, Prematurity, resuscitation, ventilation

We can always learn and we can always do better. At least that is something that I believe in. In our approach to resuscitating newborns one simple rule is clear. Fluid must be replaced by air after birth and the way to oxygenate and remove CO2 is to establish a functional residual capacity. The functional residual capacity is the volume of air left in the lung after a tidal volume of air is expelled in a spontaneously breathing infant and is shown in the figure. Traditionally, to establish this volume in a newborn who is apneic, you begin PPV or in the spontaneously breathing baby with respiratory distress provide CPAP to help inflate the lungs and establish FRC.

Is there another way?

Something that has been discussed now for some time and was commented on in the most recent version of NRP was the concept of using sustained inflation (SI) to achieve FRC. I have written about this topic previously and came to a conclusion that it wasn’t quite ready for prime time yet in the piece Is It Time To Use Sustained Lung Inflation In NRP?

The conclusion as well in the NRP textbook was the following:

“There are insufficient data regarding short and long-term safety and the most appropriate duration and pressure of inflation to support routine application of sustained inflation of greater than 5 seconds’ duration to the transitioning newborn (Class IIb, LOE B-R). Further studies using carefully designed protocols are needed”

So what now could be causing me to revisit this concept? I will be frank and admit that whenever I see research out of my old unit in Edmonton I feel compelled to read it and this time was no different. The Edmonton group continues to do wonderful work in the area of resuscitation and expand the body of literature in such areas as sustained inflation.

Can you predict how much of a sustained inflation is needed?

This is the crux of a recent study using end tidal CO2 measurement to determine whether the lung has indeed established an FRC or not. Dr. Schmolzer’s group in their paper (Using exhaled CO2 to guide initial respiratory support at birth: a randomised controlled trial) used end tidal CO2 levels above 20 mmHg to indicate that FRC had been established. If you have less CO2 being released the concept would be that the lung is actually not open. There are some important numbers in this study that need to be acknowledged. The first is the population that they looked at which were infants under 32 6/7 weeks and the second is the incidence of BPD (need for O2 or respiratory support at 36 weeks) which in their unit was 49%. This is a BIG number as in comparison for infants under 1500g our own local incidence is about 11%. If you were to add larger infants closer to 33 weeks our number would be lower due to dilution. With such a large number though in Edmonton it allowed them to shoot for a 40% reduction in BPD (50% down to 30%). To accomplish this they needed 93 infants in each group to show a difference this big.

So what did they do?

For this study they divided the groups in two when the infant wouldn’t breathe in the delivery room. The SI group received a PIP of 24 using a T-piece resuscitator for an initial 20 seconds. If the pCO2 as measured by the ETCO2 remained less than 20 they received an additional 10 seconds of SI. In the PPV group after 30 seconds of PPV the infants received an increase of PIP if pCO2 remained below 20 or a decrease in PIP if above 20. In both arms after this phase of the study NRP was then followed as per usual guidelines.

The results though just didn’t come through for the primary outcome although ventilation did show a difference.

| Outcome |

SI |

PPV |

p |

| BPD |

23% |

33% |

0.09 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (hrs) |

63 |

204 |

0.045 |

The reduction in hours of ventilation was impressive although no difference in BPD was seen. The problem though with all of this is what happened after recruitment into the study. Although they started with many more patients than they needed, by the end they had only 76 in the SI group and 86 in the PPV group. Why is this a problem? If you have less patients than you needed based on the power calculation then you actually didn’t have enough patients enrolled to show a difference. The additional compounding fact here is that of the Hawthorne Effect. Simply put, patients who are in a study tend to do better by being in a study. The observed rate of BPD was 33% during the study. If the observed rate is lower than expected when the power calculation was done it means that the number needed to show a difference was even larger than the amount they originally thought was needed. In the end they just didn’t have the numbers to show a difference so there isn’t much to conclude.

What I do like though

I have a feeling or a hunch that with a larger sample size there could be something here. Using end tidal pCO2 to determine if the lung is open is in and of itself I believe a strategy to consider whether giving PPV or one day SI. We already use colorimetric devices to determine ETT placement but using a quantitative measure to ascertain the extent of open lung seems promising to me. I for one look forward to the continued work of the Neonatal Resuscitation–Stabilization–Triage team (RST team) and congratulate them on the great work that they continue doing.

by All Things Neonatal | Sep 7, 2017 | preemie, Prematurity, ventilation

A grenade was thrown this week with the publication of the Australian experience comparing three epochs of 1991-92, 1997 and 2005 in terms of long term respiratory outcomes. The paper was published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine; Ventilation in Extremely Preterm Infants and Respiratory Function at 8 Years. This journal alone gives “street cred” to any publication and it didn’t take long for other news agencies to notice such as Med Page Today. The claim of the paper is that the modern cohort has fared worse in the long run. This has got to be alarming for anyone reading this! As the authors point out, over the years that are being compared rates of antenatal steroid use increased, surfactant was introduced and its use became more widespread and a trend to using non-invasive ventilation began. All of these things have been associated with better short term outcomes. Another trend was declining use of post-natal steroids after 2001 when alarms were raised about the potential harm of administering such treatments.

Where then does this leave us?

I suppose the first thing to do is to look at the study and see if they were on the mark. To evaluate lung function the study looked at markers of obstructive lung disease at 8 years of age in survivors from these time periods. All babies recruited were born between 22-27 completed weeks so were clearly at risk of long term injury. Measurements included FEV1, FVC, FVC:FEV1 and FEF 25-75%. Of the babies measured the only two significant findings were in the FEV1 and ratio of FEV1:FVC. The former showed a drop off comparing 1997 to 2005 while the latter was worse in 2005 than both epochs.

| Variable |

1991-92 |

1997 |

2005 |

| %predicted value |

N=183 |

N=112 |

N=123 |

| FEV1 |

87.9+/-13.4 |

92.0+/-15.7 |

85.4+/-14.4 |

| FEV1:FVC |

98.3+/-10 |

96.8+/-10.1 |

93.4+/-9.2 |

This should indeed cause alarm. Babies born in a later period when we thought that we were doing the right things fared worse. The authors wonder if perhaps a strategy of using more CPAP may be a possible issue. Could the avoidance of intubation and dependence on CPAP for longer periods actually contribute to injury in some way? An alternative explanation might be that the use of continuous oximetry is to blame. Might the use of nasal cannulae with temporary rises in O2 expose the infant to oxygen toxicity?

There may be a problem here though

Despite everyone’s best efforts survival and/or BPD as an outcome has not changed much over the years. That might be due to a shift from more children dying to more children living with BPD. Certainly in our own centre we have seen changes in BPD at 36 weeks over time and I suspect other centres have as well. With concerted efforts many centres report better survival of the smallest infants and with that they may survive with BPD. The other significant factor here is after the extreme fear of the early 2000s, use of postnatal steroids fell off substantially. This study was no different in that comparing the epochs, postnatal glucocorticoid use fell from 40 and 46% to 23%. One can’t ignore the possibility that the sickest of the infants in the 2005 cohort would have spent much more time on the ventilator that their earlier counterparts and this could have an impact on the long term lung function.

Another question that I don’t think was answered in the paper is the distribution of babies at each gestational age. Although all babies were born between 22-27 weeks gestational age, do we know if there was a skewing of babies who survived to more of the earlier gestations as more survived? We know that in the survivors the GA was not different so that is reassuring but did the sickest possible die more frequently leaving healthier kids in the early cohorts?

This bigger issue interestingly is not mentioned in the paper. Looking at the original cohorts there were 438 in the first two year cohort of which 203 died yielding a survival of 54% while in 1997 survival increased to 70% and in 2005 it was 65%. I can’t help but wonder if the drop in survival may have reflected a few more babies at less than 24 weeks being born and in addition the holding of post natal steroids leading to a few more deaths. Either way, there are enough questions about the cohorts not really being the same that I think we have to take the conclusions of this paper with a grain of salt.

It is a sensational suggestion and one that I think may garner some press indeed. I for one believe strongly though as I see our rates of BPD falling with the strategies we are using that when my patients return at 8 years for a visit they will be better off due to the strategies we are using in the current era. Having said that we do have so much more to learn and I look forward to better outcomes with time!

by All Things Neonatal | Aug 23, 2017 | donor milk, Neonatology, nutrition, preemie, Prematurity

Exclusive human milk (EHM) diets using either mother’s own milk or donor milk plus a human based human milk fortifier have been the subject of many papers over the last few years. Such papers have demonstrated reductions is such outcomes as NEC, length of stay, days of TPN and number of times feedings are held due to feeding intolerance to name just a few outcomes. There is little argument that a diet for a human child composed of human milk makes a great deal of sense. Although we have come to rely on bovine sources of both milk and fortifier when human milk is unavailable I am often reminded that bovine or cow’s milk is for baby cows.

Challenges with using an exclusive human milk diet.

While it makes intuitive sense to strive for an exclusive human milk diet, there are barriers to the same. Low rates of maternal breastfeeding coupled with limited or no exposure to donor breast milk programs are a clear impediment. Even if you have those first two issues minimized through excellent rates of breast milk provision, there remains the issue of whether one has access to a human based fortifier to achieve the “exclusive” human milk diet.

The “exclusive” approach is one that in the perfect world we would all strive for but in times of fiscal constraint there is no question that any and all programs will be questioned from a cost-benefit standpoint. The issue of cost has been addressed previously by Ganapathy et al in their paper Costs of Necrotizing Enterocolitis and Cost-Effectiveness of Exclusively Human Milk-Based Products in Feeding Extremely Premature Infants. The authors were able to demonstrate that choosing an exclusive human milk diet is cost effective in addition to the benefits observed clinically from such a diet. In Canada where direct costs are more difficult to visualize and a reduction in nursing staff per shift brings about the most direct savings, such an argument becomes more difficult to achieve.

Detractors from the EHM diet argue that we have been using bovine fortification from many years and the vast majority of infants regardless of gestational age have little challenge with it. Growth rates of 15-20 g/kg/d are achievable using such fortification so why would you need to treat all patients with an EHM diet?

A Rescue Approach

In our own centre we were faced with these exact questions and developed a rescue approach. The rescue was designed to identify those infants who seemed to have a clear intolerance to bovine fortifier as all of the patients we care for under 1250g receive either mother’s own or donor milk. The approach used was as follows:

A. < 27 weeks 0 days or < 1250 g

i. 2 episode of intolerance to HMF

ii. Continue for 2 weeks

This month we published our results from using this targeted rescue approach in Winnipeg, Human Based Human Milk Fortifier as Rescue Therapy in Very Low Birth Weight Infants Demonstrating Intolerance to Bovine Based Human Milk Fortifier with Dr. Sandhu being the primary author (who wrote this as a medical student with myself and others. We are thrilled to share our experience and describe the cases we have experienced in detail in the paper. Suffice to say though that we have identified value in such an approach and have now modified our current approach based on this experience to the following protocol for using human derived human milk fortifier in our centre to the current:

A. < 27 weeks 0 days or < 1250 g

i. 1 episode of intolerance to HMF

ii. Continue for 4 weeks

B. ≥ 27 week 0 days or ≥ 750g

i. 2 episodes of intolerance to HMF

ii. Continue for 4 weeks or to 32 weeks 0 days whichever comes sooner

We believe given our current contraints, this approach will reduce the risk of NEC, feeding intolerance and ultimately length of stay while being fiscally prudent in these challenging times. Given the interest at least in Canada with what we have been doing here in Winnipeg and with the publication of our results it seemed like the right time to share this with you. Whether this approach or one that is based on providing human based human milk fortifier to all infants <1250g is a matter of choice for each institution that chooses to use a product such as Prolacta. In no way is this meant to be a promotional piece but rather to provide an option for those centres that would like to use such products to offer an EHM diet but for a variety of reasons have opted not to provide it to all.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.