Over the last number of years clinicians have sought more and more to limit the experience of babies to painful stimuli. In the area of surfactant administration this has focused on “less invasive” strategies such as use of small catheters while on CPAP (LISA or MIST) and surfactant via LMA or Surfactant Administration Through Laryngeal or Supraglottic Airways (SALSA) as it is sometimes known. Intubation Surfactant Extubation (INSURE) while not generally included in the less invasive approach is to a degree fitting since it involves at least intubating for a very brief period after surfactant is administered. SALSA has been growing in popularity due to its “extreme” non-invasiveness since babies are receiving surfactant without instrumentation of the airway at all. It should come as no surprise then that head to head comparisons will be done to determine which should be reigned king!

The Contenders

A group out of Albany, NY has looked at SALSA vs INSURE before in which they used morphine for premedication prior to the procedure. You might ask why any premedication is needed at all but I would suggest that covering one’s airway and dripping liquid into it might cause some irritation so why not keep them calm. The authors in their paper Randomized trial of laryngeal mask airway versus endotracheal intubation for surfactant delivery found a high rate of failure in the intubation arm which more than likely was attributable to the respiratory depressive effect of the same.

This time around in the current paper Randomized Trial of Surfactant Therapy via Laryngeal Mask Airway Versus Brief Tracheal Intubation in Neonates Born Preterm they switched to remifentanil for its brief duration of action. Babies in the SALSA arm received that drug while those in the ETT group received atropine as well. The authors included infants born from 27 weeks to 36 weeks gestation who were larger than 800g at birth. This was a non-inferiority trial with the primary outcome being Our primary outcome was failure of surfactant therapy to prevent the need for invasive mechanical ventilation or its surrogate indicators, namely, more than 2 doses of surfactant therapy, sustained need for FiO2 >0.60 to maintain target O2 saturations, or a second dose of surfactant within 8 hours of the first dose.

Surfactant redosing criteria were the same for both groups: FiO2 >0.60 or FiO2 >0.30 with clinical signs of worsening RDS. If surfactant needed to be given a second time it was via intubation. The decision to ultimately intubate though was in the hands of the practitioners.

Unfortunately, the trial was stopped after only 51 patients were enrolled into the LMA and 42 into the INSURE groups respectively. Randomization was by block design and the authors were looking for 130 patients per group so they fell far short of that. The reasons for falling short were interesting as they demonstrate one of the challenges of research and changing beliefs. At the start of the trial there was equipoise among practitioners with respect to the two modes of surfactant delivery but part way through people preferred SALSA. The authors changed the randomization to try and deal with that to a 2:1 favoring SALSA but with the combination of that and COVID they had to stop. They did manage to get enough though to determine the primary outcome in spite of this.

What did they find in the end?

Well first of all it is worth noting that there were no differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups. As it turns out, while the numbers were small it didn’t seem to lead to an unbalancing of groups.

With respect to inferiority the finding was that it was in fact not inferior as per the figure below.

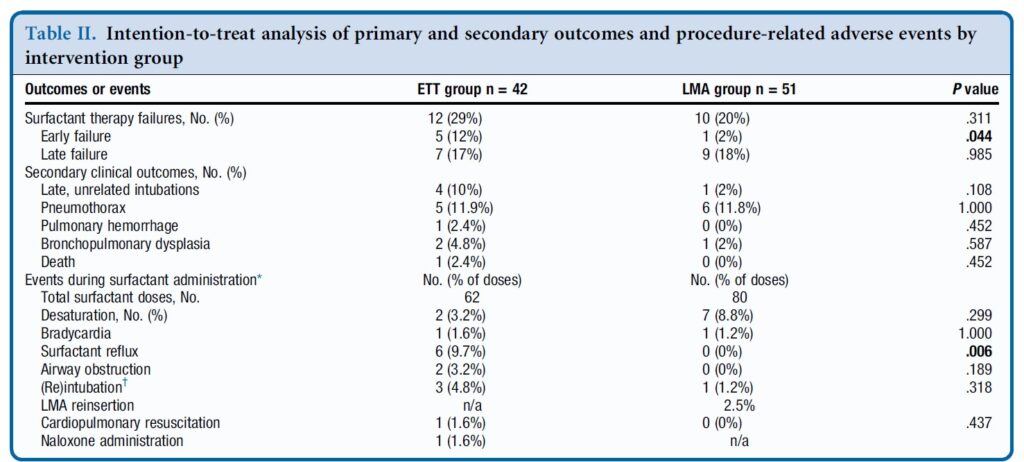

In table 2 some interesting findings emerge

Early failure of surfactant which was defined as within 1 hour of surfactant administration was found to be significantly increased in the intubation group. Late failure through at 5 days of age was not any different. An early failure is suggestive of the procedure not working to deliver the surfactant. When you look at the bottom half of table 2 the answer may be there. As part of the planned procedure the authors aspirated a gastric tube after surfactant administration to ensure that it went to the right place. There was no difference in surfactant volume aspirated via this route. There was however 9.7% of infants in the ETT group that experienced reflux in the ETT vs zero with observed reflux in the SALSA group (in the mouth perhaps?). Is surfactant without PPV better tolerated maybe?

There was a trend overall to more failures in the ETT arm although this was not found to be significant either in the intention to treat or per protocol analysis.

Where do we go from here?

First off it is important to look at who was chosen for this strategy. You may have noticed that there were no micropreemies in this trial. The reason for this is likely two-fold. The first is that prior trials on SALSA have found it doesn’t work as well to prevent intubations in babies below 27 weeks. This is very similar to the findings of studies using aerosolized surfactant. It may well be that there just isn’t enough of the total dose getting to the alveoli. If you can get some of the dose in deep into the lung for those with less severe RDS it may work ok for those babies. The second reason likely has to do with using LMAs in those in that weight range as they generally are designed for larger preemies although I understand smaller ones are becoming more readily available.

The second point is that this was not a blinded study. This could have become an issue as the authors acknowledge that there was a growing institutional preference for SALSA as the study went on. If the Neonatologist subconsciously believes it is better, might that have influenced some of the decisions to intubate again since one of the criteria was “clinical signs of worsening RDS”. It is quite possible this could have led to a few more intubations in the INSURE group for repeat doses. We can’t prove that but it is a weakness of the study.

At the very least it can be argued that the use of SALSA works as a small percentage overall failed the procedure. The largest groups of infants though were above 29 weeks so we also might not expect a high rate of failure after one dose though. It works but how well is tough to say.

Where I think this study is really important though is what it tells us for centers in particular who don’t intubate as often. Intubation is a skill that is declining in opportunity, both because of a turn to more use of non-invasive support as a primary mode of treatment. It also has become scarcer at an individual level due to there being more practitioners who can perform the skill. Having an option to use SALSA for those who aren’t as comfortable with intubation will no doubt be of much interest to many in this situation.

What is no doubt going to come next is the LISA/MIST vs SALSA trials. I hope that in the future pain scores are included in these sorts of analyses to really determine if in being less invasive we are also ensuring that we are also not undertreating discomfort. I suppose the lesson being learned from all of this is that less very well may be more.

Thanks for discussing this study. But really wonder

– there is a typo about the study group 27 to 36 weeks?

– InSurE with reflux?! I mean with good larynx fitting ETT!? I don’t think it is a common issue in practice?

– we defined characteristics of both groups by many things, but none of them can tell who were essentially worse, what FIO2 exactly was required to maintain So2, and any imaging scales (like LUS score) which may lead to some confusion explaining the failure rate difference or even the non-inferiority!?

No typo my friend and thanks for reading

Here were the criteria for surfactant redosing. No LUS

“Surfactant redosing criteria were the same for both groups:

FiO2 >0.60 or FiO2 >0.30 with clinical signs of worsening

RDS. Surfactant redosed within 8 hours of initial dose was

administered via ETT for all study patients; if it was redosed

>8 hours after initial dose, the second dose was given by the

same method as the initial dose; third or subsequent doses

were given via ETT for both groups”

Thanks a lot for the reply, but what I meant:

– the typo as in the study included 27 till 36 weeks. But in your review written as 27 to 26 ?

– for the FIO2 factor, I meant, giving surfactant with FIO2 100% is different from giving it with FIO2 60%. and same for the clinical symptoms group: giving surfactant with FIO2 of 60 or 70% is different from administering it to an FIO2 30% . (because naturally this implies how bad the lung initially are, which may lead to higher failure rate)!

thanks for catching that. Just changed it

Thank you for sharing. I have a question. Which kind of LMA did the authors use for this trial? Because I thought there were not for babies < 32 weeks. In my unit I have been doing since 2015 LISA for all preterm baby…23 weeks as well with good outcome regarding BPD…and in the context of less invasive having alternative way would be interesting.

It would have been a 1 I believe. For most places that is all that is available although I have heard of a 0.5. Some people are using them below a 1 kg weight