by All Things Neonatal | Oct 19, 2017 | BPD, Neonatal, Neonatology, preemie, Prematurity

If you work in Neonatology then chances are you have ordered or assisted with obtaining many chest x-rays in your time. If you look at home many chest x-rays some of our patients get, especially the ones who are with us the longest it can be in the hundreds. I am happy to say the tide though is changing as we move more and more to using other imaging modalities such as ultrasound to replace some instances in which we would have ordered a chest x-ray. This has been covered before on this site a few times; see Point of Care Ultrasound in the NICU, Reducing Radiation Exposure in Neonates: Replacing Radiographs With Bedside Ultrasound. and Point of Care Ultrasound: Changing Practice For The Better in NICU.This post though is about something altogether different.

If you do a test then know what you will do with the result before you order it.

If there is one thing I tend to harp on with students it is to think about every test you do before you order it. If the result is positive how will this help you and if negative what does it tell you as well. In essence the question is how will this change your current management. If you really can’t think of a good answer to that question then perhaps you should spare the infant the poke or radiation exposure depending on what is being investigated. When it comes to the baby born before 30 weeks these infants are the ones with the highest risk of developing chronic lung disease. So many x-rays are done through their course in hospital but usually in response to an event such as an increase in oxygen requirements or a new tube with a position that needs to be identified. This is all reactionary but what if you could do one x-ray and take action based on the result in a prospective fashion?

What an x-ray at 7 days may tell you

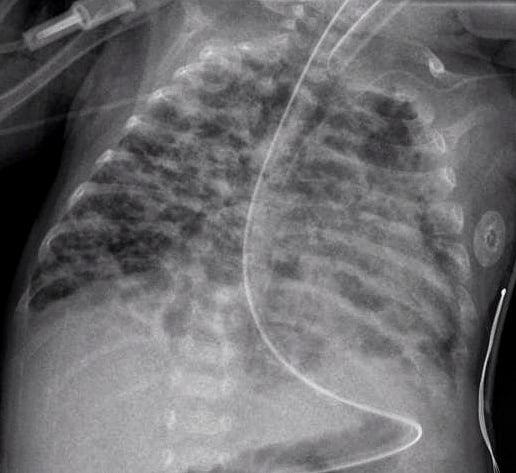

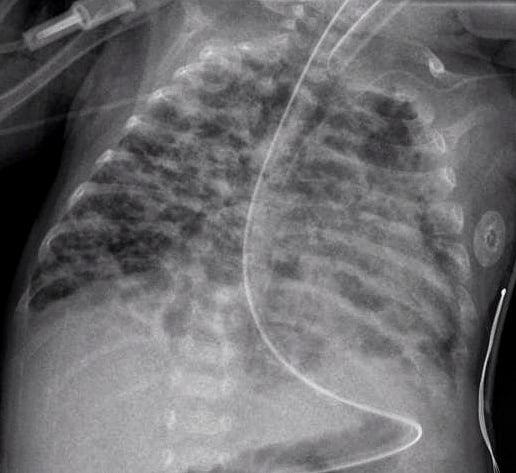

How many times have you caught yourself looking at an x-ray and saying out loud “looks like evolving chronic lung disease”. It turns out that Kim et al in their publication Interstitial pneumonia pattern on day 7 chest radiograph predicts bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants.believe that we can maybe do something proactively with such information.

In this study they looked retrospectively at 336 preterm infants weighing less than 1500g and less than 32 weeks at birth. Armed with the knowledge that many infants who have an early abnormal x-ray early in life who go on to develop BPD, this group decided to test the hypothesis that an x-ray demonstrating a pneumonia like pattern at day 7 of life predicts development of BPD.  The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

What do we do with such information?

I suppose the paper tells us something that we have really already known for awhile. Bad lungs early on predict bad lungs at a later date and in particular at 36 weeks giving a diagnosis of BPD. What this study adds if anything is that one can tell quite early whether they are destined to develop this condition or not. The issue then is what to do with such information. The authors suggest that by knowing the x-ray findings this early we can do something about it to perhaps modify the course. What exactly is that though? I guess it is possible that we can use steroids postnatally in this cohort and target such infants as this. I am not sure how far ahead this would get us though as if I had to guess I would say that these are the same infants that more often than not are current recipients of dexamethasone.

Would another dose of surfactant help? The evidence for late surfactant isn’t so hot itself so that isn’t likely to offer much in the way of benefit either.

In the end the truth is I am not sure if knowing concretely that a patient will develop BPD really offers much in the way of options to modify the outcome at this point. Having said that the future may well bring the use of stem cells for the treatment of BPD and that is where I think such information might truly be helpful. Perhaps a screening x-ray at 7 days might help us choose in the future which babies should receive stem cell therapy (should it be proven to work) and which should not. I am proud to say I had a chance to work with a pioneer in this field of research who may one day cure BPD. Dr. Thebaud has written many papers of the subject and if you are looking for recent review here is one Stem cell biology and regenerative medicine for neonatal lung diseases.Do I think that this one paper is going to help us eradicate BPD? I do not but one day this strategy in combination with work such as Dr. Thebaud is doing may lead us to talk about BPD at some point using phrases like “remember when we used to see bad BPD”. One can only hope.

by All Things Neonatal | Sep 13, 2017 | Neonatal, Neonatology, newborn, preemie, Prematurity, resuscitation, ventilation

We can always learn and we can always do better. At least that is something that I believe in. In our approach to resuscitating newborns one simple rule is clear. Fluid must be replaced by air after birth and the way to oxygenate and remove CO2 is to establish a functional residual capacity. The functional residual capacity is the volume of air left in the lung after a tidal volume of air is expelled in a spontaneously breathing infant and is shown in the figure. Traditionally, to establish this volume in a newborn who is apneic, you begin PPV or in the spontaneously breathing baby with respiratory distress provide CPAP to help inflate the lungs and establish FRC.

Is there another way?

Something that has been discussed now for some time and was commented on in the most recent version of NRP was the concept of using sustained inflation (SI) to achieve FRC. I have written about this topic previously and came to a conclusion that it wasn’t quite ready for prime time yet in the piece Is It Time To Use Sustained Lung Inflation In NRP?

The conclusion as well in the NRP textbook was the following:

“There are insufficient data regarding short and long-term safety and the most appropriate duration and pressure of inflation to support routine application of sustained inflation of greater than 5 seconds’ duration to the transitioning newborn (Class IIb, LOE B-R). Further studies using carefully designed protocols are needed”

So what now could be causing me to revisit this concept? I will be frank and admit that whenever I see research out of my old unit in Edmonton I feel compelled to read it and this time was no different. The Edmonton group continues to do wonderful work in the area of resuscitation and expand the body of literature in such areas as sustained inflation.

Can you predict how much of a sustained inflation is needed?

This is the crux of a recent study using end tidal CO2 measurement to determine whether the lung has indeed established an FRC or not. Dr. Schmolzer’s group in their paper (Using exhaled CO2 to guide initial respiratory support at birth: a randomised controlled trial) used end tidal CO2 levels above 20 mmHg to indicate that FRC had been established. If you have less CO2 being released the concept would be that the lung is actually not open. There are some important numbers in this study that need to be acknowledged. The first is the population that they looked at which were infants under 32 6/7 weeks and the second is the incidence of BPD (need for O2 or respiratory support at 36 weeks) which in their unit was 49%. This is a BIG number as in comparison for infants under 1500g our own local incidence is about 11%. If you were to add larger infants closer to 33 weeks our number would be lower due to dilution. With such a large number though in Edmonton it allowed them to shoot for a 40% reduction in BPD (50% down to 30%). To accomplish this they needed 93 infants in each group to show a difference this big.

So what did they do?

For this study they divided the groups in two when the infant wouldn’t breathe in the delivery room. The SI group received a PIP of 24 using a T-piece resuscitator for an initial 20 seconds. If the pCO2 as measured by the ETCO2 remained less than 20 they received an additional 10 seconds of SI. In the PPV group after 30 seconds of PPV the infants received an increase of PIP if pCO2 remained below 20 or a decrease in PIP if above 20. In both arms after this phase of the study NRP was then followed as per usual guidelines.

The results though just didn’t come through for the primary outcome although ventilation did show a difference.

| Outcome |

SI |

PPV |

p |

| BPD |

23% |

33% |

0.09 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (hrs) |

63 |

204 |

0.045 |

The reduction in hours of ventilation was impressive although no difference in BPD was seen. The problem though with all of this is what happened after recruitment into the study. Although they started with many more patients than they needed, by the end they had only 76 in the SI group and 86 in the PPV group. Why is this a problem? If you have less patients than you needed based on the power calculation then you actually didn’t have enough patients enrolled to show a difference. The additional compounding fact here is that of the Hawthorne Effect. Simply put, patients who are in a study tend to do better by being in a study. The observed rate of BPD was 33% during the study. If the observed rate is lower than expected when the power calculation was done it means that the number needed to show a difference was even larger than the amount they originally thought was needed. In the end they just didn’t have the numbers to show a difference so there isn’t much to conclude.

What I do like though

I have a feeling or a hunch that with a larger sample size there could be something here. Using end tidal pCO2 to determine if the lung is open is in and of itself I believe a strategy to consider whether giving PPV or one day SI. We already use colorimetric devices to determine ETT placement but using a quantitative measure to ascertain the extent of open lung seems promising to me. I for one look forward to the continued work of the Neonatal Resuscitation–Stabilization–Triage team (RST team) and congratulate them on the great work that they continue doing.

by All Things Neonatal | Feb 15, 2017 | outcome, Uncategorized

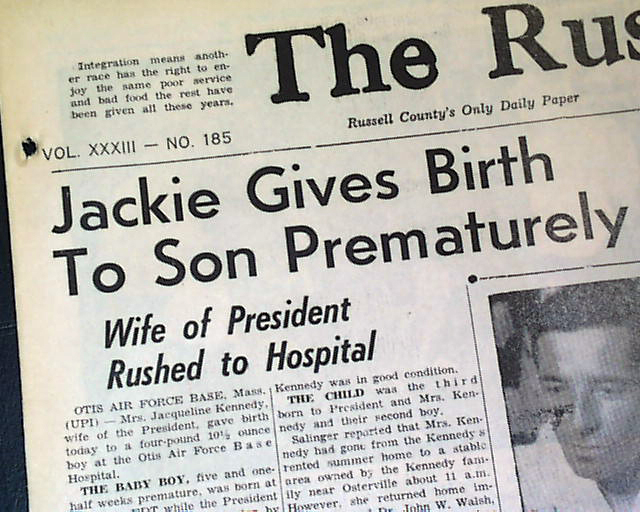

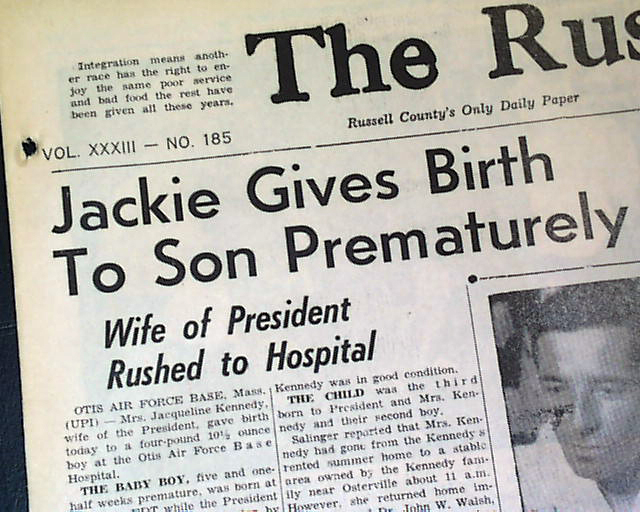

As a Neonatologist I doubt there are many topics discussed over coffee more than BPD. It is our metric by which we tend to judge our performance as a team and centre possibly more than any other. This shouldn’t be that surprising. The dawn of Neonatology was exemplified by the development of ventilators capable of allowing those with RDS to have a chance at survival.  As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.

As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.

The disease has changed to one where many factors such as oxygen and chorioamnionitis combine to cause arrest of alveolar development along with abnormal branching and thickening of the pulmonary vasculature to create insufficient air/blood interfaces +/- pulmonary hypertension. This new form is prevalent in units across the world and generally appears as hazy lungs minus the cystic change for the most part seen previously. Defining when to diagnose BPD has been a challenge. Is it oxygen at 28 days, 36 weeks PMA, x-ray compatible change or something else? The 2000 NIH workshop on this topic created a new approach to defining BPD which underwent validation towards predicting downstream pulmonary morbidity in follow-up in 2005. That was over a decade ago and the question is whether this remains relevant today.

Benchmarking

I don’t wish to make light of the need to track our rates of BPD but at times I have found myself asking “is this really important?” There are a number of reasons for saying this. A baby who comes off oxygen at 36 weeks and 1 day is classified as having BPD while the baby who comes off at 35 6/7 does not. Are they really that different? Is it BPD that is keeping our smallest babies in hospital these days? For the most part no. Even after they come off oxygen and other supports it is often the need to establish feeding or adequate weight prior to discharge that delays things these days. Given that many of our smallest infants also have apnea long past 36 weeks PMA we have all seen babies who are free of oxygen at 38 weeks who continue to have events that keep them in hospital. In short while we need to be careful to minimize lung injury and the consequences that may follow the same, does it matter if a baby comes off O2 at 36, 37 or 38 weeks if they aren’t being discharged due to apnea or feeding issues? It does matter for benchmarking purposes as one unit will use this marker to compare themselves against another in terms of performance. Is there something more though that we can hope to obtain?

When does BPD matter?

The real goal in preventing BPD or at least minimizing respiratory morbidity of any kind is to ensure that after discharge from the NICU we are sending out the healthiest babies we can into the community. Does a baby at 36 weeks and one day free of O2 and other support have a high risk of coming back to the hospital after discharge or might it be that those that are even older when they free of such treatments may be worse off after discharge. The longer it takes to come off support one would think, the more fragile you might be. This was the goal of an important study just published entitled Revisiting the Definition of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Effect of Changing Panoply of Respiratory Support for Preterm Neonates. This work is yet another contribution to the pool of knowledge from the Canadian Neonatal Network. In short this was a retrospective cohort study of 1503 babies born at <29 weeks GA who were assessed at 18-21 months of age. The outcomes were serious respiratory morbidity defined as one of:

(1) 3 or more rehospitalizations after NICU discharge owing to respiratory problems (infectious or noninfectious);

(2) having a tracheostomy

(3) using respiratory monitoring or support devices at home such as an apnea monitor

or pulse oximeter

(4) being on home oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure at the time of assessment

While neurosensory impairment being one of:

(1) moderate to severe cerebral palsy (Gross Motor Function Classification System ≥3)

(2) severe developmental delay (Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler

Development Third Edition [Bayley III] composite score <70 in either cognitive, language, or motor domains)

3) hearing aid or cochlear implant use

(4) bilateral severe visual impairment

What did they find?

The authors looked at 6 definitions of BPD and applied examined how predictive they were of these two outcomes. The combination of oxygen and/or respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA had the greatest capacity to predict this composite outcome. It was the secondary analysis though that peaked my interest. Once the authors identified the best predictor of adverse outcome they sought to examine the same combination of respiratory support and/oxygen at gestational ages from 34 -44 weeks PMA. The question here was whether the use of an arbitrary time point of 36 weeks is actually the best number to use when looking at these longer term outcomes. Great for benchmarking but is it great for predicting outcome?

It turns out the point in time with the greatest likelihood of predicting occurrence of serious respiratory morbidity is 40 weeks and not 36 weeks. Curiously, beyond 40 weeks it becomes less predictive. With respect to neurosensory impairment there is no real difference at any gestational age from 34-44 weeks PMA.

From the perspective of what we tell parents these results have some significance. If they are to be believed (and this is a very large sample) then the infant who remains on O2 at 37 weeks but is off by 38 or 39 weeks will likely fair better than the baby who remains on O2 or support at 40 weeks. It also means that the risk of neurosensory impairment is largely set in place if the infant born at < 29 weeks remains on O2 or support beyond 33 weeks. Should this surprise us? Maybe not. A baby who is on such support for over 5 weeks is sick and as a result the damage to the developing brain from O2 free radical damage and/or exposure to chorioamnionitis or sepsis is done.

It will be interesting to see how this study shapes the way we think about BPD. From a neurosensory standpoint striving to remove the need for support by 34 weeks may be a goal worth striving for. Failure to do so though may mean that we at least have some time to reduce the risk of serious respiratory morbidity after discharge.

Thank you to the CNN for putting out what I am sure will be a much discussed paper in the months to come.

by All Things Neonatal | Feb 8, 2017 | Neonatal, Neonatology, outcome, preemie, Prematurity

Positive pressure ventilation puts infants at risk of developing chronic lung disease (CLD). Chronic lung disease in turn has been linked many times over, as a risk for long term impacts on development. So if one could reduce the amount of positive pressure breaths administered to a neonate over the course of their hospital stay, that should reduce the risk of CLD and by extension developmental impairment. At least that is the theory. Around the start of my career in Neonatology one publication that carried a lot of weight in academic circles was the Randomized Trial of Permissive Hypercapnia in Preterm Infants which randomized 49 surfactant treated infants to either a low (35-45) or high (45-55) PCO2 target with the thought being that allowing for a higher pCO2 should mean that lower settings can be used. Lower settings on a ventilator would lead to less lung damage and therefore less CLD and in turn better outcomes. The study in question did show that the primary outcome was indeed different with almost a 75% reduction in days of ventilation and with that the era of permissive hypercapnia was born.

The Cochrane Weigh in

In 2001 a systematic review including this and another study concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support the strategy in terms of a benefit to death or chronic lung disease. Despite this lack of evidence and a recommendation from the Cochrane group that permissive hypercapnia be used only in the context of well designed trials the practice persisted and does so to this day in many places. A little lost in this discussion is that while the end point above was not different there may still be a benefit of shorter term ventilation.

A modern cohort

It would be unwise to ignore at this point that the babies of the late 90s are different that the ones in the current era. Surfactant and antenatal steroid use are much more prevalent now. Ventilation strategies have shifted to volume as opposed to pressure modes in many centres with a shift to early use of modalities such as high frequency ventilation to spare infants the potential harm of either baro or volutrauma. Back in 2015 the results of the PHELBI trial were reported Permissive hypercapnia in extremely low birthweight infants (PHELBI): a randomised controlled multicentre trial. This large trial of 359 patients randomized to a high or low target pCO2 again failed to show any difference in outcomes in terms of the big ones “death or BPD, mortality alone, ROP, or severe IVH”. What was interesting about this study was that they did not pick one unified target for pCO2 but rather set different targets as time went on reflecting that with time HCO3 rises so what matters more is maintaining a minimum pH rather than targeting a pCO2 alone which als0 reflects at least our own centre’s practice. There is a fly in the ointment here though and that is that the control group has a fault (at least in my eyes)

| Day of life |

Low Target |

High Target |

| 1-3 |

40-50 |

55-65 |

| 4-6 |

45-55 |

60-70 |

| 7-14 |

50-60 |

65-75 |

In the original studies of permissive hypercapnia the comparison was of a persistent attempt to keep normal pCO2 vs allowing the pCO2 to drift higher. Although I may get some argument on this point, what was done in this study was to compare two permissive hypercapnia ranges to each other. If it is generally accepted that a normal pCO2 is 35-45 mmHg then none of these ranges in the low target were that at all.

How did these babies do in the long run?

The two year follow-up for this study was published in the last month; Neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low birthweight infants randomised to different PCO2 targets: the PHELBI follow-up study. At the risk of sounding repetitive the results of Bayley III developmental testing found no benefit to developmental outcome. So what can we say? There is no difference between two strategies of permissive hypercapnia with one using a higher and the other a lower threshold for pCO2. It doesn’t however address the issue well of whether targeting a normal pCO2 is better or worse although the authors conclude that it is the short term outcomes of shorter number of days on ventilation that may matter the most.

The Truth is Out There

I want to believe that permissive hypercapnia makes a difference. I have been using the strategy for 15 or so years already and I would like to think it wasn’t poor strategy. I continue to think it makes sense but have to admit that the impact for the average baby is likely not what it once was. Except for the smallest of infants many babies these days born at 27 or more weeks of gestation due to the benefits of antenatal steroids, surfactant and modern ventilation techniques spend few hours to days on the ventilator. Meanwhile the number of factors such chorioamniotitis, early and late onset sepsis and genetic predisposition affect the risks for CLD to a great degree in the modern era. Not that they weren’t at play before but their influence in a period of more gentle ventilation may have a greater impact now. That so many factors contribute to the development of CLD the actual effect of permissive hypercapnia may in fact not be what it once was.

What is not disputed though is that the amount of time on a ventilator when needed is less when the strategy is used. Let us not discount the impact of that benefit as ask any parent if that outcome is of importance to them and you will have your answer.

So has permissive hypercapnia failed to deliver? The answer in terms of the long term outcomes that hospitals use to benchmark against one and other may be yes. The answer from the perspective of the baby and family and at least this Neonatologist is no.

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 15, 2016 | Breastmilk, Uncategorized

Producing milk for your newborn and perhaps even more so when you have had a very preterm infant with all the added stress is not easy. The benefits of human milk have been documented many times over for preterm infants. In a cochrane review from 2014 use of donor human milk instead of formula was associated with a reduction in necrotizing enterocolitis. More recently similar reductions have been seen in retinopathy of prematurity. Interestingly with respect to the latter it would appear that any amount of breast milk leads to a reduction in ROP. Knowing this finding we should celebrate every millilitre of milk that a mother brings to the bedside and support them when it does not flow as easily as they wish. While it would be wonderful for all mothers to supply enough for their infant and even more so that excess could be donated for those who can’t themselves we know this not to be the case. What we can do is minimize stress around the issue by informing parents that every drop counts and to celebrate it as such!

Why Is Breast Milk So Protective

Whether the outcome is necrotizing enterocolitis or ROP the common pathway is one of inflammation. Mother’s own milk contains many anti-inflammatory properties and has been demonstrated to be superior to formula in that regard by Friel and no difference exists between preterm and term versions. Aside from the anti-inflammatory protection there may be other factors at work such as constituents of milk like lactoferrin that may have a protective effect as well although a recent trial would not be supportive of this claim.

Could Mother’s Own Milk Have a Dose Response Effect in Reducing The Risk of BPD?

This is what is being proposed by a study published in early November entitled Influence of own mother’s milk on bronchopulmonary dysplasia and costs. What is special about this study and is the reason I chose to write this post is that the study is unusual in that it didn’t look at the effect of an exclusive human milk diet but rather attempted to isolate the role of mother’s own milk as it pertains to BPD. Patients in this trial were enrolled prospectively in a non randomized fashion with the key difference being the quantity of mothers own milk consumed in terms of a percentage of oral intake. Although donor breast milk existed in this unit, the patients included in this particular cohort only received mother’s own milk versus formula. All told, 254 infants were enrolled in the study. As with many studies looking at risks for BPD the usual culprits were found with male sex being a risk along with smaller and less mature babies and receipt of more fluid in the first 7 days of age. What also came up and turned out after adjusting for other risk factors to be significant as well in terms of contribution was the percentage of mother’s own milk received in the diet.

Every ↑ of 10% = reduction in risk of BPD at 36 weeks PMA by 9.5%

That is a really big effect! Now what about a reduction in costs due to milk? That was difficult to show an independent difference but consider this. Each case of BPD had an additional cost in the US health care system of $41929!

What Lesson Can be Learned Here?

Donor breast milk programs are a very important addition to the toolkit in the NICU. Minimizing the reliance on formula for our infants particularly those below 1500g has reaped many benefits as mentioned above. The availability of such sources though should not deter us from supporting the mothers of these infants in the NICU from striving to produce as much as they can for their infants. Every drop counts! A mother for example who produces only 20% of the needed volume of milk from birth to 36 weeks corrected age may reduce the risk of her baby developing BPD by almost 20%. That number is astounding in terms of effect size. What it also means is that every drop should be celebrated and every mother congratulated for producing what they can. We should encourage more production but rejoice in every 10% milestone.

What it also means in terms of cost is that the provision of lactation consultants in the NICU may be worth their weight in gold. I don’t know what someone performing such services earns in different institutions but if you could avoid two cases of BPD a year in the US I would suspect that nearly $84000 in cost savings would go a long way towards paying for such extra support.

Lastly, it is worth noting that with the NICU environment being as busy as it is sometimes the question “are you planning on breastfeeding?” may be missed. As teams we should not assume that the question was discussed on admission. We need to ask with intention whether a mother is planning on breastfeeding and take the time if the answer is “no” to discuss why it may be worth reconsidering. Results like these are worth the extra effort!

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.

As John F Kennedy discovered when his son Patrick was born at 34 weeks, without such technology available there just wasn’t much that one could do. As premature survival became more and more common and the gestational age at which this was possible younger and younger survivors began to emerge. These survivors had a condition with Northway described in 1967 as classical BPD. This fibrocystic disease which would cripple infants gave way with modern ventilation to the “new bpd”.