In July 2016 I published a blog post No more intubating for meconium? Not quite. In this post I highlighted the recent recommendations to modify the approach to the non vigorous infant born through meconium. The traditional approach of electively intubating such infants for tracheal suctioning before beginning PPV was replaced by provision of PPV first. The rationale here was that delaying the establishment of ventilation while trying to intubate for most situations was more risky than just trying to establish a functional residual capacity (FRC). The naysayers pointed out that while this recommendation is possibly warranted for less experienced intubators, perhaps in the hands of those with more skill, tracheal suctioning would be the better option if it could on average be done quickly.

It has been over two years since that recommendation and change in practice. Isn’t it about time someone looked at whether or not this was a good thing to do?

A Comparison of Two Time Periods

Chiruvolu A et al published Delivery Room Management of Meconium-Stained Newborns and Respiratory Support in this month’s Pediatrics. In this paper the authors compared 4 hospitals with a retrospective period of one year before the NRP changes (October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2016) to a one year prospective period (October 1, 2016, to September 30, 2017) after implementation of the new guidelines. In the retrospective cohort there were 11163 mothers delivered at ≥35 weeks’ gestation. Meconium stained amniotic fluid (MSAF) was present in 1303 (12%) deliveries with 130 (10%) of newborns who were nonvigorous. During the prospective time period, a total of 10 717 mothers delivered at ≥35 weeks’ gestation. MSAF was noted in 1282 (12%) deliveries, yielding 101 (8%) newborns who were nonvigorous. Therefore the study compared these 130 newborns in the retrospective cohort to the 101 in the prospective time period. The authors note that aside from the approach to MSAF there were no changes in care during this time in the delivery room.

A few differences exist though in the cohorts that are worth mentioning that were statistically significant. Firstly, the incidence of preterm and post-term infants were both higher in the prospective cohort (both 6% vs 1%). Secondly, the incidence of fetal distress was higher in the prospective cohort 57% vs 43%. All of these factors would tend to favour the retrospective cohort doing better than the prospective and so the authors in their results controlled for these differences. Not surprisingly the rate of intubation in the retrospective group was 70% vs 2% in the prospective arm.

What were the results?

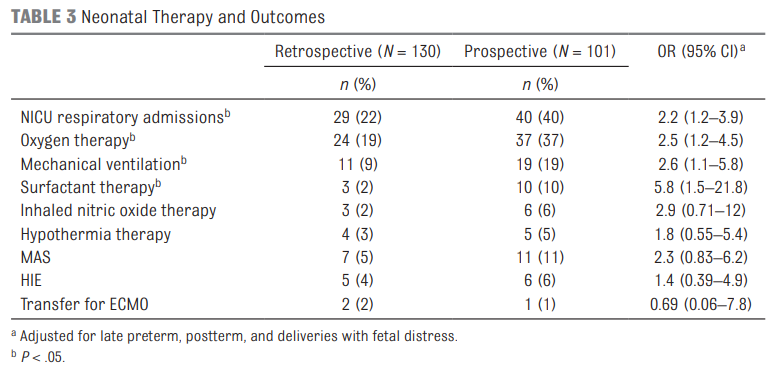

The results shown in table 3 in terms of the Odds ratios have been adjusted for the aforementioned differences of preterm post-term and fetal distress. There are several things here worth noting.  The risk of admission was significantly higher for respiratory distress.

The risk of admission was significantly higher for respiratory distress.

Oxygen needs and mechanical ventilation along with surfactant therapy were also notably higher. One things that showed no difference at all was the mean apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes. This is an interesting finding given the hypothesis that drove the change in practice. If establishing an FRC is the goal of the intervention to provide earlier PPV then shouldn’t the retrospective group have worse apgars due to less effective resuscitation? Maybe or maybe not. This really depends on the staff in the resuscitation room at the 4 hospitals. It might be that the staff were quite skilled so the intubations may have gone smoothly with minimal reductions in FRC compared to the prospective group. What would this study look like if done in a centre with less experienced people capable of intubation.

Oxygen needs and mechanical ventilation along with surfactant therapy were also notably higher. One things that showed no difference at all was the mean apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes. This is an interesting finding given the hypothesis that drove the change in practice. If establishing an FRC is the goal of the intervention to provide earlier PPV then shouldn’t the retrospective group have worse apgars due to less effective resuscitation? Maybe or maybe not. This really depends on the staff in the resuscitation room at the 4 hospitals. It might be that the staff were quite skilled so the intubations may have gone smoothly with minimal reductions in FRC compared to the prospective group. What would this study look like if done in a centre with less experienced people capable of intubation.

Also interesting in this study is that when isolating comparisons to those admitted to the NICU and those specifically diagnosed with MAS there were no differences between groups for such outcomes as length of stay, oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation (MV) or days of MV. Given that the group sizes though were quite small (7 and 11 for MAS) we do have to take this data with a grain of salt as it really is too small to make any certain conclusions. A larger study would need to be done looking at these types of outcomes to really get a better handle on whether the approach to MSAF matters to these individual outcomes.

Final Thoughts

What this study does for me is raise an eyebrow. The change in practice does not seem to yield “better babies”. Secondly what we do see even when controlling for differences that would affect hospital admissions for respiratory distress is an increase in admission rate. In times when beds are becoming increasingly precious as census for many units swell one has to ask whether this approach is truly the better way to go. Perhaps it was wrong for the NRP to declare that for all practitioners it is best to provide PPV rather than intubate. This may have been too simplistic. If you have experienced intubators perhaps it would be best to continue to intubate first in this setting rather than provide PPV. What this study does is certainly raise questions and begs for a larger study to be done to determine whether these results can be replicated. If they are then I suspect the NRP may be headed down a different path for recommendations yet again.

Agree. In the hands of skilled physicians intubation should be done first especially if the airway is clogged with meconium. With a blocked airway PPV may not be effective in achieving FRC.