by All Things Neonatal | Oct 25, 2017 | Neonatal, preemie, Prematurity, ventilation

A patient has been extubated to CPAP and is failing with increasing oxygen requirements or increasing apnea and bradycardia. In most cases an infant would be reintubated but is there another way? While CPAP has been around for some time to support our infants after extubation, a new method using high frequency nasal ventilation has arrived and just doesn’t want to go away. Depending on your viewpoint, maybe it should or maybe it is worth a closer look. I have written about the modality before in High Frequency Nasal Ventilation: What Are We Waiting For? While it remains a promising technology questions still remain as to whether it actually delivers as promised.

Better CO2 elimination?

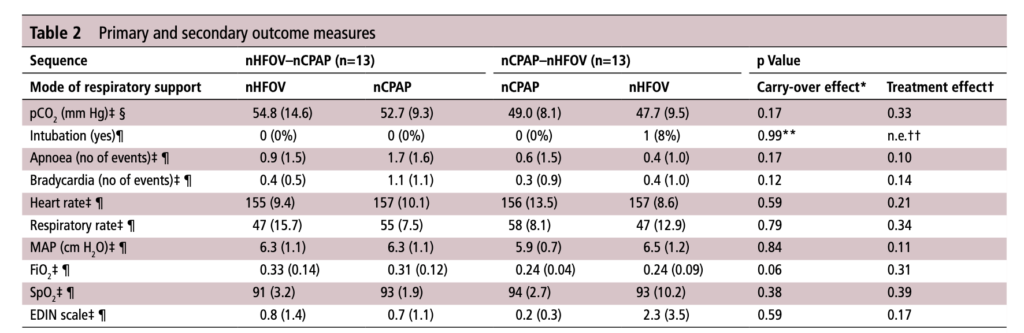

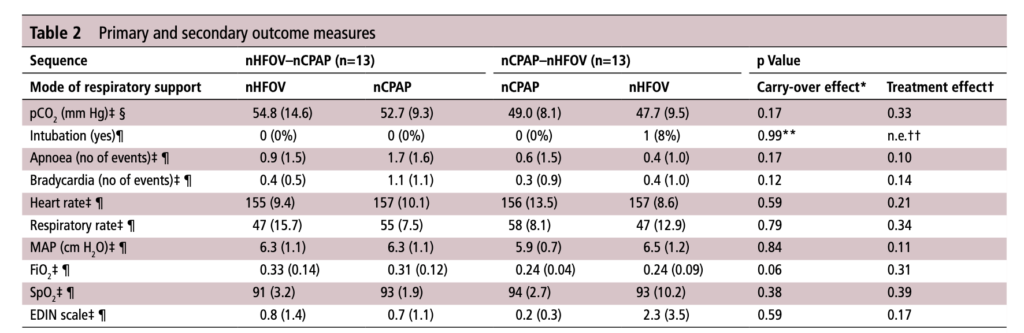

For those who have used a high frequency oscillator, you would know that it does a marvelous job of removing CO2 from the lungs. If it does so well when using an endotracheal tube, why wouldn’t it do just as good a job when used in a non-invasive way? That is the hypothesis that a group of German Neonatologists put forth in their paper this month entitled Non-invasive high-frequency oscillatory ventilation in preterm infants: a randomised controlled crossover trial. In this relatively small study of 26 preterm infants who were all less than 32 weeks at delivery, babies following extubation or less invasive surfactant application were randomized to either receive nHFOV then CPAP for four hours each or the reverse order for the same duration. The primary outcome here was reduction in pCO2 with the goal of seeking a difference of 5% or more in favour of nHFOV. Based on their power calculation they thought they would need 24 infants total and therefore exceeded that number in their enrollment.

The babies in both arms were a bit different which may have confounded the results. The group randomized to CPAP first were larger (mean BW 1083 vs 814g), and there was a much greater proportion of males in the CPAP group. As well, the group randomized first to CPAP had higher baseline O2 saturation of 95% compared to 92% in the nHFOV group. Lastly and perhaps most importantly, there was a much higher rate of capillary blood sampling instead of arterial in the CPAP first group (38% vs 15%). In all cases the numbers are small but when looking for such a small difference in pCO2 and the above mentioned factors tipping the scales one way or the other in terms of illness severity and accuracy of measurement it does give one reason to pause when looking at the results.

The Results

No difference was found in the mean pCO2 from the two groups. As expected, pCO2 obtained from capillary blood gases nearly met significance for being higher than arterial samples (50 vs 47; p=0.052). A similar rate of babies had to drop out of the study (3 on the nCPAP first and 2 on the nHFOV side).

In the end should we really be surprised by the results? I do believe that in the right baby who is about to fail nCPAP a trial of nHFOV may indeed work. By what means I really don’t understand. Is it the fact that the mean airway pressure is generally set higher than on nCPAP in some studies? Could it be the oscillatory vibration being a kind of noxious stimulus that prevents apneic events through irritation of the infant?

While traditional invasive HFOV does a marvelous job of clearing out CO2 I have to wonder how the presence of secretions and a nasopharynx that the oscillatory wave has to avoid (almost like a magic wave that takes a 90 degree turn and then moves down the airway) allows much of any of the wave to reach the distal alveoli. It would be similar to what we know of inhaled steroids being deposited 90 or so percent in the oral cavity and pharynx. There is just a lot of “stuff” in the way from the nostril to the alveolus.

This leads me to my conclusion that if it is pCO2 you are trying to lower, I wouldn’t expect any miracles with nHFOV. Is it totally useless? I don’t think so but for now as a respiratory modality I think for the time being it will continue to be “looking for a place to happen”

by All Things Neonatal | Oct 19, 2017 | BPD, Neonatal, Neonatology, preemie, Prematurity

If you work in Neonatology then chances are you have ordered or assisted with obtaining many chest x-rays in your time. If you look at home many chest x-rays some of our patients get, especially the ones who are with us the longest it can be in the hundreds. I am happy to say the tide though is changing as we move more and more to using other imaging modalities such as ultrasound to replace some instances in which we would have ordered a chest x-ray. This has been covered before on this site a few times; see Point of Care Ultrasound in the NICU, Reducing Radiation Exposure in Neonates: Replacing Radiographs With Bedside Ultrasound. and Point of Care Ultrasound: Changing Practice For The Better in NICU.This post though is about something altogether different.

If you do a test then know what you will do with the result before you order it.

If there is one thing I tend to harp on with students it is to think about every test you do before you order it. If the result is positive how will this help you and if negative what does it tell you as well. In essence the question is how will this change your current management. If you really can’t think of a good answer to that question then perhaps you should spare the infant the poke or radiation exposure depending on what is being investigated. When it comes to the baby born before 30 weeks these infants are the ones with the highest risk of developing chronic lung disease. So many x-rays are done through their course in hospital but usually in response to an event such as an increase in oxygen requirements or a new tube with a position that needs to be identified. This is all reactionary but what if you could do one x-ray and take action based on the result in a prospective fashion?

What an x-ray at 7 days may tell you

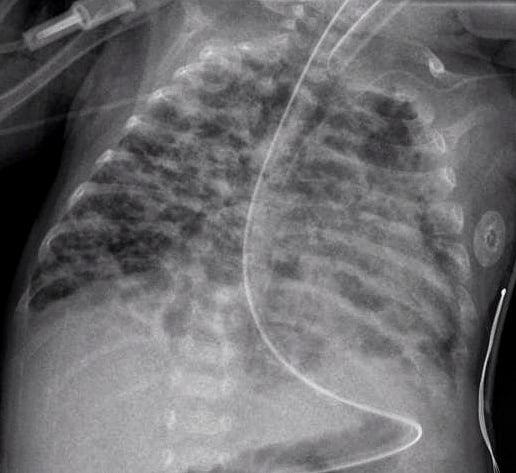

How many times have you caught yourself looking at an x-ray and saying out loud “looks like evolving chronic lung disease”. It turns out that Kim et al in their publication Interstitial pneumonia pattern on day 7 chest radiograph predicts bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants.believe that we can maybe do something proactively with such information.

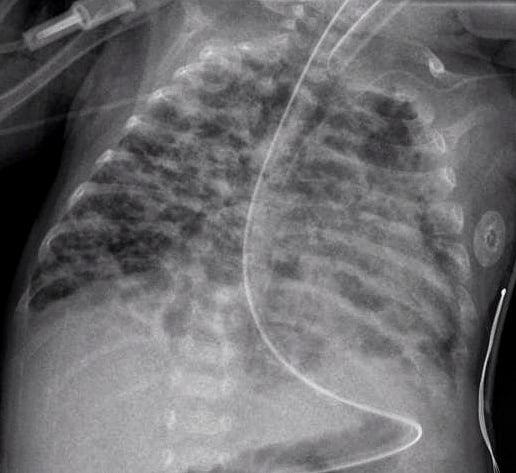

In this study they looked retrospectively at 336 preterm infants weighing less than 1500g and less than 32 weeks at birth. Armed with the knowledge that many infants who have an early abnormal x-ray early in life who go on to develop BPD, this group decided to test the hypothesis that an x-ray demonstrating a pneumonia like pattern at day 7 of life predicts development of BPD.  The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

What do we do with such information?

I suppose the paper tells us something that we have really already known for awhile. Bad lungs early on predict bad lungs at a later date and in particular at 36 weeks giving a diagnosis of BPD. What this study adds if anything is that one can tell quite early whether they are destined to develop this condition or not. The issue then is what to do with such information. The authors suggest that by knowing the x-ray findings this early we can do something about it to perhaps modify the course. What exactly is that though? I guess it is possible that we can use steroids postnatally in this cohort and target such infants as this. I am not sure how far ahead this would get us though as if I had to guess I would say that these are the same infants that more often than not are current recipients of dexamethasone.

Would another dose of surfactant help? The evidence for late surfactant isn’t so hot itself so that isn’t likely to offer much in the way of benefit either.

In the end the truth is I am not sure if knowing concretely that a patient will develop BPD really offers much in the way of options to modify the outcome at this point. Having said that the future may well bring the use of stem cells for the treatment of BPD and that is where I think such information might truly be helpful. Perhaps a screening x-ray at 7 days might help us choose in the future which babies should receive stem cell therapy (should it be proven to work) and which should not. I am proud to say I had a chance to work with a pioneer in this field of research who may one day cure BPD. Dr. Thebaud has written many papers of the subject and if you are looking for recent review here is one Stem cell biology and regenerative medicine for neonatal lung diseases.Do I think that this one paper is going to help us eradicate BPD? I do not but one day this strategy in combination with work such as Dr. Thebaud is doing may lead us to talk about BPD at some point using phrases like “remember when we used to see bad BPD”. One can only hope.

by All Things Neonatal | Oct 5, 2017 | Innovation, Neonatology, ventilation

It has been over two years since I have written on this subject and it continues to be something that I get excited about whenever a publication comes my way on the topic. The last time I looked at this topic it was after the publication of a randomized trial comparing in which one arm was provided automated FiO2 adjustments while on ventilatory support and the other by manual change. Automated adjustments of FiO2. Ready for prime time? In this post I concluded that the technology was promising but like many new strategies needed to be proven in the real world. The study that the post was based on examined a 24 hour period and while the results were indeed impressive it left one wondering whether longer periods of use would demonstrate the same results. Moreover, one also has to be wary of the Hawthorne Effect whereby the results during a study may be improved simply by being part of a study.

The Real World Demonstration

So the same group decided to look at this again but in this case did a before and after comparison. The study looked at a group of preterm infants under 30 weeks gestational age born from May – August 2015 and compared them to August to January 2016. The change in practice with the implementation of the CLiO2 system with the Avea ventilator occurred in August which allowed two groups to be looked at over a relatively short period of time with staff that would have seen little change before and after. The study in question is by Van Zanten HA The effect of implementing an automated oxygen control on oxygen saturation in preterm infants. For the study the target range of FiO2 for both time periods was 90 – 95% and the primary outcome was the percentage of time spent in this range. Secondary outcomes included time with FiO2 at > 95% (Hyperoxemia) and < 90, <85 and < 80% (hypoxemia). Data were collected when infants received respiratory support by the AVEA and onlyincluded for analysis when supplemental oxygen was given, until the infants reached a GA of 32 weeks

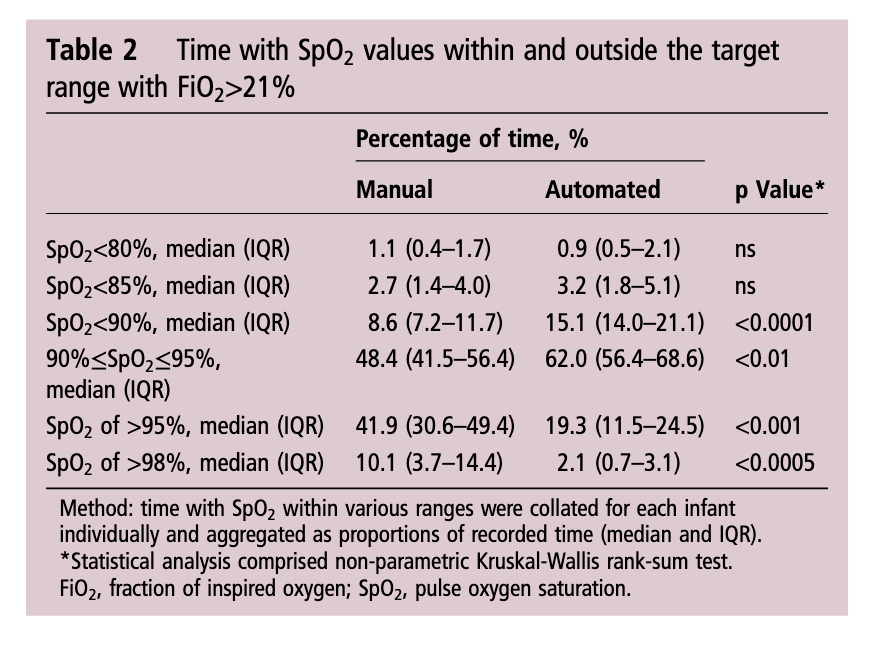

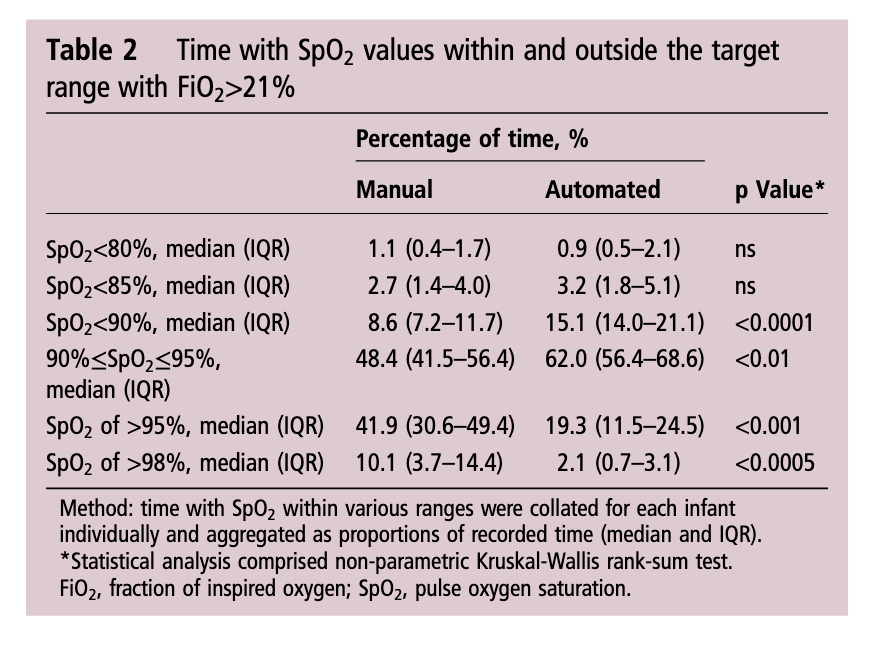

As you might expect since a computer was controlling the FiO2 using a feedback loop from the saturation monitor it would be a little more accurate and immediate in manipulating FiO2 than a bedside nurse who has many other tasks to manage during the care of an infant. As such the median saturation was right in the middle of the range at 93% when automated and 94% when manual control was used. Not much difference there but as was seen in the shorter 24 hour study, the distribution around the median was tighter with automation. Specifically with respect to ranges, hyperoxemia and hypoxemia the following was noted (first number is manual and second comparison automated in each case).

Time spent in target range: 48.4 (41.5–56.4)% vs 61.9 (48.5–72.3)%; p<0.01

Hyperoxemia >95%: 41.9 (30.6–49.4)% vs 19.3 (11.5–24.5)%; p<0.001

< 90%: 8.6 (7.2–11.7)% vs 15.1 (14.0–21.1)%;p<0.0001

< 85%: 2.7 (1.4–4.0)% vs 3.2 (1.8–5.1)%; ns

Hypoxemia < 80%: 1.1 (0.4–1.7)% vs 0.9 (0.5–2.1)%; ns

What does it all mean?

I find it quite interesting that while hyperoxemia is reduced, the incidence of saturations under 90% is increased with automation. I suspect the answer to this lies in the algorithmic control of the FiO2. With manual control the person at the bedside may turn up a patient (and leave them there a little while) who in particular has quite labile saturations which might explain the tendency towards higher oxygen saturations. This would have the effect of shifting the curve upwards and likely explains in part why the oxygen saturation median is slightly higher with manual control. With the algorithm in the CLiO2 there is likely a tendency to respond more gradually to changes in oxygen saturation so as not to overshoot and hyperoxygenate the patient. For a patient with labile oxygen saturations this would have a similar effect on the bottom end of the range such that patients might be expected to drift a little lower then the target of 90% as the automation corrects for the downward trend. This is supported by the fact that when you look at what is causing the increase in percentage of time below 90% it really is the category of 85-89%.

Is this safe? There will no doubt be people reading this that see the last line and immediately have flashbacks to the SUPPORT trial which created a great deal of stress in the scientific community when the patients in the 85-89% arm of the trial experienced higher than expected mortality. It remains unclear what the cause of this increased mortality was and in truth in our own unit we accept 88 – 92% as an acceptable range. I have no doubt there are units that in an attempt to lessen the rate of ROP may allow saturations to drop as low as 85% so I continue to think this strategy of using automation is a viable one.

For now the issue is one of a ventilator that is capable of doing this. If not for the ventilated patient at least for patients on CPAP. In our centre we don’t use the Avea model so that system is out. With the system we use for ventilation there is also no option. We are anxiously awaiting the availability of an automated system for our CPAP device. I hope to be able to share our own experience positively when that comes to the market. From my standpoint there is enough to do at the bedside. Having a reliable system to control the FiO2 and minimize oxidative stress is something that may make a real difference for the babies we care for and is something I am eager to see.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.

The patterns they were looking at are demonstrated in this figure from the paper. Essentially what the authors noted was that having the worst pattern of the lot predicted the development of later BPD. The odds ratio was 4.0 with a confidence interval of 1.1 – 14.4 for this marker of BPD. Moreover, birthweight below 1000g, gestational age < 28 weeks and need for invasive ventilation at 7 days were also linked to the development of the interstitial pneumonia pattern.