by All Things Neonatal | Dec 21, 2016 | nutrition, preemie, Prematurity

A strange title perhaps but not when you consider that both are in much need of increasing muscle mass. Muscle takes protein to build and a global market exists in the adult world to achieve this goal. For the preterm infant human milk fortifiers provide added protein and when the amounts remain suboptimal there are either powdered or liquid protein fortifiers that can be added to the strategy to achieve growth. When it comes to the preterm infant we rely on nutritional science to guide us. How much is enough? The European Society For Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition published recommendations in 2010 based on consensus and concluded:

“We therefore recommend aiming at 4.0 to 4.5 g/kg/day protein intake for infants up to 1000 g, and 3.5 to 4.0 g/kg/day for infants from 1000 to 1800 g that will meet the needs of most preterm infants. Protein intake can be reduced towards discharge if the infant’s growth pattern allows for this. The recommended range of protein intake is therefore 3.5 to 4.5 g/kg/day.”

These recommendations are from six years ago though and are based on evidence that preceded their working group so one would hope that the evidence still supports such practice. It may not be as concrete though as one would hope.

Let’s Jump To 2012

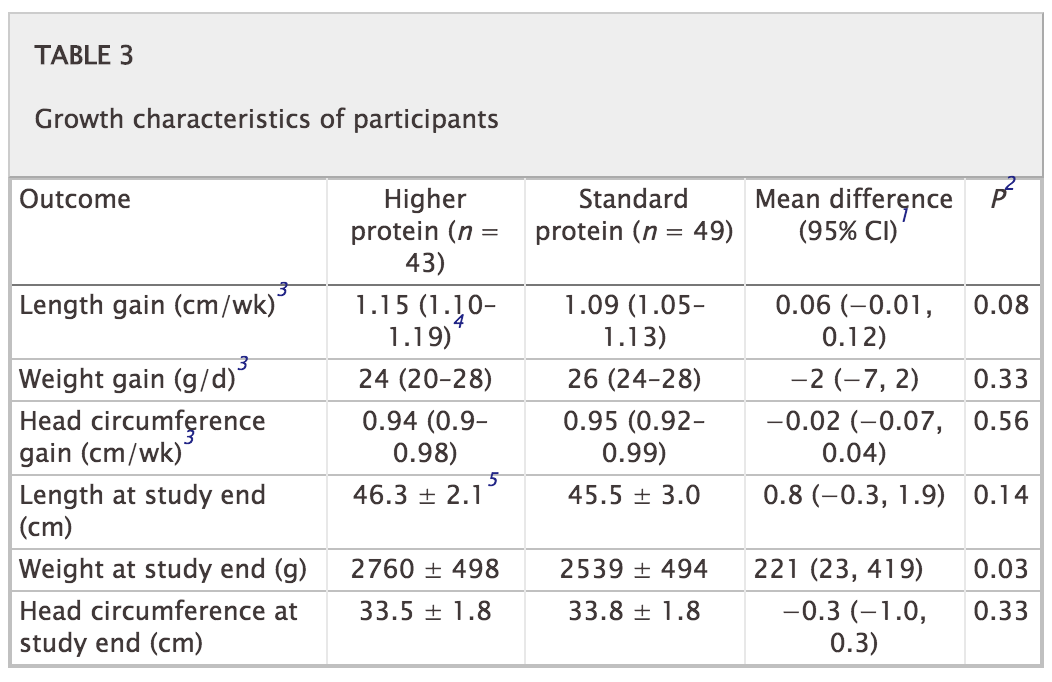

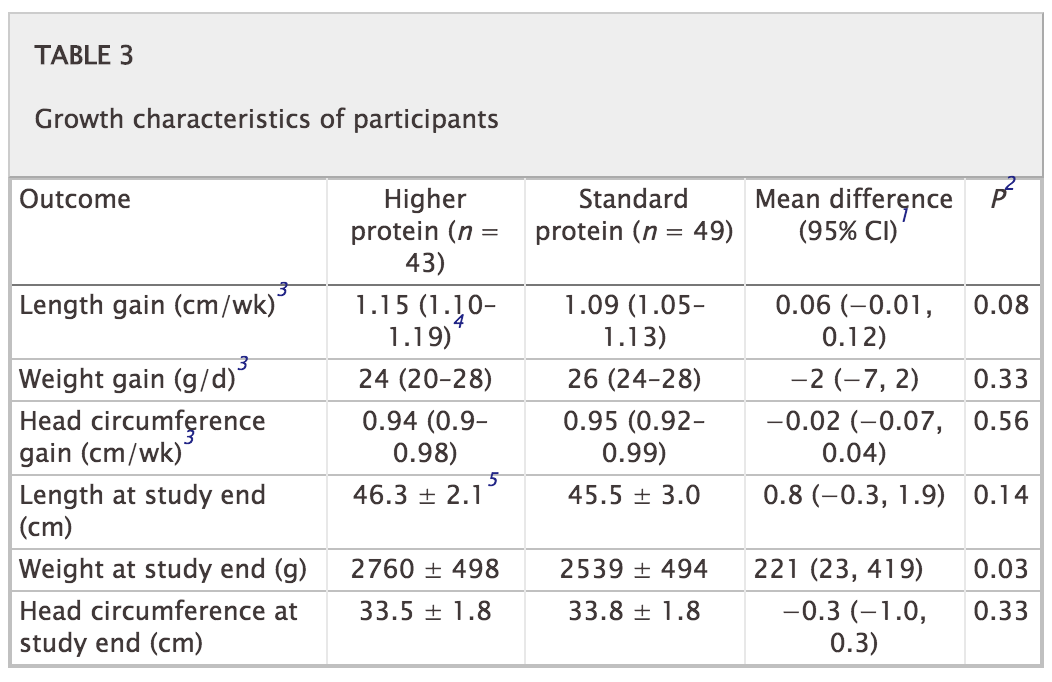

Miller et al published an RCT on the subject entitled Effect of increasing protein content of human milk fortifier on growth in preterm infants born at <31 wk gestation: a randomized controlled trial. This trial is quite relevant in that it involved 92 infants (mean GA 27-28 weeks and about 1000g on average at the start), 43 of whom received a standard amount of protein 3.6 g/kg/day vs 4.2 g/kg/d in the high protein group. This was commenced once fortification was started and carried through till discharge with energy intakes and volume of feeds being the same in both groups. The authors used a milk analyzer to ensure consistency in the total content of nutrition given the known variability in human milk nutritional content. The results didn’t show much to write home about. There were no differences in weight gain or any measurements but the weight at discharge was a little higher in the high protein group. The length of stay trended towards a higher number of days in the high protein group so that may account for some of the difference. All in all though 3.6 or 4.2 g/kg/d of protein didn’t seem to do much to enhance growth.

Now let’s jump to 2016

This past month Maas C et al published an interesting trial on protein supplementation entitled Effect of Increased Enteral Protein Intake on Growth in Human Milk-Fed Preterm Infants: A Randomized Clinical Trial. This modern day study had an interesting question to answer. How would growth compare if infants who were fed human milk were supplemented with one of three protein contents based on current recommendations. The first group of 30 infants all < 32 weeks received standard protein intake of 3.5 g/kg/d while the second group of 30 were given an average intake of 4.1 g/kg/d. The second group of 30 were divided though into an empiric group in which the protein content of maternal or donor milk was assumed to be a standard amount while the second 15 had their protein additive customized based on an analysis of the human milk being provided. Whether the higher intake group was estimated or customized resulted in no difference in protein intake on average although variability between infants in actual intake was reduced. Importantly, energy intake was no different between the high and low groups so if any difference in growth was found it would presumably be related to the added protein.

Does it make a difference?

The results of this study failed to show any benefit to head circumference, length or weight between the two groups. The authors in their discussion postulate that there is a ceiling effect when it comes to protein and I would tend to agree. There is no question that if one removes protein from the diet an infant cannot grow as they would begin to break down muscle to survive. At some point the minimum threshold is met and as one increases protein and energy intake desired growth rates ensue. What this study suggests though is that there comes a point where more protein does not equal more growth. It is possible to increase energy intakes further as well but then we run the risk of increasing adiposity in these patients.

I suppose it would be a good time to express what I am not saying! Protein is needed for the growing preterm infant so I am not jumping on the bandwagon of suggesting that we should question the use of protein fortification. I believe though that the “ceiling” for protein use lies somewhere between 3.5 – 4 g/kg/d of protein intake. We don’t really know if it is at 3.5, 3.7, 3.8 or 3.9 but it likely is sitting somewhere in those numbers. It seems reasonable to me to aim for this range but follow urea (something outside of renal failure I have personally not paid much attention to). If the urea begins rising at a higher protein intake approaching 4 g/kg/d perhaps that is the bodies way of saying enough!

Lastly this study also raises a question in my mind about the utility of milk analyzers. At least for protein content knowing precisely how much is in breastmilk may not be that important in the end. Then again that raises the whole question of the accuracy of such devices but I imagine that could be the source of a post for another day.

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 15, 2016 | Breastmilk, Uncategorized

Producing milk for your newborn and perhaps even more so when you have had a very preterm infant with all the added stress is not easy. The benefits of human milk have been documented many times over for preterm infants. In a cochrane review from 2014 use of donor human milk instead of formula was associated with a reduction in necrotizing enterocolitis. More recently similar reductions have been seen in retinopathy of prematurity. Interestingly with respect to the latter it would appear that any amount of breast milk leads to a reduction in ROP. Knowing this finding we should celebrate every millilitre of milk that a mother brings to the bedside and support them when it does not flow as easily as they wish. While it would be wonderful for all mothers to supply enough for their infant and even more so that excess could be donated for those who can’t themselves we know this not to be the case. What we can do is minimize stress around the issue by informing parents that every drop counts and to celebrate it as such!

Why Is Breast Milk So Protective

Whether the outcome is necrotizing enterocolitis or ROP the common pathway is one of inflammation. Mother’s own milk contains many anti-inflammatory properties and has been demonstrated to be superior to formula in that regard by Friel and no difference exists between preterm and term versions. Aside from the anti-inflammatory protection there may be other factors at work such as constituents of milk like lactoferrin that may have a protective effect as well although a recent trial would not be supportive of this claim.

Could Mother’s Own Milk Have a Dose Response Effect in Reducing The Risk of BPD?

This is what is being proposed by a study published in early November entitled Influence of own mother’s milk on bronchopulmonary dysplasia and costs. What is special about this study and is the reason I chose to write this post is that the study is unusual in that it didn’t look at the effect of an exclusive human milk diet but rather attempted to isolate the role of mother’s own milk as it pertains to BPD. Patients in this trial were enrolled prospectively in a non randomized fashion with the key difference being the quantity of mothers own milk consumed in terms of a percentage of oral intake. Although donor breast milk existed in this unit, the patients included in this particular cohort only received mother’s own milk versus formula. All told, 254 infants were enrolled in the study. As with many studies looking at risks for BPD the usual culprits were found with male sex being a risk along with smaller and less mature babies and receipt of more fluid in the first 7 days of age. What also came up and turned out after adjusting for other risk factors to be significant as well in terms of contribution was the percentage of mother’s own milk received in the diet.

Every ↑ of 10% = reduction in risk of BPD at 36 weeks PMA by 9.5%

That is a really big effect! Now what about a reduction in costs due to milk? That was difficult to show an independent difference but consider this. Each case of BPD had an additional cost in the US health care system of $41929!

What Lesson Can be Learned Here?

Donor breast milk programs are a very important addition to the toolkit in the NICU. Minimizing the reliance on formula for our infants particularly those below 1500g has reaped many benefits as mentioned above. The availability of such sources though should not deter us from supporting the mothers of these infants in the NICU from striving to produce as much as they can for their infants. Every drop counts! A mother for example who produces only 20% of the needed volume of milk from birth to 36 weeks corrected age may reduce the risk of her baby developing BPD by almost 20%. That number is astounding in terms of effect size. What it also means is that every drop should be celebrated and every mother congratulated for producing what they can. We should encourage more production but rejoice in every 10% milestone.

What it also means in terms of cost is that the provision of lactation consultants in the NICU may be worth their weight in gold. I don’t know what someone performing such services earns in different institutions but if you could avoid two cases of BPD a year in the US I would suspect that nearly $84000 in cost savings would go a long way towards paying for such extra support.

Lastly, it is worth noting that with the NICU environment being as busy as it is sometimes the question “are you planning on breastfeeding?” may be missed. As teams we should not assume that the question was discussed on admission. We need to ask with intention whether a mother is planning on breastfeeding and take the time if the answer is “no” to discuss why it may be worth reconsidering. Results like these are worth the extra effort!

by All Things Neonatal | Dec 7, 2016 | Neonatal, Neonatology, newborn, Uncategorized

Throughout my career one thing has been consistently true. That is that wherever I was working and regardless of the role I have been an educator. I imagine the blog to a great extent is related to my interest in this aspect of my work. In the last few years much has been said about care by parents whether it be a general approach for family centred care or in formalized approaches such as FiCare which has also been formally studied in the research setting. When we speak of family centred care, one thing that I am constantly reminded of is that the focus of all of our efforts must be on the family and the patient. As I said recently to a colleague when discussing what was presented as a difficult discussion with another colleague due to a disagreement about the direction of management, when you put the patient first the discussion really isn’t difficult at all. It’s not about you or a colleagues ego but about the patient and if the management is not up to par then change direction and worry about managing egos later.

What We Know And What They Know

Another aspect that needs to be addressed is the difference in power that we have through knowledge. I am not talking about us exerting authority over families but from the perspective of us having the knowledge from years of experience in the field as to what is significant and what is not in terms of events in the NICU. The evidence for example with respect to neurodevelopmental outcome from apnea and bradycardia should give us reason to be optimistic the majority of the time. While in Edmonton I learned a great deal from one of my colleagues who was the lead author in a paper entitled Early childhood neurodevelopment in very low birth weight infants with predischarge apnea. While frequent apnea may be associated with mild motor impairments in their paper, the predictive value of these predischarge recordings is very limited when you take away those kids without severe IVH. I think about all of the parents we see who have their eyes glued to the monitors while they attend at the bedside and what they must be thinking. To us it is just a matter of time but I wonder for them how agonizing a time it really is! It isn’t just those infants who are nearing discharge and having apnea either as the CAP study at 5 years of age showed no difference in survival without disability in those infants who received caffeine vs those who did not. More frequent events may not be that detrimental after all. I am not suggesting we not treat patients as one never knows where the threshold lies to cause injury but these preemies are certainly made of some tough stuff.

Identifying Stress and Preparing Parents For it

The first step in dealing with this issue is to know it is there. Recognizing this, Melnyk and others performed an educational intervention targeting behaviour of families in their study Reducing premature infants’ length of stay and improving parents’ mental health outcomes with the Creating Opportunities for Parent Empowerment (COPE) neonatal intensive care unit program: a randomized, controlled trial. The group of parents who went through the program had better mental health outcomes compared to the control groups. The issue here and really is at the crux of the goal in writing all of this is that the stress that parents feel may not be overtly present. The squeaky wheel as the saying goes gets the grease and the parents that are demonstrating signs of poor coping are the first to draw the referrals to social work or engage in a deeper conversation with nursing at the bedside. All parents experience stress at least to a certain degree and it is all of our jobs to tease it out. On the other hand employing standardized approaches such as the COPE program for all parents might be another way of helping those who are in need but not clearly wearing a sign on their foreheads that say “help me”.

Don’t Underestimate the Power of Reassurance

So we know that much of what we see on the monitors will not lead to long term harm, transient central cyanosis during feeds will not damage the brain and apnea of prematurity is a distinct entity from SIDS. The parents on the other hand commonly make these links and additionally in case no one has mentioned it to you, those babies with TTN may one day develop asthma and those with hypoglycemia may have diabetes (we know both not to be true but I have been asked about this many times). This is why I believe it is our duty to explain why we are not worried about things that come up in the unit. Saying “don’t worry” or “that is normal preterm behaviour” may not be enough. Ask a parent what it is they are worried about and you may be surprised to find out the links that they have made in their heads, some of which may be valid but some completely false. I am not meaning to trivialize their concerns but rather validate them as real worries. If we have the knowledge and it is power as I said before then shouldn’t we use that power to help reduce their stress?

So we know that much of what we see on the monitors will not lead to long term harm, transient central cyanosis during feeds will not damage the brain and apnea of prematurity is a distinct entity from SIDS. The parents on the other hand commonly make these links and additionally in case no one has mentioned it to you, those babies with TTN may one day develop asthma and those with hypoglycemia may have diabetes (we know both not to be true but I have been asked about this many times). This is why I believe it is our duty to explain why we are not worried about things that come up in the unit. Saying “don’t worry” or “that is normal preterm behaviour” may not be enough. Ask a parent what it is they are worried about and you may be surprised to find out the links that they have made in their heads, some of which may be valid but some completely false. I am not meaning to trivialize their concerns but rather validate them as real worries. If we have the knowledge and it is power as I said before then shouldn’t we use that power to help reduce their stress?

Engaging Families Can Reap Huge Dividends

The movement towards family centred care and more specifically care by parent will have a dramatic impact on this issue. As more and more centres move to engaging families to be part of rounds and not just listen and then ask questions but to take some degree of control and provide some of the reporting stress will be reduced. It is only logical. The more a family comes to understand what is significant and what is not in terms of reporting concerns the more confident they will be. Moreover, spending more time at the bedside leads to more skin to skin care and with that shorter hospital stays due to better cardiorespiratory stability. We aren’t there yet but we are headed in the right direction. In the meantime, take the time to ask a simple question “what are you worried about” to parents no matter how confident and strong they appear and you may find yourself with an opportunity to harness the power of education you have a make a real difference to a family in need.

So we know that much of what we see on the monitors will not lead to long term harm, transient central cyanosis during feeds will not damage the brain and apnea of prematurity is a distinct entity from SIDS. The parents on the other hand commonly make these links and additionally in case no one has mentioned it to you, those babies with TTN may one day develop asthma and those with hypoglycemia may have diabetes (we know both not to be true but I have been asked about this many times). This is why I believe it is our duty to explain why we are not worried about things that come up in the unit. Saying “don’t worry” or “that is normal preterm behaviour” may not be enough. Ask a parent what it is they are worried about and you may be surprised to find out the links that they have made in their heads, some of which may be valid but some completely false. I am not meaning to trivialize their concerns but rather validate them as real worries. If we have the knowledge and it is power as I said before then shouldn’t we use that power to help reduce their stress?

So we know that much of what we see on the monitors will not lead to long term harm, transient central cyanosis during feeds will not damage the brain and apnea of prematurity is a distinct entity from SIDS. The parents on the other hand commonly make these links and additionally in case no one has mentioned it to you, those babies with TTN may one day develop asthma and those with hypoglycemia may have diabetes (we know both not to be true but I have been asked about this many times). This is why I believe it is our duty to explain why we are not worried about things that come up in the unit. Saying “don’t worry” or “that is normal preterm behaviour” may not be enough. Ask a parent what it is they are worried about and you may be surprised to find out the links that they have made in their heads, some of which may be valid but some completely false. I am not meaning to trivialize their concerns but rather validate them as real worries. If we have the knowledge and it is power as I said before then shouldn’t we use that power to help reduce their stress?